Clinical Image, J Trauma Stress Disor Treat Vol: 12 Issue: 3

Dynamic Spheres of Traumatic Dissociation Therapists Sketches

Lanza Juliana*

Licensed Psychologist, Traumatic Stress Unit, Emergency Psychiatric Hospital “Torcuato de Alvear”, Buenos Aires City, Argentina

*Corresponding Author: Lanza Juliana

Licensed Psychologist, Traumatic Stress Unit, Emergency Psychiatric Hospital “Torcuato de Alvear”, Buenos Aires City, Argentina

E-mail: julilanza@gmail.com

Received: 21-February-2023, Manuscript No. JTSDT-23-89313;

Editor assigned: 23-February-2023, PreQC No. JTSDT-23-89313(PQ);

Reviewed: 09-March-2023, QC No. JTSDT-23-89313;

Revised: 16-March-2023, Manuscript No. JTSDT-23-89313(R);

Published: 23-March-2023, DOI:10.4172/2324-8947.1000346

Citation: Juliana X (2023) Dynamic Spheres of Traumatic Dissociation Therapists Sketches. J Trauma Stress Disor Treat 12(3):346

Copyright: © 2023 Juliana X. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Keywords: Traumatic Dissociation, Traumatology

Introduction

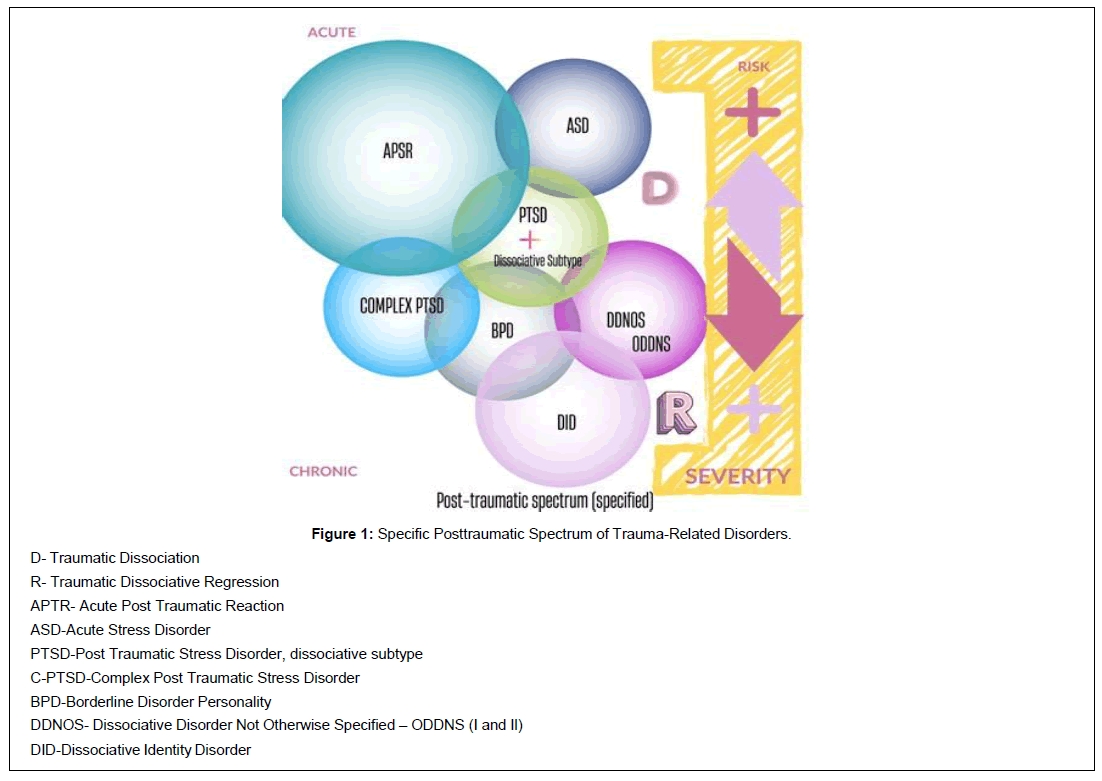

Considering integrative psychotraumatology training allows us to look through a transdiagnostic model lens [1]. Not just to looking for the pattern of trauma-related symptoms [2] and considering the primarily chosen psychotherapy model, but to look again across the clusters of all specific disorders. I call it a map of diagnostic spheres [3]. The tracking of diagnostic criteria through the broad and specific spectrum [4] of psychic trauma provides us with a radial look. This “trauma-transdiagnostic” viewer allows us to simultaneously record areas in which there would be various alterations of post-traumatic origin. This lense helps trauma therapists in considering what we are going to ask and what we could be omitting in our clinical consideration of the case. Case conceptualization is so dynamic that it demands an actively attentive therapeutic perspective. Gather the pertinent information to reach a more accurate presumptive diagnosis. And to choose, accordingly, what we are going to prioritize in flexible session planning. I think that the role of the therapist is very active [5] throughout the same session. And the attentive perspective on diagnostic variables is not quiet either. It also requires a global vision of certain observable variabilities at the beginning, but also throughout the treatment, because dissociation is not so mute or static. The patient’s dissociation is dynamic, it is felt, and it is essential to look at it in its relational aspect [6, 7]. Behind the evaluation of the “Acute Post-traumatic Reaction” a diagnosis could be masked previous and complex trauma-related disorders [8, 9]. The specific post-traumatic spectrum, integrated by disorders related to trauma, shows another side of the importance of immediate intervention as long as the acute post-traumatic reactions could occur due to a previous and/or latent traumatic process. This affects the exacerbation of the picture, the severity of its manifestations such as dissociation, regression, impulsivity and negative humor and cognitions, and different risk behaviours. The greater the severity, repetition and prolongued polyexposure to trauma (Julian Ford], the greater the fragmentation of the personality. The greater the fragmentation, the greater the breakdown for emotional tolerance. Simple PTSD: increased need for emotional activation (clue) (Figure 1).

Targeting the Targets

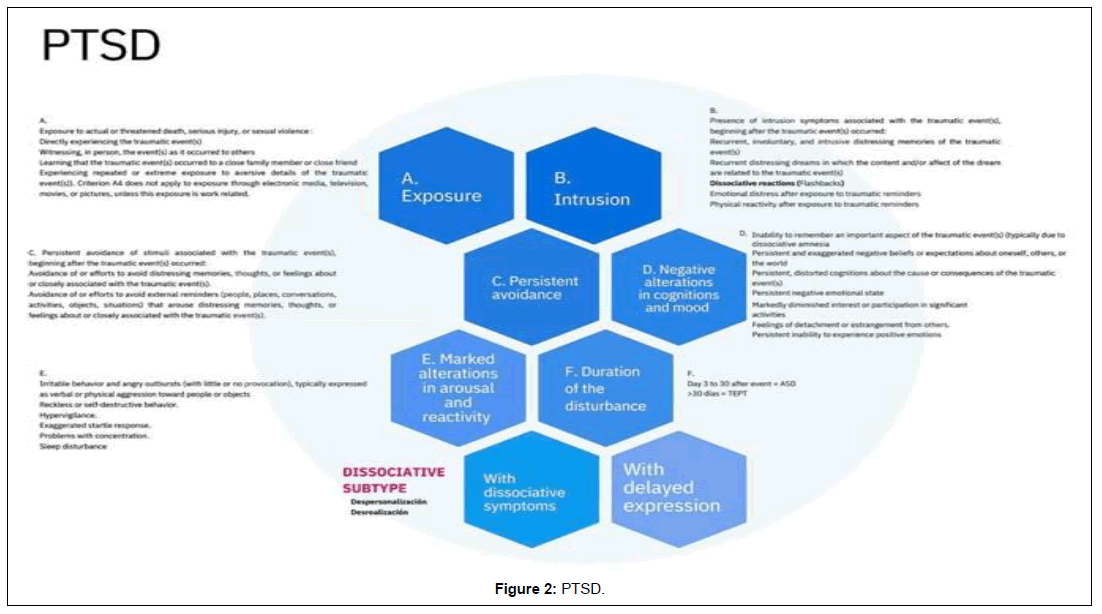

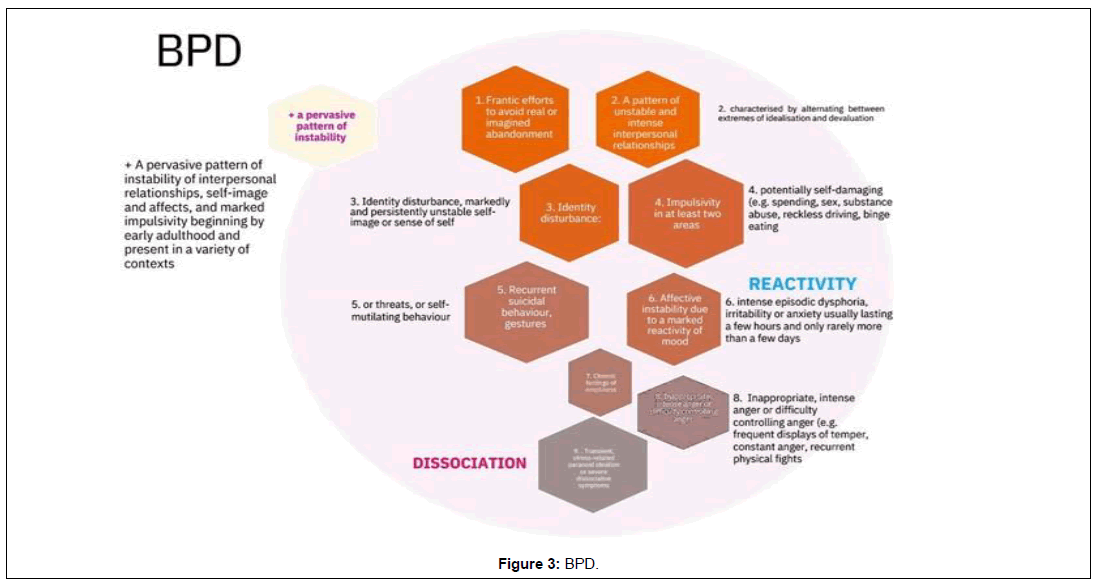

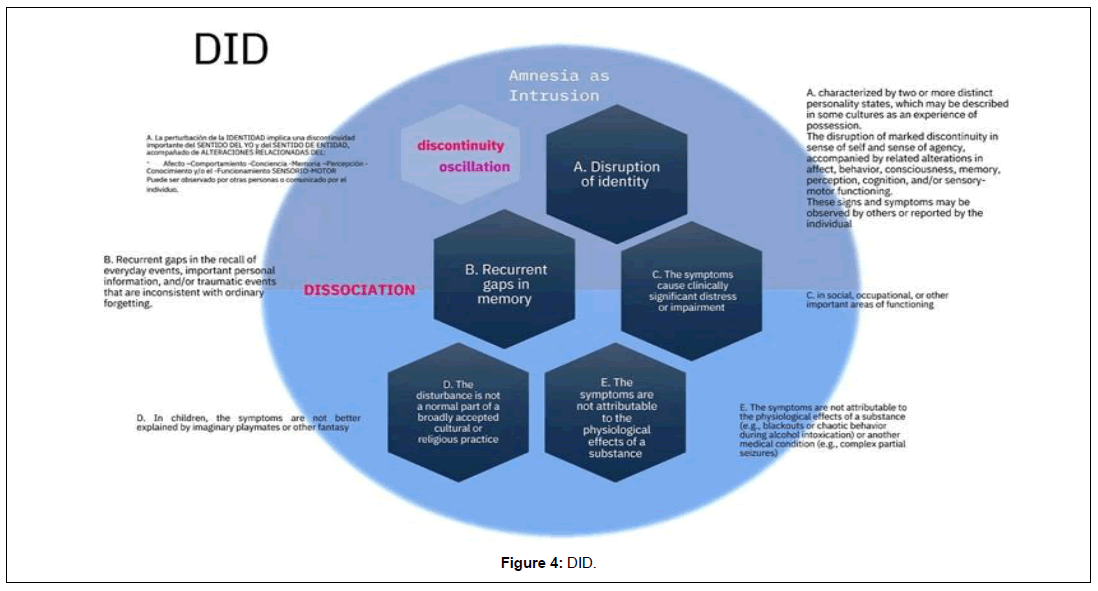

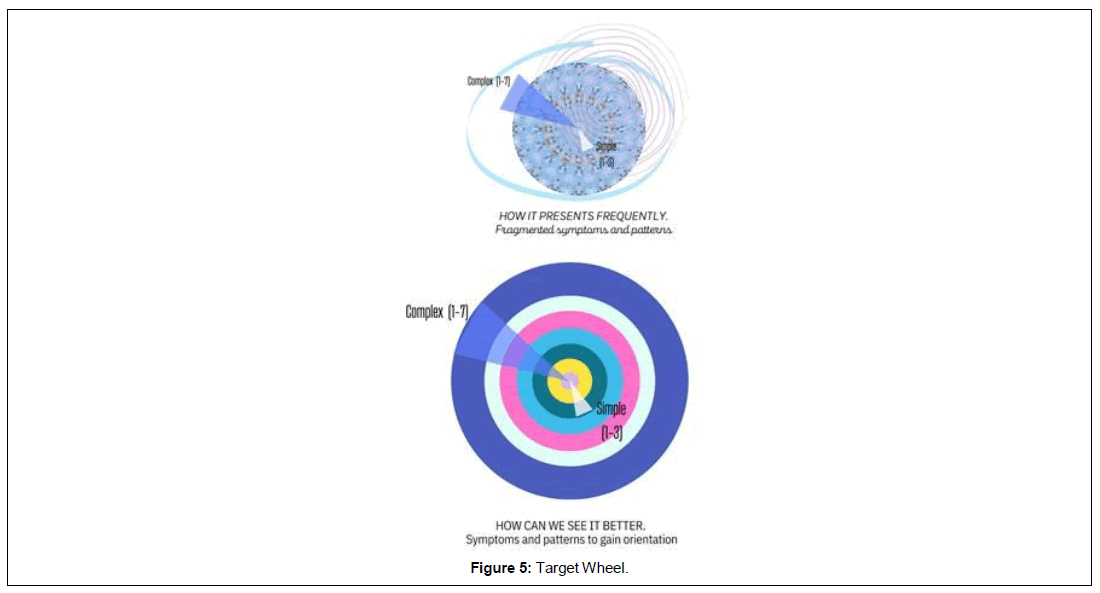

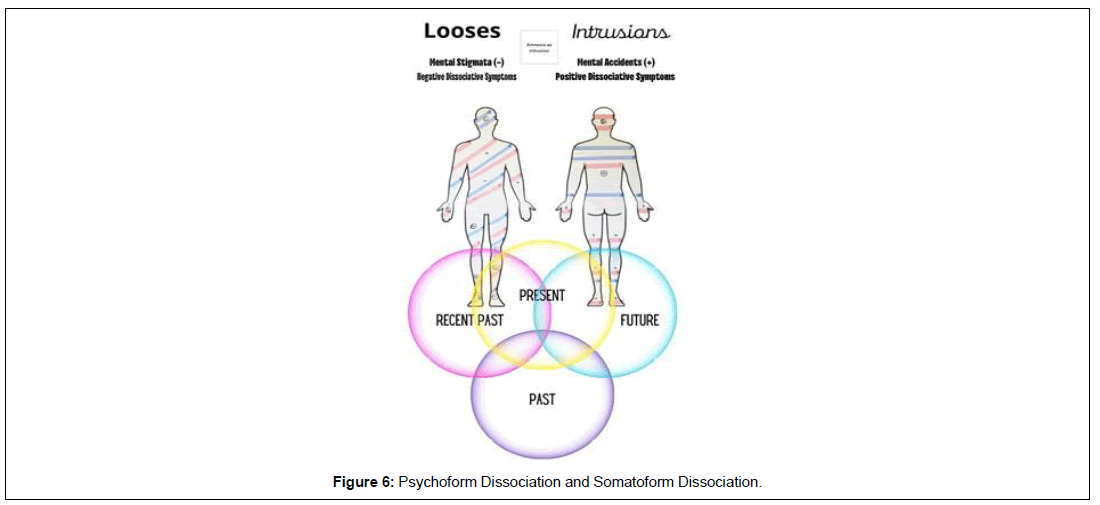

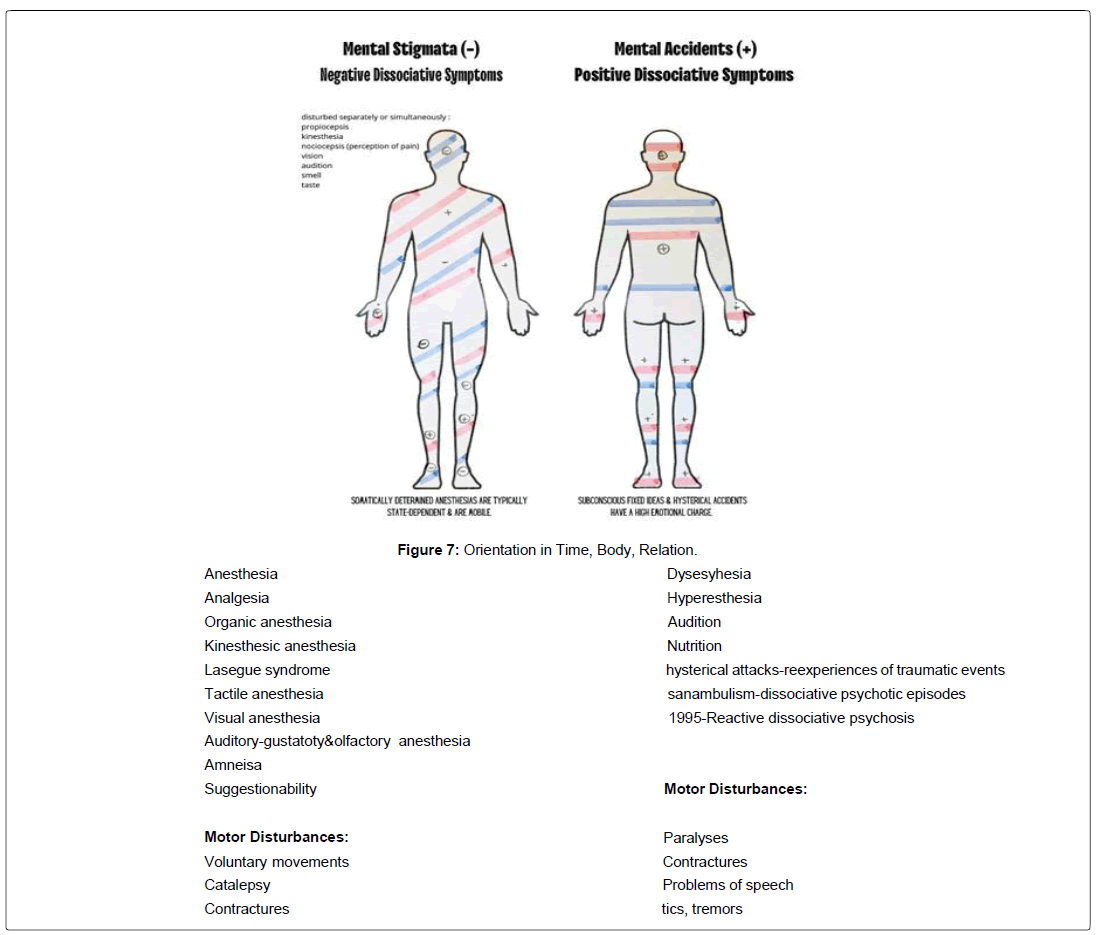

Safety Requires All Senses (Rothschild,2021), [10] Awareness and registration of the felt sensation or “felt sense” allows us to reflect maps of internal emotional states [11,12]. It facilitates an integrative look at various treatment models in the field of trauma therapies [13]. It is its clinical appreciation that can favor diagnostic evaluation and stabilization at the beginning, and in its continuation during the phases of treatment [14-17]. Clinical practice suggests that there is dissociation dynamic that manifests frankly in the somatic and relational areas, and that has a traumatic-dissociative origin. “Mapping” in this type of psychotherapy claims a sincere loan of value to the diversity of interventions that we carry out on a daily basis. Because one of the most common clinical difficulties are the modified approaches to the most severs disorders of complex trauma: any disorder that is not simple is not merely reduced to be “complex”, just as not every diagnosis related to trauma is “PTSD” [18] (Figure 2, 3). Starting by emphasizing the “felt sense” [11], the sensation felt in the body, as privileged sensory input [19, 20] allows us to use multiple register maps. It opens the door to the inclusion of a neurophysiological model of the dual activations of the autonomic nervous system [21, 22], and also to fragmented systems of dissociative parts. It is by tracing the psychoform dissociative symptomatology and simultaneously assessing the somatoform one, and together with the changing attachment patterns, that we access the diagnoses of trauma related disorders through a more direct route. The latter takes on greater importance as it allows us to classify the alteration or loss of certain previously acquired functions, especially manifest in Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) [23-26]. What are we going to look for? Areas. What kind of areas? Altered areas, viewed in an integrated way, through our trans diagnostic [27] spyglass. And to adjust our focus on the different overlapping layers in which the symptomatology is interrogated, and to achieve a case conceptualization that is more faithful to the gross clinical record [8, 28]. What are these simultaneously overlapping areas? We can give it a form of a target wheel that allows us to keep an eye on the diagnostic objectives on which we are going to work and re-evaluate in the planning and achievement of each treatment. Because patients do not come to the consultation molded to a type of conceptualization or a model of trauma psychotherapy already given (Figure 4).

And because patients sometimes arrive the opposite of what training they tell us is to be expected. To gain guidance on these difficulties, and to assess the symptoms and patterns that overlap in a fragmented way, as in a mosaic of tiles [8], we can force theory and practice to cross and define these discriminated areas as they appear on the wheel of 7 symptomatic areas. Both the sphere map and the diagnostic target wheel enable us to gain orientation, perspective and options as therapists, making use of tools that are provided by different trauma-based psychotherapeutic models. If we do it in an integrative way, the gain in resources is even greater. Usually, patients with more severity in the course of their disease have received several previous treatments, not only psychotherapeutic but also psychiatric and neurological ones, with a course of multiple medical-clinical consultations [26]. These are more frequently related to the presence of somatic symptoms that do not have a clear medical explanation. Sometimes, these treatments focus solely on the diagnosis of current symptoms without considering a dissociative and traumatic etiology. This not only makes psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment itself difficult, but also the prognosis and the choice of more effective and integrative interventions. The choice to include several fundamental theoretical models in the field of psychological trauma could entail the most direct path to diagnostic problems in complex trauma. With a dynamic perspective on dissociation, the application of the seven diagnostic spheres embedded in the wheel of diagnostic targets, favours the simultaneous vision of seven basic areas in the tracking of manifestations related to trauma. In the case of PTSD or Simple Trauma, the fragmentation of the traumatic experience would be assuming a dissociative process with a more or less mild to moderate gradient, and together with the other clusters. In dissociative disorders such as total or partial DID [24] (Figure 5), the form of re-experiencing is no longer simply pieces, but these tesserae are contained and made up of complex compartments (secondary and tertiary dissociation, structural theory of dissociation). These dissociated compartments of personality can easily be mistaken for loose and disordered fragments as they present in patients commonly diagnosed with ASD or PTSD [2]. Hence the importance of recording and evaluating dissociated emotional parts during the first interviews that could manifest through somatic and psychophysiological alterations, with observable changes in the patient’s body [24]. This fragmentation is characterize of lack of integration in the personality, and requires emphasizing the conflict between the different dissociative parts, which means not only recognizing dual autonomic activation in the patient, but also the utility and need of more active interventions by the therapist that will be resonating in a multiple counter-transferential way [29-37]. The dynamics of dissociation mobilizes us towards an integrated application of specific psychotherapeutic interventions and a particular consideration of the global perspective with which we begin the evaluation and treatment in psychotrauma (Figure 6,7).

References

- Frewen P, Lanius R (2015). Healing the traumatized Self. Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology.

- American Psychiatric Association (2014). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th Ed., Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, Pan American Medical Publishing House.

- Lanza J (2020). Diagnostic spheres and symptom registration form. Unpublished work: RE-2022-101291887-APN-DNDA#MJ.

- Lanza J (2019). Approach to Traumatic Stress, chapter. Unpublished non-musical work. Buenos Aires.

- Rosof Ann L (2019). How We Do What We Do: The Therapist, EMDR, and Treatment of Complex Trauma. J EMDR Pract Res 13(1):61-74.

- Marks-Tarlow T (2012). Clinical Intuition in Psychoterapy. The Neurobiology of Embodied Response. Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology.

- Fisher J (2017). Healing the fragmented selves of trauma survivors: Overcoming Internal self-alienation. Routledge.

- Lanza J (2017). Wooden Faces. Modeling Emotional Stabilization in Polyvictimized Adults. Digital File: download and online. Argentine Literature. 1st Edition, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Kindle Edition, Editorial Autores de Argentina.

- Herman J (1992). Desnos.

- Rothschild B (2021). Revolutionizing Trauma Treatment: Stabilization, Safety, & Nervous System Balance. ?W. W. Norton & Company.

- Mischke Reeds M (2018) Somagram, Somatic Pychoterapy Toolbox, Manuela, PESI Publishing Media.

- Ogden P (2010). Modulation, mindfulness, and movement in the treatment of trauma-related depression. Pat: (1-13).

- Van der Kolk B (2014). The body keeps the score. Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. Perm J 19(3):e118-e119.

- Shapiro F (2001,2004). Desensitization and reprocessing through eye movement, Editorial Pax México.

- Knipe J (2018). EMDR Toolbox. Theory and Treatment of Complex PTSD and Dissociation. Springer Publishing Company.

- Van Der Haart O, Nijenhuis ER, Steele K (2006). The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization. WW Norton.

- Nijenhuis E, Steele K, Van der Hart O (2005).Tratamiento Secuenciado En Fasesde La Disociación Estructural En La Traumatización Compleja:Superar Las Fobias Relacionadas Con El Trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 6(3):11-53.

- Van der Kolk B (2002). La naturaleza del trauma. Revista de Psicotrauma para Iberoamérica 1(1): 4-19.

- Schauer M (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress. Etiology and treatment. Maggie Schauer and Thomas Elbert. Journal of Psychology 218(2): 109-127.

- Schauer M, Thomas E (2010). Dissociation Following Traumatic Stress Etiology and Treatment. Journal of Psychology 218(2):109–12.

- Levine P, Poole Heller D (2018). Unrevealing the mystery of memory in the treatment of trauma.

- Levine PA (2015). Trauma and memory: Brain and body in a search for the living past: A practical guide for understanding and working with traumatic memory. North Atlantic Books.

- Nijenhuis E, Van der Hart O, Van der linden A (2007). Cuestionario De Disociacion Somatoforme, SDQ 20, -Amsterdam Leuven. Versión en Castellano por Olaf Holm.

- Dell P, O Neil J (2009). Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders DSM-V and Beyond. Psychology

- Nijenhuis E. (2004). Somatoform Dissociation: Phenomena, Measurement, and Theoretical lssues. WW Norton & Company.

- Frewen P, Kleindiens N, Lanius R, Schmahl C (2014). Trauma-related altered states of consciousness in women with BPD with our without co-occurring PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol.

- Lanza J (2019). DITRA. Microprocesamientos de la Disociación y el Trauma. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Austin M, Porges S, Riniolo T (2007). Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion regulation: insights from the polyvagal Theory. Brain Cogn 65(1):69-76.

- Bateman A, Fonagy P (2007). Mentalizing and borderline personality disorder. J Ment Health 16(1):83-101.

- Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Weiss B, Carlson EB, Bryant RA, et al (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Borderline Personality Disorder: A latent class analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol 15:5.

- Shepherd J (2015). Millie the cat has Borderline Personality Disorder. Blue Fox Press.

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5). Editorial Médica Panamericana.

- Paul F (Versión 6.0). MID. Dell, Ph.D.

- Van Derhart N, VanderlindenAssen AL (2007). Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire. Spanish version by Olaf Holm.

- Dell Paul F, John A. O'Neil, eds (2010). Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond. Routledge.

- Nijenhuis ER (2004). Somatoform Dissociation: Phenomena, Measurement, and Theoretical lssues. WW Norton & Company.

- Lanza J. Diagnostic spheres and symptom registration form. Unpublished work.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Therapist’s Sketches References

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi