Review Article, J Clin Exp Oncol Vol: 14 Issue: 4

Efficacy of interventions for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: An umbrella review

Yimeng Li1*, Mengmeng Ji2*, Mark A. Fiala3, Enkhjin Gansukh1, Natalia Neparidze4, 5, Martin W. Schoen6, 7, Xiaomei Ma1, 5, Graham A. Colditz2, Su-hsin Chang2 and Shi-Yi Wang1, 6

1Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology, Yale School of Public Health, USA

2Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, USA

3Division of Oncology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, USA

4Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hematology, Yale School of Medicine, USA

5Cancer Outcomes, Public Policy and Effectiveness Research (COPPER) Center, Yale University, USA

6Department of Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St Louis, USA

7Medical Service, St Louis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, St Louis, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Yimeng Li

Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology, Yale School of Public Health, USA

E-mail: yimeng.li@yale.edu

Received: 05-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. jceog-25-168171; Editor assigned: 06- Jun-2025, PreQC No. jceog-25-168171 (PQ); Reviewed: 20-Jun-2025, QC No. jceog-25-168171; Revised: 27-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. jceog-25-168171 (R); Published: 03-Jul-2025, DOI: 10.4172/2325-9620.1000345

Citation: Li Y, Ji M, Fiala MA, Gansukh E, Neparidze N, et al. (2025) Efficacy of Interventions for Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: An Umbrella Review. J Clin Exp Oncol 14: 345

Abstract

Purpose: Many systematic reviews have examined treatment efficacy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). We performed an umbrella review of these systematic reviews to provide a comprehensive examination of the current body of evidence, aiming to scope current review-level evidence and identify weaknesses in these reviews.

Methods: We identified systematic reviews examining efficacy of NDMM interventions in multiple databases published from January 1, 1990 through July 10, 2023. We explored potentially concerning issues which may compromise the validity of the conclusions in these reviews. We assessed the reviews’ quality, summarized the findings, and present potential evidence gaps.

Results: Eighty-seven reviews on NDMM treatment were included. Only seven assessed the strength of evidence. Treatments strategies like bortezomib-based induction for transplant-eligible patients, daratumumab for transplant-ineligible patients, and lenalidomide maintenance had moderate to high evidence. No reviews evaluated chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy or bispecific antibodies for NDMM. We identified five concerning issues: 1) inappropriate data abstraction (N=6), 2) inappropriate meta-analytic approaches (N=5), 3) not accounting for different induction strategies when evaluating the efficacy of consolidation/maintenance therapies (N=9), 4) implicit assumption that treatment efficacy is similar between transplant eligible and ineligible patients (N=13), and 5) inappropriate study selection (including observational studies or single-arm trials for treatment efficacy evaluation, which may lead to substantial biases; N=17).

Conclusion: This umbrella review provided a contemporary analysis of treatment efficacy for NDMM. We identified several weaknesses in existing reviews, indicating additional scrutiny of publishing systematic reviews in MM is warranted.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy of terminally differentiated plasma cells. Over the last three decades, the introduction of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and the availability of novel agents have changed the management of myeloma and extended median overall survival to 8-10 years.[1,2] However, MM is still considered incurable and virtually all patients will relapse, require multiple regimens for treatment, and die from MM or its sequalae. The proliferation of therapeutic targets for MM have stimulated a considerable surge in published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Likewise, the relative number of systematic reviews (SRs), to meticulously collate and analyze RCTs, has increased tremendously. The contributions of SRs in generating high-quality evidence that inform clinical practice and research directions are undeniable.[3] However, the influx of these resources can be overwhelming, potentially leading to a duplication of efforts, and may present contradictory findings. The ensuing complexity makes it challenging to navigate the landscape of MM research, emphasizing the critical need for an umbrella review to synthesize existing SRs and provide a comprehensive overview of the current evidence. An umbrella review, an essential tool in modern evidence-based medicine, is an SR of SRs. It can help in effectively navigating the research maze by serving as an overarching guide. To our knowledge, only two umbrella reviews for MM have been performed.[4,5] These umbrella reviews, however, are outdated. For example, newly FDA-approved agents for patients with MM, such as daratumumab which has become a backbone treatment in recent years, were not included. Furthermore, there has no comprehensive quality assessment of existing SRs. Therefore, we conducted an umbrella review to 1) summarize the findings from existing SRs of MM treatment efficacy, which can provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers; and 2) identify evidence gaps and weaknesses in the current SRs, thereby informing and guiding future SRs.

