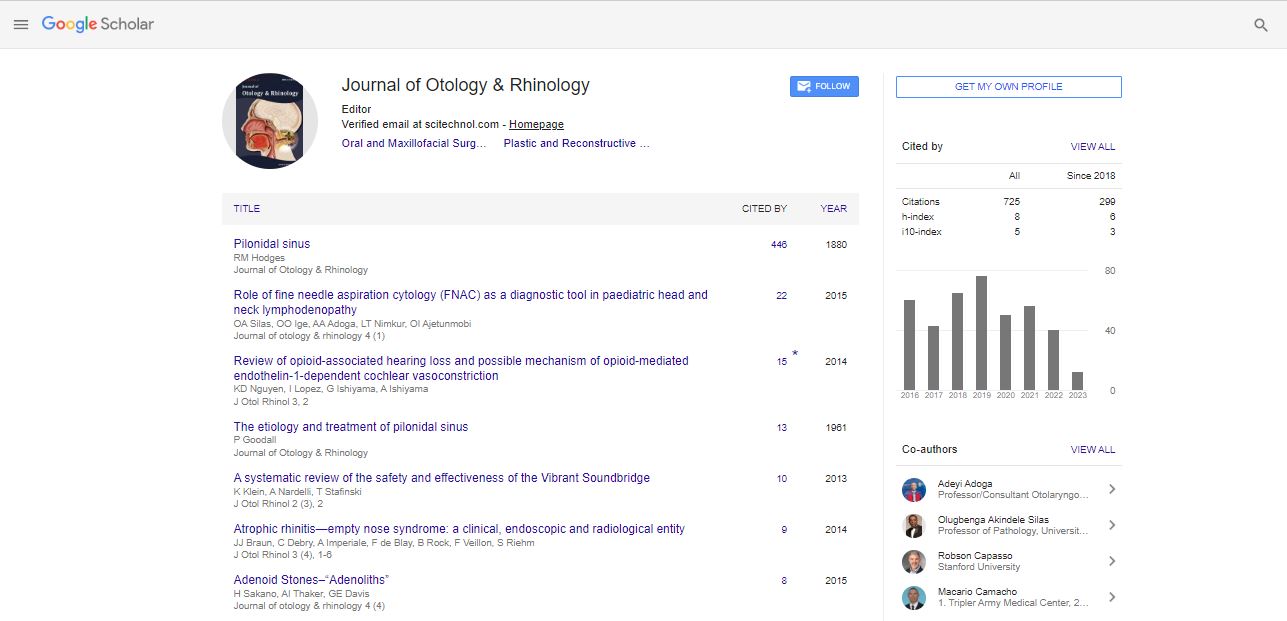

Research Article, J Otol Rhinol Vol: 5 Issue: 5

Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD): A systematic review of 10 years’ progress in diagnosis and treatment

| Honorata Crisan1*, Nadia des Courtis2 and Antoine des Courtis3 | |

| 1Clinique la Prairie, Ear nose throat practice, Montreux, Switzerland | |

| 2Cabinet des Eaux Vives, Psychiatry practice, Geneva, Switzerland | |

| 3Department of Oto-rhino-laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland | |

| Corresponding author : Honorata Crisan

Clinique la Prairie, Ear nose throat practice, Montreux, Switzerland Tel: +41 76 540 6401 Fax: +20552334959 E-mail: honorata_crisan@yahoo.com |

|

| Received: September 21, 2016 Accepted: October 03, 2016 Published: October 11, 2016 | |

| Citation: Crisan H, Courtis N, Courtis A (2016) Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD): A Systematic Review of 10 Years��? Progress in Diagnosis and Treatment. J Otol Rhinol 5:5. doi:10.4172/2324-8785.1000290 |

Abstract

Objective: We reviewed the existing literature on Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) and enquired about symptoms, diagnosis and treatments proposed in order to assess how concepts, diagnostic criteria and treatment have evolved over the last 10 years.

Method: We conducted a systematic review of the literature.

Results: PPPD is a frequent entity that has been only recently well described. Diagnosis relies on anamnesis; posturography is helpful. High scores of depression, neuroticism and introversion may be a risk factor for PPPD. 25% of cases may be triggered by neurotologic events such as Vestibular migraine, which is more prevalent than Meniere’s disease. There are alterations in activity and connectivity in the key central vestibular, visual and anxiety systems. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and especially Sertraline could be the medication of choice. Other SSRI or Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) may be chosen in case of comorbid psychiatric disorders or insufficient response to the first choice medication. Cognitive behavioural therapy, vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy seem to be effective.

Conclusion: PPPD seems to stem from a multi-sensory maladjustment. Symptoms of Vestibular migraine, Meniere’s disease and PPPD are often overlapping, stressing the need for more precise diagnostic tools. Cognitive behavioural therapy and vestibular rehabilitation therapy have been recently proved to be effective therapeutic options for PPPD. However, there is little progress done concerning drug-treatments: SSRI and SNRI may help, but there is a need for larger controlled double-blind trials to confirm the effectiveness.

Keywords: Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness; Anxiety; Neuroticism; Introversion selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI); Multisensory maladjustment; Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT); Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy (VBRT)

Keywords |

| Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness; Anxiety; Neuroticism |

Abbreviations |

| VBRT: Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy; CBT: Cognitive behavioural therapy, PPPD: Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness; CSD: Chronic Subjective Dizziness; DHI: Dizziness Handicap Inventory; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; NEO-PI-R: Personality Inventory-Revised MD: Meniere’s Disease; VM: Vestibular Migraine; PPV: Phobic Postural Vertigo; PIVC: Parieto-insular Vestibular Cortex; BSI-53: Brief Symptom Inventory-53; SNRI: Serotonin and Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor; SSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors |

Introduction |

| The first descriptions of phobic postural vertigo (PPV) were done by Brandt T. and Dieterich M. in 1986. At that time the diagnosis of PPV was rarely considered despite its frequent prevalence in neurotologic practice. Later on Staab and Ruckenstein [1,2] initiated a series of studies in order to refine and update the former concept of PPV calling it Chronic Subjective Dizziness (CSD). In 2013 it was renamed Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD). PPPD is defined as a neurotologic disorder of non-vertiginous dizziness or unsteadiness over at least a 3 months’ period that is persistent throughout the day [3]. It is a frequent condition observed in neurotologic practice. It can be the second most common diagnosis among patients with vestibular symptoms in tertiary neurotology centers [3]. The symptoms can be aggravated by upright posture (i.e. walking, standing). Provocative factors are the patients’ own movements (active or passive), exposure to large-field moving visual stimuli (shopping malls, cinema) or performing precise visual tasks (using computer, fine tasks with hands). Best et al. [4] stated that PPPD may develop in about 25% of patients after a neurotologic incident, such as vestibular neuritis, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere’s disease (MD), vestibular migraine (VM) or any other event causing acute attacks of vertigo (e.g. traumatic brain injury, panic attack, dysrhythmia, adverse drug reaction etc.). Behavioural factors like anxiety, introvert personality and depression are believed to predispose to developing PPPD [5,6]. Finally, the World Health Organization has included PPPD in its draft list of diagnoses to be added to the next edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) in 2017. |

| We reviewed systematically the articles concerning the issue of PPPD (CSD) since its first official description by Staab and Ruckenstein [1,2] in 2007, We enquired about symptoms, diagnosis and treatments proposed in order to assess the progress that has been achieved over the last 10 years. |

Materials and Methods |

| We performed a systematic review of the literature based on articles referenced in Pubmed and Google Scholar, focusing on diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment of PPPD. We used the following key words: “Chronic subjective dizziness” “CSD”; “Persistent Postural- Perceptual Dizziness” “PPPD”. We reviewed all papers, published in English between 2000 and 2016. We excluded all case reports and all non-English language articles. To avoid confusion, in our review we replaced the former name of Chronic Subjective Dizziness (CSD) by the actual Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD). |

Results of the Literature Review |

| Pathophysiology and diagnosis |

| Among the 15 articles matching our criteria, we excluded 4 case reports and 1 non-English language study and hence analysed 10 original papers. Anxiety disorders predict the development of PPPD symptoms after an acute neurotologic disease [4-7]. Staab et al. [8] focused on personality traits that might be associated with the development of PPPD. They conducted a prospective study concerning patients with either PPPD (n=24) or chronic neurotologic conditions and anxiety disorders (control group; n=16). Four different diagnostic tools were used to measure the levels of anxiety, depressive disorders and personality traits (Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMIV) and Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-PI-R). The depression score was significantly higher in the PPPD group. Patients with PPPD were also significantly more introvert and anxious with lower scores of trust than those in the control group. A high score of neuroticism and introversion seem to be risk factors for PPPD as it seems to be the case for other functional syndromes like irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia and non-cardiac chest pain. Conscientious traits of personality were not associated with PPPD and this finding excludes the obsessive-compulsive personality as a risk factor for developing PPPD. |

| A study by Neff et al. [9] has compared the prevalence of PPPD in MD and VM patients. He found that 91% of PPPD patients were in the VM group. These findings confirmed the observations by Best et al. [4]. |

| Autonomic dizziness may often mimic PPPD [10] and an autonomic dysfunction may provoke persistent dizziness even in the absence of syncopal symptoms. The authors proposed an updated autonomic testing protocol, by measuring head upright tilt, CO2 inhalation and hyperventilation test. As the study was based on 12 subjects without control group, statistical analysis was impossible. |

| Feuerecker et al. [11] performed a prospective study comparing the intensity of diurnal symptoms of patients with PPPD (n=131), bilateral vestibulopathy (n=108) and downbeat nystagmus (n=38). The study showed that patients presenting PPPD had less or no symptoms after getting up in the morning. This finding might be a diagnostic hint for PPPD. |

| A study by Ödman et al. [12] focused on testing the balance function in patients with PPPD. They performed Mumedia’s Statitest dynamic posturography in 105 patients with PPPD: 79% of the patients showed a poor balance performance, 88% had a disturbed balance field and in 58% of the cases an altered sensory organization of balance was observed. Sohsten et al. [13] confirmed their findings, testing, by posturography, 3 groups of patients (PPPD, patients recovered after acute vestibular syndrome and group of healthy individuals). |

| Schniepp et al. [14] examined gait control in PPPD and observed a significant inadequate, cautious gait control, indicating a higher reliance of patients on visual information while walking compared to the control group. |

| Holle et al. [15] investigated whether other sensory inputs such as pain stimuli might be altered, knowing that most of the PPPD patients suffer central perception dysfunction. The nociceptive blink reflex was measured in 27 patients with PPPD versus 27 healthy, age and gender-matched controls. They noted a significant reduction in habituation of this reflex in PPPD patients compared to healthy ones. |

| An article by Indovina et al [16] focused on alterations in activity and connectivity in the insula and hippocampus where the vestibular- and anxiety-related processes overlap in the brain. They hypothesized that these alterations in response to vestibular stimulimay be the neural basis of PPPD. The brain activity was examined via functional magnetic resonance imaging during loud short tone bursts stimulus. 18 patients diagnosed with PPPD and 18 healthy controls were compared. A reduction of activity was observed in key regions of the vestibular, visual and anxiety systems in the PPPD patients group. They observed reduced activation of posterior and anterior insula and adjacent frontal operculum, in the inferior frontal gyrus, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex and in the parieto-insular vestibular cortex (PIVC). Connectivity changes among these regions were also noticed. All this may result in abnormal sensations of selfmotion, visually induced dizziness and anxiety. |

| Treatment |

| Among the 10 original papers found, we excluded 1 non-English language study. |

| One of the first medication trials for patients with PPPD was performed in 2004 [17]. This prospective trial focused on Sertraline as a treatment for PPPD. 24 patients were treated with titrated doses between 25 and 200 mg per day to reach the optimal benefit. The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) and Brief Symptom Inventory-53 (BSI-53) were used to evaluate the efficacy of this treatment. 75% of the patients completed the treatment. In this study, Sertraline significantly reduced the scores by week 8 on both DHI and BSI-53 scales. However Sertraline was not compared to placebo or other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). Furthermore, this study was supported by an unrestricted grant from a major pharmaceutical company. A former study of Staab et al. [18] investigated the efficacy of a group of SSRI medications for patients with dizziness and major or minor psychiatric symptoms with or without neurotologic illnesses. The concept of PPPD was not specified by that time. This retrospective non-blinded study without control group was the first investigation of SSRI treatment efficacy for patients with dizziness. Sertraline was available in the lowest-dosage tablets comparing to other SSRI, so it was prescribed most frequently (n=40). The others were prescribed less often: fluoxetine (n=11), paroxetine (n=13), and citalopram (n=5). Despite the high rates of adverse effects (25%), 84% of patients, who completed the treatment, improved. There was no difference in the response between the patients presenting less psychiatric symptoms and those with major psychiatric disorders. Patients with only psychiatric disorder and those with coexisting peripheral vestibular conditions or migraine headaches improved better than patients with central nervous system deficits. In this study, the efficacy of each molecule was not assessed separately. |

| Later on, Staab and Ruckenstein [19] studied the longitudinal pattern of patients’ symptoms and the efficacy of SSRI treatment. They concluded that PPPD patients with clinically significant anxiety, prior to neurotologic illness, might require more intensive treatment compared to patients with primary neurotologic conditions and consecutive anxiety disorders or patients with anxiety disorders only. |

| Horii et al. [20] studied the effects of Fluvoxamine and found that patients with or without physical neurotologic deficits, that reported chronic dizziness accompanied by anxiety and depression (as measured by HADS), showed improvements across a full range of subjective handicaps and psychological distress. Meanwhile, patients with physical neurotologic defects and minimal anxiety or depression did not benefit. The main causes of dizziness in patients without physical neurotologic findings were psychiatric disorders. |

| Another study by Horii et al. [21] compared Milnacipran (SNRI: serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor) and Fluvoxamine. The difference between these two medications was not significant. Moreover, they observed that patients with dizziness and psychiatric comorbidities have a significantly longer duration of symptoms and more handicaps than those without psychiatric disorders. |

| A study by Edelman et al. [22] focused on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). 41 patients with PPPD were divided in either treatment (n=20) or waiting–list group (n=21). Treatment was provided through 3 weekly sessions. They found that only 3 sessions of psychological intervention based on CBT offered a significant improvement in reducing the dizziness-related symptoms. Mahoney et al. [23] studied the long-term benefits of CBT and concluded that a brief CBT intervention produced sustained improvement. On the other hand, a previous study by Holmberg et al. [24] with a small group of 20 patients (one-year follow-up after CBT for phobic postural vertigo), did not show any significant treatment effects. |

| Thompson et al. [25] investigated habituation forms of vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy (VBRT) as a treatment for PPPD. This was a retrospective chart review and phone survey of 26 patients over an average timeframe of 27.5 months. Patients were assessed after receiving information about PPPD and instructions for homebased VBRT programs. Their results showed that the majority of PPPD patients found a vestibular habituation exercise program helpful. Greater improvements were made with sensitivity to head/ body motion than to visual stimuli. |

Discussion |

| There is evidence that the type of personality is related to PPPD symptoms. We found 3 publications on this topic [4,7,8]. Staab et al. [8] noticed that these patients are significantly more introvert, anxious with lower levels of trust. This is observed in patients with neurotic introverted personality traits. Furthermore, electrophysiological studies showed that highly neurotic introverts detected electro-cutaneous stimuli at lower thresholds than controls [26]. This shows that traits of personality may determine hyper-sensitivity to motion stimuli in PPPD patients. |

| As symptoms of VM, MD and PPPD are often overlapping, it is clear to us that there is a need for a precise diagnosis and re-evaluation of current diagnostic criteria for these disorders. Neff et al. [9] confirmed that PPPD patients were more often associated with VM and less commonly with MD. Furthermore, in a prospective study by Boleas-Aguirre et al. [27] where MD patients were treated with intratympanic gentamycin, 16% of the patients developed a PPPDlike picture despite excellent vertigo control. Neff et al hypothesized that PPPD may be mistaken in some cases for MD and may be leading to the vestibular ablative procedures which potentially aggravate the patients’ symptoms. |

| After reviewing the literature, it became obvious that PPPD presents a multisensory maladjustment. We found 4 studies that raised the hypothesis of altered sensory input in PPPD. Ödman et al. [12] observed that such patients process sensory inputs (somatosensory, vestibular or visual) insufficiently, even though their functions seem to be normal after neuro-vestibular examinations. Similar findings were done by Sohsten et al. [13]. Furthermore, Holle et al.[15] discovered that pain sensation threshold is decrease in PPPD. They suggested insufficient sensory information processing in PPPD patients that is not explained by vestibular system dysfunction. Finally, Indovina et al. [16] confirmed the reduction of activity in the key regions of the vestibular, visual and anxiety systems. |

| In our opinion, medication treatment of PPPD needs to be further investigated as the 3 relevant studies had small samples and lacked control groups. Staab and Ruckenstein [19] noticed that patients with clinically significant anxiety predating neurotologic illness might require more intensive interventions. Horii et al. [20] discovered that patients suffering from dizziness as well as anxiety and depression, responded better to SSRIs than those without. This trial however did not assess anxiety preceding neurotologic illness specifically. In cases of insufficient response to SSRIs in patients with psychiatric comorbidities, Milnacipran might be an alternative [21]. |

| Finally, we believe that CBT and VBRT are helpful as complementary treatments for PPPD. Among the 2 studies focussing on CBT interventions, Edelman et al. [22] concluded that CBT effects were sustainable, even after a therapeutic intervention set of only three sessions in a three weeks’ period. The patients on the waiting list served as control-group. Thompson et al. [25] conducted a phone survey, which confirmed the efficacy of VBRT in PPPD patients. |

Conclusion |

| PPPD is a frequent entity that has been only recently well described, with still limited literature support. Diagnostic criteria are based on anamnesis; posturography might help. High levels of neuroticism and introversion may be risk factors for developing PPPD, but not obsessive-compulsive personality type as previously stated. 25% of all cases may be triggered by neurotologic events. PPPD symptoms were more often associated with VM than with MD. Symptoms of VM, MD and PPPD are often overlapping, hence stressing the need for more precise diagnostic criteria. PPPD seems to stem from a multi-sensory maladjustment. There are alterations in activity and connectivity in the key central regions of the vestibular, visual and anxiety systems. Little progress has been made concerning pharmacological treatments: SSRI and SNRI seem to be helpful, but there is a need for larger controlled double-blinded trials to confirm their effectiveness. CBT as well as VBRT show a certain efficacy as complementary treatments for PPPD. |

References |

|