Methods

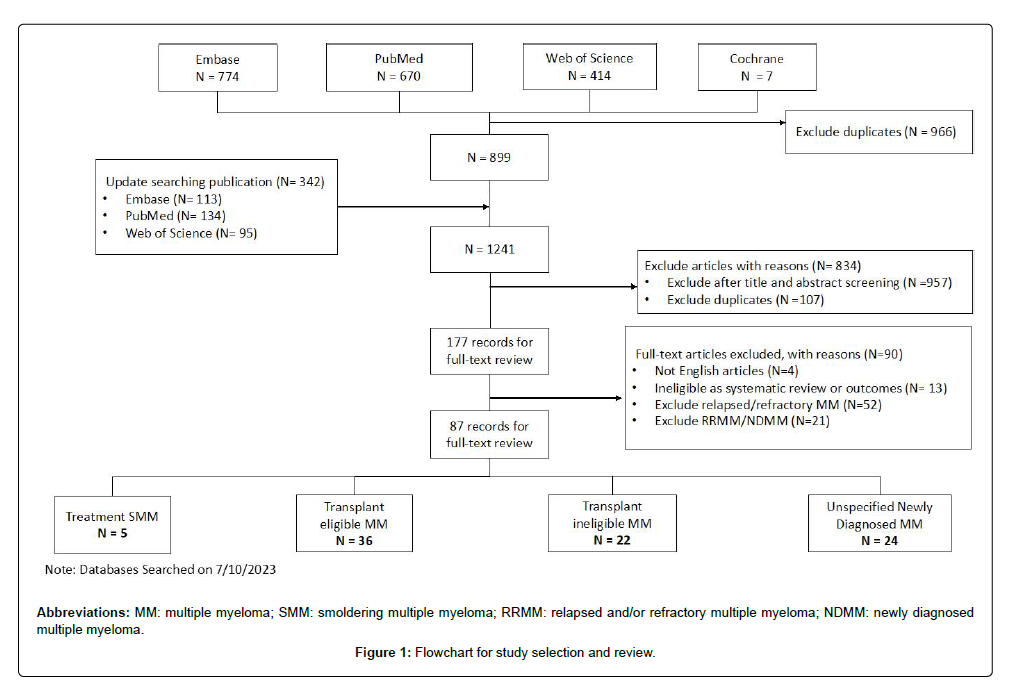

Literature search: We followed the PRISMA Statement for this umbrella review [6]. We conducted a comprehensive literature search for SRs and/or meta-analyses on MM in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane. The search was performed from January 1, 1990 to July 10, 2023. The search strategies for the four databases can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in our review, the articles had to 1) be SRs with or without meta-analyses; 2) be published in English; 3) assess systemic treatments for the newly diagnosed MM (including smoldering MM) population only; that is, articles involving relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) or other malignancies were excluded; and 4) report efficacy outcomes, including overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and response rates (overall response rate [ORR], complete response rate, or very good partial response rate). As we intended to assess the quality of existing SRs, articles were included even if they included non-RCT studies or did not report a clear search strategy. To exclude narrative reviews, articles which did not perform a meta-analysis had to contain the word “systematic” in the main text to be included. Reviews which only reported adverse events or outcomes not within our pre-specified outcome list or conference abstracts were excluded.

Data extraction

Two authors (Y.L and M.J) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify potential pertinent articles. Two authors (Y.L and S.W) reviewed the full-text articles, determined the eligibility, and assessed each study’s quality. Disagreement was resolved by consensus through discussion. For each SR, we abstracted information on the name of the first-author(s), year of publication, country, funding source, multiple myeloma type (e.g., transplant-eligible MM [TEMM], non-transplant-eligible MM [NTEMM], or unspecified), the intervention(s) of interest, the comparator(s), study type (whether a meta-analysis, network meta-analysis or individual participant data [IPD] meta-analysis was performed), inclusion of non-RCT data, the main findings, and their assessment of strength of evidence. For each SR, we not only abstracted the number of head-to-head RCTs included, but also reviewed these RCTs to identify any discrepancies between the SRs and the included RCTs.

Quality assessment

The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) evaluation tool was utilized to evaluate the methodological quality of SRs and meta-analyses that qualified for inclusion in this umbrella review. [7] We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) instrument to assess the strength of evidence [8].

Results

After removing duplicates, the literature search identified a total of 1241 potentially relevant records (Figure 1). Furthermore, 893 studies were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. Upon full-text reviews, 87 articles met the inclusion criteria. The population of interest was smoldering MM (SMM) in five reviews, TEMM in 36 reviews, NTEMM in 22 reviews, and unspecified NDMM (including reviews combining TEMM and NTEMM) in 24 reviews (Table 1). Nine reviews did not include meta-analyses, five performed IPD meta-analysis and 21 were network meta-analyses. Fifteen reviews addressed the question related to transplant, and 19 to consolidation/maintenance therapy. Twenty-six reviews were funded by industry. Detailed study characteristics can be found in Appendix 2.

| Number of reviews | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| Smoldering MM | 5 | 6% |

| TEMM | 36 | 41% |

| NTEMM | 22 | 25% |

| Unspecified NDMM | 24 | 28% |

| Including meta-analysis | ||

| Yes | 78 | 90% |

| Network meta-analysis | 21 | 24% |

| IPD meta-analysis | 5 | 6% |

| No | 9 | 10% |

| Funded by/Related to pharmaceutical companies | 26 | 30% |

| Country | ||

| USA | 20 | 23% |

| Canada | 4 | 5% |

| European countries | 24 | 28% |

| China | 33 | 38% |

| Others | 6 | 7% |

| Year of publications | ||

| older years (2013 and before) | 27 | 31% |

| 5 years before (2014 – 2018) | 26 | 30% |

| last 5 years (2019 - 2023) | 34 | 39% |

| Abbreviations: MM: multiple myeloma; TEMM: transplant-eligible multiple myeloma; NTEMM: transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma; NDMM: newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; IPD: individual participant data. | ||

Table 1: Review characteristics (N = 87)

Methodological quality of SRs

The methodological quality of reviews is displayed in Appendix 3. Forty-one reviews (47%) of the reviews provided an “a priori” design, indicating the existence of a protocol or ethics approval. Seventy-eight reviews (90%) executed a comprehensive literature search, and 39 studies (45%) described the included reviews in adequate detail. In terms of quality assessment [67] studies (72%) employed an existing checklist to evaluate the quality or risk of bias of included studies in their review. Only seven reviews assessed the strength of evidence [9–14] all except one using the GRADE instrument. These findings highlight the varying approaches and methodologies employed across the reviewed studies. Based on our assessment, strength of evidence was moderate or high in 53 SRs (60%; Appendix 4).

Evidence/Evidence gaps from SRs

Evidence addressed by the SRs and the potential evidence gaps are presented here according to the type of patient population (Table 2).

| Evidence | Future research |

|---|---|

| SMM | |

| Early treatment with lenalidomide (vs delayed treatment) improved PFS for SMM and high-risk SMM (Moderate) [15,17] | Will early treatment with lenalidomide improve OS in intermediate- and/or high-risk SMM? Will early treatment with daratumumab improve outcomes? |

| TEMM | |

| Induction: Bortezomib-based induction, compared to non-bortezomib-based induction, resulted in significant improvements in PFS and OS (High), Induction with combining immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors frontline regimens (in triplets) improved PFS and OS in TEMM (Moderate) [36] Daratumumab (Dara) induction improved ORR and MRD (Moderate) [37] | Will quadruplets (vs triplets) improve PFS and OS? |

| Transplant: HDC+HCT (vs chemo/delayed HCT) improved PFS but did not improve OS (High),, Tandem HCT (vs single HCT) did not improve PFS or OS (Moderate) [43] Auto-allo HCT (vs auto-auto HCT) did not improve PFS or OS (High) [40] Single HDT/HCT with VRD was superior to single HDT/HCT alone and standard-dose therapy for PFS (Moderate)[47] Upfront HDC+HCT improved OS in patients with MM harboring high-risk cytogenetics (High) [42] | Will CAR-T and bispecific T-cell engager therapy (vs transplant) improve outcomes? |

| Consolidation/Maintenance: IMiD maintenance therapy for patients with MM after HCT improved PFS and OS (High) [53,57,58,60] Lenalidomide maintenance (vs Thalidomide) improved PFS (Moderate) [68] | Will consolidation therapy improve outcomes? And if yes, which regimen? What is the best duration for maintenance therapy? |

| NTEMM | |

| Induction: Adding thalidomide or bortezomib improved OS and PFS (Moderate/High) [93,118–123] Dara-VMP, Dara-RD, VRD, VMPT-VT were the top regimens (Moderate) [11],69–74] Carfilzomib-based regimens did not improve OS and PFS, compared with the bortezomib-based regimens (Moderate) [75] | Will Dara-VRD (vs VRD) improve outcomes? |

| Maintenance: Maintenance therapy increased PFS in NTEMM patients (Moderate) [13] | What are the top maintenance regimens? |

| Unspecified NDMM | |

| Interferon improved PFS, and might have OS benefit (Moderate) [91,103] Old bisphosphonate drugs had no impact on mortality (Moderate) [76] Zoledronic acid improved OS for NDMM (Moderate) [77] Dara-based regimens improved PFS for TEMM and NTEMM patients (Moderate) [14] Lenalidomide-based maintenance improved PFS (Moderate) [78] Ixazomib maintenance improved PFS for TEMM and NTEMM patients (Moderate) [79] | Is INF still beneficial in current novel agent era? Will single-agent bortezomib or bortezomib-based maintenance regimens (vs. IMiDs) improve outcomes? Will ixazomib (vs lenalidomide) improve outcomes? |

| Abbreviations: MM: multiple myeloma; SMM: smoldering multiple myeloma; TEMM: transplant-eligible multiple myeloma; NTEMM: transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma; NDMM: newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; HDC: High-Dose Chemotherapy; CAR-T therapy: chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; HDT: high-dose therapy; VMP: bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone; RD: lenalidomide and dexamethasone; VRD: bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; VMPT-VT: VMP-thalidomide induction and bortezomib-thalidomide maintenance; IMiDs: Immunomodulatory imide drug. | |

Table 2: Evidence and evidence gaps

SMM

We identified five SRs, including 3 with meta-analyses [15–17] and 2 without [18,19] The number of RCTs included in each SR ranged from 2 to 8. Alkylators with MP can inhibit disease progression, but did not have impact on overall survival [20] Early treatment with immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) looks promising as two RCTs demonstrated early treatment with lenalidomide or zoledronic acid plus thalidomide improved PFS.[21,22] No evidence of benefits on OS of lenalidomide was found.22 We downgraded the level of evidence from moderate to low because patients on the control arm in QuiRedex trial were not provided lenalidomide on progression, nor was lenalidomide available outside of the trial, which does not reflect the standard of care during the study period nor current care; thus, the benefits of early treatment of lenalidomide would be overestimated. Additionally, this trial, beginning in 2007, did not routinely use free light chain assays to monitor early signals of progression, and the algorithm for identifying a patient as high risk was outdated.[23] As multiple risk stratification models have been developed to determine a patient’s risk of progression and the corresponding treatment,[24–27] future SRs examining the impact of IMiDs across different risk groups are needed. Also, daratumumab is very effective in MM treatment and has been evaluated in two trials; thus, comparisons between daratumumab and IMiDs would be of interest/importance.[28,29]

TEMM

We identified 37 SRs examining the treatment efficacy for TEMM, including 10 for induction therapy,[30–38,15] for transplant,[10,39–52] 10 for consolidation/maintenance therapy,9–61] and two for others. Because SRs may include observational studies only, the number of RCTs included in each SR ranged from 0 to 13. Regarding induction regimens, bortezomib-based regimens were included in seven reviews [31–36,38] and daratumumab was included in one review.[37] Evidence suggested that triplets (such as bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone [VTD] or bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone [VRD]) improves OS and PFS [32,33,36]. Dara-based regimens have demonstrated improved ORR and minimal residual disease (MRD) [37].While the CASSIOPEIA trial did use PFS as an endpoint, [62] the standard of care in the control maintenance arm of CASSIOPEIA was not adequate for US standards. Longer follow-up in the GRIFFIN trial is needed to confirm whether a PFS and OS benefit will be achieved. Additionally, more studies evaluating the high-risk subset of TEMM would benefit this population with an unmet need. Regarding transplant, nine SRs compared autologous HCT vs chemotherapy/deferred HCT, [10,41,42,44,45,47,49,52] 3 tandem vs single autologous HCT, [43,47,51] and 4 autologous-allogenous HCT [19,39,40,46]. While high dose chemotherapy (HDC) plus autologous HCT, compared to convention chemotherapy, improved PFS, it did not improve OS [41,44,49]. Additionally, patients with high-risk cytogenetics appear to benefit from early rather than delayed HCT.42 Tandem HCT (vs single HCT) and autologous-allogenous HCT (vs autologous- autologous HCT) did not improve PFS or OS. Evidence also suggested that HDC with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone plus HCT improved PFS but not OS [47]. Transplant is the standard of care for patients with TEMM, but comparisons between novel treatments, such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy [63–66] or bispecific T-cell engager therapy [67] vs transplant could help inform treatment recommendations. There were three SRs for consolidation therapy, [9,55,59] six for maintenance therapy, [53,56–58,60,61] and one for both consolidation and maintenance therapies.[54] While evidence regarding consolidation therapy was insufficient, evidence suggests that IMiD maintenance therapy for patients with MM after HCT improved PFS and OS [53,57,58,60]. Additionally, lenalidomide maintenance seemed to be better than thalidomide maintenance regarding PFS improvement [68]. Future research should examine whether consolidation therapy can improve outcomes; and if yes, identify the best consolidation regimens. From the value-based practice perspective, it would be important to determine if maintenance therapy could be stopped for patients who reach MRD-negativity, given the high cost of lenalidomide.

NTEMM

We identified 22 SRs examining the efficacy of induction therapy for NTEMM, including one IPD meta-analysis and 15 network meta-analyses. Evidence suggested that daratumumab plus vincristine, melphalan, and prednisone (Dara-VMP), daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Dara-RD), VRD, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide induction and bortezomib-thalidomide maintenance (VMPT-VT) were more effective and could improve PFS and OS, compared to other regimens [11–74]. Additionally, compared with the bortezomib-based regimens, carfilzomib-based regimens did not improve OS and PFS [75]. Regarding maintenance therapy for NTEMM, lenalidomide or ixazomib maintenance improved PFS but not OS [13]. Ongoing research will evaluate if Dara-RD or VRD-lite (i.e., revised VRD with lower intensity of therapy) is the preferred induction regimen and whether the addition of a fourth drug is beneficial among patients with NTEMM.

Unspecified NDMM

We identified 23 SRs examining the efficacy of different interventions for unspecified NDMM. Old bisphosphonate drugs, such as etidronate, clodronate, pamidronate, and ibandronate, had no impact on MM mortality,[76] whereas zoledronic acid improved OS [77]. Evidence suggested that daratumumab-based regimens improved PFS for patients with TEMM and NTEMM [14]. While one network meta-analysis concluded that lenalidomide maintenance appears to be the best treatment option, compared with thalidomide- or bortezomib-based regimens, the results in fact were not statistically significant [78]. Also, ixazomib maintenance therapy, compared to no maintenance therapy, improved PFS for patients with TEMM and NTEMM [79]. Future research comparing daratumumab or ixazomib with lenalidomide-based maintenance therapy is needed.

Concerning issues in SRs

We identified five concerning issues (Table 3). First, six reviews made some errors during the data abstraction stage [13,15–18,35]. Four reviews included duplicate studies, [15–18] even though the authors stated that two reviewers independently conducted data abstraction. Riccardi 1994 [80] is a subset study of Riccardi 2000 [20], and Musti 2003 [81] of D’Arena 2011 [82]; yet these were included as separate studies. One SR stated that it only included RCTs in their review, [35] yet an included study was in fact a retrospective matched case-control analysis [83]. One SR examined maintenance therapy for NTEMM, [13] but the population in one RCT was eligible to transplant [84].

| Inappropriate data abstraction (n=6) |

| Inappropriate meta-analytic approach (n=5) |

| Including different induction/consolidation strategies when evaluating efficacy of maintenance therapy (n=9) |

| Implicit assumption that treatment efficacy is similar between TEMM and NTEMM (n=13) |

| Including studies of inappropriate research design for treatment efficacy evaluation (n=17) |

| Abbreviations: MM: multiple myeloma; TEMM: transplant-eligible multiple myeloma; NTEMM: transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. |

Table 3: Concerning issues in existing systematic reviews

Second, five reviews applied an inappropriate meta-analytic approach [34,38,52,55,85]. Specifically, these authors calculated the outcomes of interest (complete response rate or PFS) for two groups in which patients were from different studies, and made conclusions based on the comparisons between the estimates. The conclusions are invalid as these reviews not only ignored the clustering within some head-to-head trials, but also did not account for the differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups.

Third, nine reviews [9,54,55,59,61,86–89] included RCTs in which patients who received two different consolidation/maintenance treatments but underwent different and non-comparable pre-maintenance therapies, and no stratification was performed. Given that the final outcomes could be related to the combined effect of both induction and maintenance in these trials, these RCTs are inappropriate for evaluation of consolidation/maintenance therapies.

Fourth, 24 reviews examined the efficacy of different interventions for unspecified NDMM [14,68,76–79,85,87–103]. The authors of these SRs did not separate TEMM and NTEMM, partially because the enrollment eligibility criteria of the original research included both TEMM and NTEMM. However, 13 SRs combined TEMM and NTEMM without conducting subgroup analyses by transplant status, which implicitly assumed that the treatment effect is similar for both groups [76,77,87,90–92,94,95,97,99–101,103]. Thus, the results of these SRs need to be interpreted with caution.

Fifth, 17 reviews included observational studies or single arm trials in their meta-analysis [9,10,34,35,38,39,46,50,52,55,56,85,99,100,104–106]. It is well known that for SRs of treatment efficacy, RCTs are more appropriate than observational studies, which are subject to selection bias.8 Thus, the conclusions based on these SRs may not be accurate. Furthermore, only two [9,10] of these 17 reviews assessed the strength of evidence (very low level of evidence in one [10] and unclear assessment in another [9]), making it difficult for appropriate interpretation of the reviews’ conclusion.

Discussion

This umbrella review systematically summarized and appraised the evidence for NDMM treatments. Eighty-seven reviews on NDMM treatments were included in the analyses, which showed that bortezomib-based induction regimens for transplant-eligible patients, daratumumab in the induction regimens for transplant-ineligible patients, and lenalidomide maintenance for NDMM were supported by a moderate or high level of evidence. Meanwhile, we identified five concerning issues which may compromise the validity of the review’s conclusion. Building upon two previous overviews4,5, this study provides updated evidence regarding treatment efficacy for NDMM, which can help physicians make treatment recommendations. The results of this umbrella review were largely consistent with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (category 1 or 2B) [107]. This includes VRD or Dara-VRD as the induction therapy for TEMM, autologous HCT for TEMM, VRD, Dara-RD, or Dara-VMP as the primary therapy for NTEMM, and lenalidomide or ixazomib for maintenance therapy. There are, however, some discrepancies between NCCN guidelines and our review. First, VMPT is not listed as one of the primary therapies for NTEMM in NCCN guidelines, even though there is moderate evidence to support its use. This is largely because the NCCN is a US-based guideline alliance, and US practices seldom, if ever, use melphalan or thalidomide in the era of novel agents due to toxicity profiles. Second, meta-analyses of two RCTs demonstrated the benefits of adding daratumumab for induction therapy in TEMM patients, [14,62,108] yet daratumumab-based regimens were not listed in category 1/2B regimens for TEMM. This is partly because GRIFFIN was a phase 2 trial and was not powered for PFS or OS. The PFS benefits were mainly driven by the CASSIOPEIA trial conducted in Europe, which utilized thalidomide [62]. It is worth examining the role of daratumumab induction for TEMM in the US, where lenalidomide is part of the standard care. Lastly, although carfilzomib is primarily seen as a replacement for bortezomib, evidence suggested that carfilzomib-based regimens do not improve OS and PFS compared to bortezomib-based regimens for NTEMM [75] or TEMM [109]. One caveat to note is that the ENDURANCE trial excluded patients with high-risk cytogenetics. Thus, the existing data does not completely inform us of the comparative efficacy of carfilzomib versus bortezomib-based triplet in this subset of patients. Our study indicated that most existing systematic reviews had some weaknesses that need attention. First, only 8% of the SRs identified assessed the strength of evidence. Even among the SRs published after 2014 (as the GRADE instrument was introduced in 2011), [8] 10% of them evaluated the strength of evidence. We identified five concerns compromising the review's validity. Although the SRs’ quality was fair based on the AMSTAR checklist, the issue of inappropriate data abstraction wasn't easily identified. Addressing this requires journal editors and reviewers to thoroughly review all eligible studies, highlighting the challenges in evaluating SR quality. We're not against SRs of observational studies. When data from RCTs are unavailable, well-conducted observational study SRs offer the best evidence. Yet, SRs of observational studies, without assessing evidence strength, can lead to inappropriate interpretation, especially concerning treatment efficacy.

Opportunities for future research

Our study identified important gaps in the literature which warrant further research (Table 3). As treatments for MM have evolved rapidly, effective treatments documented from early trials/SRs are likely to be outdated. Since novel agents are used as the standard of care, future research could examine new combinations that improve outcomes. Additionally, ongoing and future research should examine whether new regimens could be used earlier, such as daratumumab for SMM, and CAR-T or bispecific T-cell engager therapy for TEMM to replace transplant. Furthermore, the ongoing debate regarding the relative efficacy of quadruplet versus triplet regimens is a significant point of contention within the field. Unfortunately, a scarcity of systematic reviews exists on this topic, primarily due to the short-term follow-up for quadruplets and many trials still being in the early phase. Only a handful of SRs conducted meta-analyses or subgroup analyses by patients’ characteristics [10,15,39,42,110]. Future research should examine the treatment efficacy by an individual’s risk due to the current movement towards personalized medicine. Collaborative effort in conducting IPD meta-analyses is needed since they are more appropriate than traditional meta-analyses, with or without meta-regression for subgroup analyses. As MM diagnostic and classification criteria evolve [111–113] future studies must consider these changes to ensure consistent interpretation and application of research findings in a clinical setting. Diagnostic and risk-stratification criteria changes can influence the patient population included in trials and the generalizability of study outcomes. For example, recent inclusion of biomarkers like involved/uninvolved free light chain ratio and percentage of bone marrow plasma cells in MM diagnostic criteria has led to more SMM patients being diagnosed with clinical multiple myeloma [114]. These shifts must be accounted for in future studies to capture the disease’s full spectrum accurately, thereby better informing the development and implementation of treatment strategies and ultimately improving patient outcomes. The treatment landscape is evolving with innovative therapies, yet international disparities in drug approval and usage persist due to varying regulatory environments, drug availability, and differences in healthcare systems and funding mechanisms. For instance, lenalidomide plays a crucial role in the treatment protocols for newly diagnosed and relapsed MM patients in the United States, [115] serving both as an induction and maintenance therapy. Yet the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has limited the use of lenalidomide to specific scenarios due to cost-effectiveness concerns [116,117]. This discrepancy underscores the need for ongoing comparative research to understand how the same evidence base can lead to different treatment landscapes in different countries and their impact on patient outcomes worldwide. While the present umbrella review is the most comprehensive overview for treatment for NDMM, several potential limitations should be acknowledged. First, despite our search strategy encompassing multiple databases, we cannot eliminate the possibility of missing relevant systematic reviews. Second, evidence summarized in our overview was limited to results of published SRs. For example, results from well-conducted individual RCTs which have not been analyzed in SRs were not included, even though these RCTs could provide evidence with moderate strength. Nevertheless, this overview’s evidence base has a degree of overlap among the included SRs, which allowed us to compare and corroborate the results and conclusions from different studies. Third, our overview did not evaluate side effects from interventions for NDMM, nor efficacy of interventions for RRMM. Future umbrella reviews of these topics could help treatment decision-making.

Conclusion

Our overview reveals that treatment strategies for NDMM are evolving rapidly with significant advancements in therapeutics. We identified several methodological issues in existing SRs, indicating the need for further robust and systematic investigation. Because SRs play a pivotal role in clinical guideline development, future SRs should avoid the issues we have identified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U01 CA265735 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

Declaration of interest

Dr Schoen reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer and ConcertAI outside the submitted work. Dr Ma served as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr Colditz reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the conduct of the study. Dr Wang reported receiving grants from the American Cancer Society outside the submitted work. Dr Neparidze received research funding (institutional) from Janssen and GSK. None of these interests were related to the development of this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and PubMed database.

References

- Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA, Van Duin M, Sonneveld P, et al. (2017) Multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Dis Primer; 3:17046.

- Palumbo A, Anderson K. (2011) Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 364(11):1046-1060.

- Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne JA. (2011) Assessing risk of bias in included studies (Chapter 8). Cochrane Handb Syst Rev Interv Version; 5(0).

- Kumar A, Galeb S, Djulbegovic B. (2011) Treatment of patients with multiple myeloma: An overview of systematic reviews. Acta Haematol; 125(1-2):8-22.

- Aguiar PM, de Mendonça Lima T, Colleoni GWB, Storpirtis S. (2017) Efficacy and safety of bortezomib, thalidomide, and lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: An overview of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol; 113:195-212.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med; 3(3):e123-e130.

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, et al. (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol; 7:10.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence--imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol; 64(12):1283-1293.

- Gagelmann N, Kröger N. (2021) The role of novel agents for consolidation after autologous transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic review. Ann Hematol; 100(2):405-419.

- Mian H, Mian OS, Rochwerg B, Foley R, Wildes TM. (2020) Autologous stem cell transplant in older patients (age ≥ 65) with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Oncol; 11(1):93-99.

- Piechotta V, Jakob T, Langer P, Breuing J, Skoetz N, et al. (2020) Multiple drug combinations of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and thalidomide for first-line treatment in adults with transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2020(8).

- Kiss S, Gede N, Soós A, Hegyi P, Szabo I, et al. (2021) Efficacy of first-line treatment options in transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma: A network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol; 168:103504.

- Balitsky AK, Karkar A, McCurdy A, Rochwerg B, Mian HS. (2020) Maintenance therapy in transplant ineligible adults with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Haematol; 105(5):626-634.

- Chong LL, Soon YY, Soekojo CY, Ooi M, Chng WJ, et al. (2021) Daratumumab-based induction therapy for multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol; 159:103211.

- Zhao AL, Shen KN, Wang JN, Huo LQ, Li J, et al. (2019) Early or deferred treatment of smoldering multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis on randomized controlled studies. Cancer Manag Res; 11:5599-5611.

- He Y, Wheatley K, Clark O, Glasmacher A, Ross H, et al. (2003) Early versus deferred treatment for early stage multiple myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2003(1):CD004023.

- Gao M, Yang G, Tompkins VS, Li Y, Wang H, et al. (2014) Early versus deferred treatment for smoldering multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. PLoS One; 9(10):e109758.

- Ojo AS, Ojukwu SG, Asemota J, Akinrinlola O, Ojha H, et al. (2022) The effect of intervention versus watchful waiting on disease progression and overall survival in smoldering multiple myeloma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol; 148(4):897-911.

- Hernández JÁ, Martínez-López J, Lahuerta JJ. (2019) Timing treatment for smoldering myeloma: is earlier better? Expert Rev Hematol; 12(5):345-354.

- Riccardi A, Mora O, Tinelli C, Luoni R, Valentini D, et al. (2000) Long-term survival of stage I multiple myeloma given chemotherapy just after diagnosis or at progression of the disease: a multicentre randomized study. Br J Cancer; 82(7):1254-1260.

- Witzig TE, Laumann KM, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Hayman SR, et al. (2013) A phase III randomized trial of thalidomide plus zoledronic acid versus zoledronic acid alone in patients with asymptomatic multiple myeloma. Leukemia; 27(1):220-225.

- Mateos MV, Hernández MT, Giraldo P, de la Rubia J, de Arriba F, et al. (2016) Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus observation in patients with high-risk smouldering multiple myeloma (QuiRedex): long-term follow-up of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol; 17(8):1127-1136.

- Ludwig H. (2016) Early treatment for high-risk smouldering myeloma: has the time come? Lancet Oncol; 17(8):1030-1032.

- Lakshman A, Rajkumar SV, Buadi FK, Binder M, Gertz MA, et al. (2018) Risk stratification of smoldering multiple myeloma incorporating revised IMWG diagnostic criteria. Blood Cancer J; 8(6):59.

- Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, Therneau TM, Larson DR, et al. (2008) Immunoglobulin free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood; 111(2):785-789.

- Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, et al. (2007) Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 356(25):2582-2590.

- Pérez-Persona E, Vidriales MB, Mateo G, García-Sanz R, Mateos MV, et al. (2007) New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood; 110(7):2586-2592.

- Tan C, Usmani SZ. (2023) Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. The Hematologist; 20(2).

- Landgren CO, Chari A, Cohen YC, Jakubowiak AJ, Owen RG, et al. (2020) Daratumumab monotherapy for patients with intermediate-risk or high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma: a randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study (CENTAURUS). Leukemia; 34(7):1840-1852.

- Gao M, Chen G, Yang G, Tompkins VS, Li Y, Wang H, et al. Thalidomide-dexamethasone-based induction treatment before autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis.

- Wang L, Ran X, Wang B, Yan Y, Liu L, et al. (2012) Novel agents-based regimens as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Therapy for multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol; 30(2):57-61.

- Sonneveld P, Goldschmidt H, Rosiñol L, Bladé J, Lahuerta JJ, et al. (2013) Bortezomib-based versus nonbortezomib-based induction treatment before autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of phase III randomized, controlled trials. J Clin Oncol; 31(26):3279-3287.

- Nooka AK, Kaufman JL, Behera M, Ramakrishnan A, Muppidi S, et al. (2013) Bortezomib-containing induction regimens in transplant-eligible myeloma patients: a meta-analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Cancer; 119(23):4119-4128.

- Leiba M, Kedmi M, Duek A, Shvidel L, Berrebi A, et al. (2014) Bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (VCD) versus bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (VTD)-based regimens as induction therapies in newly diagnosed transplant eligible patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Br J Haematol; 166(5):702-710.

- Zeng ZH, Chen JF, Li YX, Qiu HX, Zhang Y, et al. (2017) Induction regimens for transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Manag Res; 9:287-298.

- Sekine L, Ziegelmann PK, Manica D, Viana M, Soares FM, et al. (2019) Frontline treatment for transplant-eligible multiple myeloma: A 6474 patients network meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol; 37(1):62-74.

- Menon T, Kataria S, Adhikari R, Menon V, Mahajan A, et al. (2021) Efficacy of daratumumab-based regimens compared to standard of care in transplant-eligible multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis. Cureus. Published online May 18, 2021.

- Yang G, Geng C, Jian Y, Wang M, Gao M, et al. (2022) Triplet RVd induction for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Ther; 39(8):3799-3834.

- Yin X, Tang L, Fan F, Zhang J, Li X, et al. (2018) Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2007 to 2017. Cancer Cell Int; 18(1):62.

- Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Hamadani M, Reljic T, Kumar A, Mohty M, et al. (2013) Comparative efficacy of tandem autologous versus autologous followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hematol Oncol; 6(1):2.

- Faussner F, Dempke WCM. (2012) Multiple myeloma: Myeloablative therapy with autologous stem cell support versus chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Anticancer Res.

- Chakraborty R, Siddiqi R, Willson G, Singavi A, Holstein S, et al. (2022) Impact of autologous transplantation on survival in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who have high-risk cytogenetics: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer; 128(12):2288-2297.

- Kumar A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Glasmacher A, Djulbegovic B. (2009) Tandem versus single autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for the treatment of multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst; 101(2):100-106.

- Koreth J, Cutler CS, Djulbegovic B, Behl R, Schlossman RL, et al. (2007) High-dose therapy with single autologous transplantation versus chemotherapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant; 13(2):183-196.

- Lévy V, Katsahian S, Fermand JP, Leblond V, Chevret S, et al. (2005) A meta-analysis on data from 575 patients with multiple myeloma randomly assigned to either high-dose therapy or conventional therapy. Medicine (Baltimore); 84(4):250-259.

- Armeson KE, Hill EG, Costa LJ. (2013) Tandem autologous vs autologous plus reduced intensity allogeneic transplantation in the upfront management of multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of trials with biological assignment. Bone Marrow Transplant; 48(4):562-567.

- Dhakal B, Szabo A, Chhabra S, Hamadani M, Hari P. (2018) Autologous transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in the era of novel agent induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol; 4(3):343.

- Hahn T, Wingard JR, Anderson KC, Bensinger W, Couriel D, et al. (2003) The role of cytotoxic therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the therapy of multiple myeloma: an evidence-based review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant; 9(1):4-37.

- Jain T, Sonbol MB, Firwana B, Khera N, Kumar A, et al. (2019) High-dose chemotherapy with early autologous stem cell transplantation compared to standard dose chemotherapy or delayed transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant; 25(2):239-247.

- Khorochkov A, Prieto J, Singh KB, Tam CS, Perales MA, et al. (2021) The role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: a systematic review of the literature. Cureus. Published online September 27, 2021.

- Naumann-Winter F, Greb A, Borchmann P, Engert A, Sieber M, et al. (2012) First-line tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation versus single high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma, a systematic review of controlled studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- Su B, Zhu X, Jiang Y, Zhang J, Wang L. (2019) A meta-analysis of autologous transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in the era of novel agents. Leuk Lymphoma; 60(6):1381-1388.

- Gao M, Gao L, Yang G, Jiang L, Wang L, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

- Liu X, He CK, Meng X, Zhang W, Zhai X, et al. (2015) Bortezomib-based vs non-bortezomib-based post-transplantation treatment in multiple myeloma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Phase III randomized controlled trials. OncoTargets Ther; 8:1459.

- Al-Ani F, Louzada M. (2017) Post-transplant consolidation plus lenalidomide maintenance vs lenalidomide maintenance alone in multiple myeloma: a systematic review. Eur J Haematol; 99(6):479-488.

- Zhong J, Zhang X, Liu M. (2021) The efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma patients after allo-hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med; 10(7):7736-7746.

- Kagoya Y, Nannya Y, Kurokawa M. (2012) Thalidomide maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma: meta-analysis. Leuk Res; 36(8):1016-1021.

- Ye X, Huang J, Pan Q, Liang J, Zhang W, et al. (2013) Maintenance therapy with immunomodulatory drugs after autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One; 8(8):e72635.

- Gao M, Yang G, Han Y, Jiang L, Kong Y, et al. Single-agent bortezomib or bortezomib-based regimens as consolidation therapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

- McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, Richardson PG, Hulin C, et al. (2017) Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol; 35(29):3279-3289.

- Parrondo RD, Reljic T, Iqbal M, Malhotra J, Hildebrandt GC, et al. (2021) Efficacy of proteasome inhibitor-based maintenance following autologous transplantation in multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Haematol; 106(1):40-48.

- Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, Arnulf B, Belhadj K, et al. (2019) Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet; 394(10192):29-38.

- Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, et al. (2021) Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet; 398(10297):314-324.

- Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, et al. (2021) Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 384(8):705-716.

- Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, Davies F, Moreau P, et al. (2023) Ide-cel or standard regimens in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 388(11):1002-1014.

- San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, Rodríguez-Otero P, O’Donnell E, et al. (2023) Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 389(4):335-347.

- Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, Nahi H, San-Miguel J, et al. (2022) Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 387(6):495-505.

- Zou Y, Sheng Z, Niu S, Li Q, Wen H. (2013) Lenalidomide versus thalidomide-based regimens as first-line therapy for patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma; 54(10):2219-2225.

- Ramasamy K, Dhanasiri S, Thom H, Balijepalli C, Nandakumar R, et al. (2020) Relative efficacy of treatment options in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results from a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma; 61(3):668-679.

- Blommestein HM, van Beurden-Tan CHY, Franken MG, Uyl-de Groot CA, Sonneveld P. (2019) Efficacy of first-line treatments for multiple myeloma patients not eligible for stem cell transplantation: a network meta-analysis. Haematologica; 104(5):1026-1035.

- Sekine L, Ziegelmann PK, Manica D, Viana M, Lima K, et al. (2019) Upfront treatment for newly diagnosed transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of 14,533 patients over 29 randomized clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol; 143:102-116.

- Giri S, Aryal MR, Yu H, Singal U, Khanal S, et al. (2020) Efficacy and safety of frontline regimens for older transplant-ineligible patients with multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Oncol; 11(8):1285-1292.

- Cao Y, Wan N, Liang Z, Jiang Y, Liu J, et al. (2019) Treatment outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for stem-cell transplantation: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk; 19(8):e478-e488.

- Facon T, San-Miguel J, Dimopoulos MA, Mateos MV, Orlowski RZ, et al. (2022) Treatment regimens for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Adv Ther; 39(5):1976-1992.

- Xie C, Wei M, Yang F, Fan L, Xiao Y, et al. (2022) Efficacy and toxicity of carfilzomib- or bortezomib-based regimens for treatment of transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore); 101(39):e30715.

- Djulbegovic B, Wheatley K, Ross H, Fairclough D, Bhandari S, et al. (2002) Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2002:CD003188.

- Wang X, Yan X, Li Y. A meta-analysis of the antitumor effect and safety of bisphosphonates in the treatment of multiple myeloma.

- Gay F, Jackson G, Rosiñol L, Holstein SA, Moreau P, et al. (2018) Maintenance treatment and survival in patients with myeloma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol; 4(10):1389.

- Chen H, Wang Y, Shao C, Liang H, Zhang Y, et al. (2021) Efficacy and safety of ixazomib maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Hematology; 26(1):1031-1039.

- Riccardi A, Ucci G, Luoni R, Mora O, De Paoli L, et al. (1994) Treatment of multiple myeloma according to the extension of the disease: a prospective, randomised study comparing a less with a more aggressive cystostatic policy. Br J Cancer; 70(6):1203-1210.

- Musto P, Falcone A, Sanpaolo G, et al. (2003) Pamidronate reduces skeletal events but does not improve progression-free survival in early-stage untreated myeloma: results of a randomized trial. Leuk Lymphoma; 44(9):1545-1548.

- D’Arena G, Gobbi PG, Broglia C, et al. (2011) Pamidronate versus observation in asymptomatic myeloma: final results with long-term follow-up of a randomized study. Leuk Lymphoma; 52(5):771-775.

- Cavo M, Zamagni E, Tosi P, et al. (2005) Superiority of thalidomide and dexamethasone over vincristine-doxorubicin-dexamethasone (VAD) as primary therapy in preparation for autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood; 106(1):35-39.

- Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. (2014) Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med; 371(10):895-905.

- Sheng Z, Li G, Li B, Liu Y, Wang L. (2017) Carfilzomib-containing combinations as frontline therapy for multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis of 13 trials. Eur J Haematol; 98(6):601-607.

- Wang X, Li Y, Yan X. (2016) Efficacy and Safety of Novel Agent-Based Therapies for Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res Int; 2016:1-17.

- Sun C yan, Li J ying, Chu Z bo, Zhang L, Chen L, Hu Y. (2017) Efficacy and safety of bortezomib maintenance in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Biosci Rep; 37(4):BSR20170304.

- Li JL, Fan GY, Liu YJ, et al. (2018) Long-Term Efficacy of Maintenance Therapy for Multiple Myeloma: A Quantitative Synthesis of 22 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Pharmacol; 9:430.

- Zhang S, Kulkarni AA, Xu B, et al. (2020) Bortezomib-based consolidation or maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J; 10(3):33.

- Chatziravdeli V, Katsaras GN, Katsaras D, et al. (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies of bisphosphonates and denosumab in multiple myeloma and future perspectives. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact; 22(4):596-621.

- Fritz E, Ludwig H. (2000) Interferon-alpha treatment in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 30 randomised trials among 3948 patients. Ann Oncol; 11(11):1427-1436.

- Huang H, Zhou L, Peng L, et al. (2014) Bortezomib–thalidomide-based regimens improved clinical outcomes without increasing toxicity as induction treatment for untreated multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis of phase III randomized controlled trials. Leuk Res; 38(9):1048-1054.

- Hicks LK, Haynes AE, Reece DE, et al. (2008) A meta-analysis and systematic review of thalidomide for patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma. Cancer Treat Rev; 34(5):442-452.

- Wang A, Duan Q, Liu X, et al. (2012) Bortezomib plus lenalidomide/thalidomide)- vs (bortezomib or lenalidomide/thalidomide)-containing regimens as induction therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Hematol; 91(11):1779-1784.

- Wang L, Cui J, Liu L, Sheng Z. (2012) Postrelapse survival rate correlates with first-line treatment strategy with thalidomide in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol; 30(4):163-169.

- Zeng Z, Lin J, Chen J. (2013) Bortezomib for patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Hematol; 92(7):935-943.

- Zou Y, Lin M, Sheng Z, Niu S. (2014) Bortezomib and lenalidomide as front-line therapy for multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma; 55(9):2024-2031.

- Gao M, Kong Y, Wang H, et al. (2016) Thalidomide treatment for patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Tumor Biol; 37(8):11081-11098.

- Vandross A. (2017) Proteasome inhibitor-based therapy for treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Semin Oncol; 44(6):381-384.

- Imtiaz H, Khan M, Ehsan H, et al. (2021) Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carfilzomib-Based Regimens for Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Review. OncoTargets Ther; 14:4941-4960.

- Gregory WM, Richards MA, Malpas JS. (1992) Combination chemotherapy versus melphalan and prednisolone in the treatment of multiple myeloma: an overview of published trials. J Clin Oncol; 10(2):334-342.

- Wang Y, Yang F, Shen Y, et al. (2016) Maintenance Therapy With Immunomodulatory Drugs in Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst; 108(3).

- The Myeloma Trialists’ Collaborative Group. (2001) Interferon as therapy for multiple myeloma: an individual patient data overview of 24 randomized trials and 4012 patients. Br J Haematol; 113(4):1020-1034.

- Gao F, Lin MS, You JS, et al. (2021) Long-term outcomes of busulfan plus melphalan-based versus melphalan 200 mg/m² conditioning regimens for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int; 21(1):601.

- Wang L, Xiang H, Yan Y, et al. (2021) Comparison of the efficiency, safety, and survival outcomes in two stem cell mobilization regimens with cyclophosphamide plus G-CSF or G-CSF alone in multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Ann Hematol; 100(2):563-573.

- Xu W, Li D, Sun Y, et al. (2019) Daratumumab added to standard of care in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A network meta‐analysis. Eur J Haematol; 103(6):542-551.

- Version 4.2023. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Multiple Myeloma. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1445 .

- Voorhees PM, Kaufman JL, Laubach J, et al. (2020) Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the GRIFFIN trial. Blood; 136(8):936-945.

- Kumar SK, Jacobus SJ, Cohen AD, et al. (2020) Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol; 21(10):1317-1330.

- Gil-Sierra MD, Briceño-Casado MDP, Fénix-Caballero S, et al. (2023) Daratumumab-based therapies in transplant-ineligible patients with untreated multiple myeloma and hepatic dysfunction: A systematic review of subgroup analyses. J Oncol Pharm Pract; 29(1):155-161.

- Rajkumar SV. (2016) Myeloma today: Disease definitions and treatment advances. Am J Hematol; 91(1):90-100.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. (2016) Multiple Myeloma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc; 91(1):101-119.

- Rajkumar SV. (2016) Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Staging System for Multiple Myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book; 35:e418-423.

- Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Mateos MV. (2015) Smoldering multiple myeloma. Blood; 125(20):3069-3075.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. (2020) Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J; 10(9):94.

- Overview | Lenalidomide for the treatment of multiple myeloma in people who have received at least 2 prior therapies | Guidance | NICE. (2009) June 18. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta171

- Overview | Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for multiple myeloma after 1 treatment with bortezomib | Guidance | NICE. (2019) June 26. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta586

- Kuhr K, Wirth D, Srivastava K, et al. (2016) First-line therapy for non-transplant eligible patients with multiple myeloma: direct and adjusted indirect comparison of treatment regimens on the existing market in Germany. Eur J Clin Pharmacol; 72(3):257-265.

- Picot J, Cooper K, Bryant J, et al. (2011) The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bortezomib and thalidomide in combination regimens with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid for the first-line treatment of multiple myeloma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess; 15(41):1-204.

- Kapoor P, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. (2011) Melphalan and prednisone versus melphalan, prednisone and thalidomide for elderly and/or transplant ineligible patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Leukemia; 25(4):689-696.

- Fayers PM, Palumbo A, Hulin C, et al. (2011) Thalidomide for previously untreated elderly patients with multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 1685 individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials. Blood; 118(5):1239-1247.

- Kumar A, Hozo I, Wheatley K, et al. (2011) Thalidomide versus bortezomib based regimens as first-line therapy for patients with multiple myeloma: A systematic review. Am J Hematol; 86(1):18-24.

- Lyu WW, Zhao QC, Song DH, et al. (2016) Thalidomide-based Regimens for Elderly and/or Transplant Ineligible Patients with Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl); 129(3):320-325.

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi