Research Article, J Regen Med Vol: 14 Issue: 1

Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Combination with Small Extracellular Vesicles Prevent the Development of Fibrosis and Cirrhosis and Improve Survival in Wistar Rats Receiving CCl₄

Sairam Atluri1*, Ajay Duseja2, Marwan Ghabril3, Ravi Bonthala1, Mounipriya Tamma1, Navneet Boddu4, Mohini Sridevi Kothapalli5, Sangaraju Rajendra5, Rohith Ganjam1, Anshuman Vangala1and Naga Chalasani3

1Tulsi Therapeutics Private Limited, ASPIRE BioNEST, School of Life Sciences, University of Hyderabad, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, India

2Department of Hepatology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

3Department of Gastroenterology, 550 University Blvd, Suite 1710, Indianapolis

4Advanced Pain and Regenerative Medicine, 3626 Ruffin Rd, San Diego. California, USA

5Cology Biosciences Private Limited, ASPIRE BioNEST, School of Life Sciences, University of Hyderabad, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, India

*Corresponding Author:Sairam Atluri

Tulsi Therapeutics Private Limited, ASPIRE BioNEST, School of Life Sciences, University of Hyderabad, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, India

E-mail: saiatluri@gmail.com

Received: 01-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. JRGM-25-166217; Editor assigned: 04- Jun-2025, PreQC No. JRGM-25-166217 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jun-2025, QC No. JRGM-25-166217; Revised: 01-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. JRGM-25-166217 (R); Published: 08-Aug-2025, DOI: 10.4172/2325-9620.1000347

Citation:Atluri S, Duseja A, Ghabril M, Bonthala R, Tamma M, et al. (2025) Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Combination with Small Extracellular Vesicles Prevent the Development of Fibrosis and Cirrhosis and Improve Survival in Wistar Rats Receiving CCl4. J Regen Med 14:1.

Abstract

Objective: Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UC-MSCs) and Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs) independently exert anti-inflammatory properties and have shown antifibrotic effects in animal models of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. In this proof-of-concept study, we examined the effects of human UC-MSCs combined with SEVs on liver fibrosis in a rat model of fibrosis and cirrhosis. Additionally, we studied the efficacy of UC-MSC and SEVs in improving survival.

Methods: Two groups of 14 male Wistar rats received six doses of oral CCl4. Starting at week 4, one group received three weekly IV doses of UC-MSC+SEV at a dose of 1 million MSCs and 5 billion SEV each. Fourteen animals who received CCl4 alone were used as control animals. All animals that survived until week seven were sacrificed.

Results: Liver fibrosis stage was significantly lower in the UCMSC+ SEV group (p<0.001). No animals in the UC-MSC+SEV group had cirrhosis, in contrast to the 12 animals in the control group with cirrhosis (p<0.001). Corresponding favorable changes in liver morphology, biochemistry, and immunohistochemistry were observed in the UC-MSC+SEV group. The difference in survival at 6 weeks was significant between the two groups (100% vs. 57%, p<0.01).

Conclusion: In this first animal trial, human UC-MSCs in combination with SEV prevented liver fibrosis and cirrhosis development in CCl4 induced liver disease and significantly improved animal survival. Further studies are needed to validate our observations and to test the combination of UCMSC+ SEV in other animal models and in humans with fibrotic liver diseases and liver failure.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Exosomes, Liver failure, Fibrosis reversal, Hepatic regeneration, Immunomodulation

Abbreviations

%: percentage; µg: microgram; α-SMA: Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin; A/G ratio: Albumin/Globulin ratio; ACTa2: Actin alpha 2 smooth muscle; ACTB: Actin Beta; AFP: Alpha Fetoprotein; ALB: Albumin; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BCA: Bicinchoninic Acid; BSA: Bovine Serum Albumin; BW: Body Weight; CCl4: Carbon Tetrachloride; CD63: Lysosomal membrane associated glycoprotein 3; CD81: Cluster of Differentiation 81; CD9: Cluster of Differentiation 9; CK18: Cytokeratin 18; CK19: Cytokeratin 19; COL1A1: Collagen type I Alpha1 chains; COL3a1: Collagen type III Alpha 1 chain; COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2; CCSEA: Committee for the Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals; CPCSEA: Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals; CTGF: Connective Tissue Growth Factor; DC: Disease Control; DCA: Drugs and Cosmetics Administration; DCGI: Drugs Controller General of India; E-Cad: E-Cadherin; EDTA: Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic Acid; ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay; FN: Fibronectin; g: grams; GSH: Reduced Glutathione; GPx: Glutathione peroxidase; H&E: Hematoxylin and Eosin staining; HO-1: Heme Oxygenase-1; HSP70: Heat Shock Protein 70; HUW-MSC+sEVs: Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells with small Extracellular Vesicles; i.v: intravenous; IAEC: Institutional Animal Ethics Committee; ICAM1, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; IL-1β: Interleukin-1beta; IL-6: Interleukin 6; iNOS: inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase; ISO: International Organization for Standardization; IκB: Inhibitor of kappa B; JNK1: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LD50: Lethal Dose 50; LPO: Lipid Peroxidase; M: male; mg: milligram; min: minutes; MMP-1: Matrix Metalloproteinase 1; MMP13: Matrix Metalloproteinase 13; MPO: Myeloperoxidase, MT staining: Masson's Trichrome staining; NABL: National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories; ng: nanogram; NO: Nitric Oxide; NOS2: Nitric Oxide Synthase-2; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor 2; PBS: Phosphate Buffered Saline; PC: Positive Control (CCl4 alone treated group); PDW: Platelet Distribution Width; pg: picogram; PKBa: Protein Kinase B alpha (PKB alpha/ Akt1); PSR: Picrosirius Red Staining; RIPA: Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay; RNS: Reactive Nitrogen Species; sEVs: small Extracellular Vesicles; SGOT: Serum Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase; SGPT: Serum Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminase; SMAD3: Mothers against Decapentaplegic Homolog 3; TC/TG: Test Control/Treatment Group; TD: Therapeutic dose; TGF-β1: Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1; TGF-β2: Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2; TIMP1: Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 1; TIMP3: Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3; TLR-4: Toll-Like Receptor 4; Tsg101: Tumor susceptibility gene 101; UC-MSCs: Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells; µL, microlitres; VCAM1: Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1

Introduction

The global burden of chronic liver disease is rising, currently afflicting approximately 1.5 billion individuals and resulting in 2 million deaths annually, constituting approximately 4% of all global mortalities [1-3]. Although hepatitis viruses remain the predominant etiological agents, there is rising concern regarding alcohol consumption and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) [3]. Although infrequently reported, it has a significant financial and psychological impact on patients and their families [1]. This underscores the urgent need for enhanced public health strategies to address the risk factors and mitigate the impact of chronic liver disease on global health outcomes.

Various therapeutic regimens, including dietary hygiene, alcohol abstinence, antiviral therapies, immunosuppressants (occasionally), and symptomatic treatments, are commonly used in the management of chronic liver failure of various etiologies, they have met with limited success. Regrettably, no medications are currently available to reverse fibrosis and cirrhosis, and liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment. However, challenges such as donor shortages, high costs, and requirement for long-term immunosuppression limit the scope of liver transplantation as a scalable solution. Recently, successful animal and clinical trials in the field of chronic liver disease have highlighted the potential of biological therapies, particularly Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and exosomes, to fill this therapeutic void.

MSCs possess anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, immunomodulatory, regenerative, anti-fibrotic, and angiogenic properties, which can be exploited to treat chronic liver diseases. Systemic delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) facilitates the conversion of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into antiinflammatory M2 macrophages via efferocytosis [4]. The injured liver releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and chemokines such as CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL10, which attract M2 macrophages [5]. Within the liver microenvironment, M2 macrophages facilitate an increase in regulatory T cells (Tregs) while simultaneously decreasing the populations of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells and enhancing the anti-inflammatory Th2 population. Furthermore, Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) play a role in increasing the population of Regulatory B cells (Tregs) and assisting the transformation of dendritic cells into cells that secrete Interleukin-10 (IL-10). They also contribute to a reduction in IL-17- secreting NKT17 cells and promote an increase in FoxP3+IL-10- secreting NKT regulatory cells (NKTregs) [6,7]. This immunomodulatory effect on various immune cells culminates in the increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IDO, IL-10, VEGF, HGF, IGF, TGF-β, NO, PGE, HO, EGF, FGF, and LIF, which suppress excessive inflammation and shift the local environment from a catabolic to an anabolic state, thereby stimulating dormant native hepatic stem cells and promoting liver regeneration. Transformed immune cells, along with activated native MSCs, secrete anti-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β (which can be pleiotropic), IL-10, and IL-1ra, modulate metalloproteinases, inhibit fibroblast activity, and reduce and potentially reverse fibrosis. In addition, the synthesis of proangiogenic proteins, including Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), activates endothelial cells, thereby facilitating neovascularization. A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of 11 randomized controlled clinical trials of MSCs in liver failure illustrated that MSCs improve liver function and exert protective effects against liver cirrhosis [8].

Another significant mechanism underlying the regenerative effects of MSCs is their paracrine activity, predominantly mediated through secreted Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs), specifically exosomes, which range in size from 30 nm to 150 nm [9]. Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs) originate from invagination of the plasma membrane, leading to the creation of Intraluminal Vesicles (ILVs). The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) pathway is essential to facilitate the integration of multiple ILVs into Multivesicular Bodies (MVBs). These MVBs encapsulate a variety of cytosolic components, including nucleic acids such as mRNA, miRNA, and lcRNA, as well as proteins and lipids [10]. In response to appropriate signals, Multivesicular Bodies (MVBs) merge with the plasma membrane, facilitating their release into the extracellular space as Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs) that are actively and purposefully taken up by other cells. Because SEVs contain cytosolic and genetic material derived from their parent cells, exosomes derived from MSCs modulate various immune cells by promoting their transformation into an anti-inflammatory regenerative phenotype, thereby contributing to the repair of injured tissues and organs, as described above. Exosomes can also transfer organelles, such as mitochondria, into injured cells and can be potentially anti-apoptotic. A pooled analysis of 38 animal trials revealed that exosomes improve liver function, promote the repair of injured liver tissue, and have therapeutic potential in the treatment of acute and chronic liver diseases [11].

The liver is an important immunological organ and a reservoir of multiple immune cells that delicately maintains homeostasis in the microenvironment, balancing inflammation and tolerance [6]. When hepatocytes sustain injury, they release Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) that activate inflammatory pathways and attract immune cells [12]. These recruited immune cells then produce proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-2a, IL-2b, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, culminating in excessive inflammation and consequent liver damage. MSCs and exosomes can modulate the hyperactive immune system as described above.

Animal studies have demonstrated that, while both Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and their derived exosomes independently reverse liver fibrosis with functional restoration, their mechanisms of action differ significantly and are mutually exclusive. To date, the synergistic potential of combining Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) with exosomes has not been investigated in animal or human clinical trials under various disease conditions. This proof-of-concept, first of its kind trial, was conducted to evaluate the potential enhancement of favorable outcomes by combining MSCs with exosomes.

Materials and Methods

Materials, reagents and kits

#Cat.No: 23227 Thermo Scientific Pierce BCA protein Assay kit, 0.2 micron filter; CD9, CD63, CD81, Calnexin, HSP-70 and TSG-101 (CNX) by using anti-CD9, anti-CD63, anti-CD81, anti-calnexin, anti- HSP-70 and anti-TSG101 (#Cat.No: ab275018, Abcam, US), respectively; anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (Cell Signaling Technologies #Cat.No: Anti-rabbit 7074); The bound specific antibody is illuminated using chemiluminescent reagents (Bio-Rad Clarity Max Western ECL substrate Bio-Rad; Cat. #1705062) in the ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc imaging system #Cat.No: 12003153). All ELISA kits for rat tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1; #Cat.No: SBEKR1023), rat matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13; #Cat.No: SBEKR2527), and rat matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-7; #Cat.No: SBEKR1179), Rat Albumin (ALB #Cat.No: SB-EKR1004), rat cytokeratin 19 (CK19; #Cat.No: SB-EKR2528), rat cytokeratin 18 (CK18; #Cat.No: SB-EKR1619), rat TGF-Beta-1, and rat IDO, and BCA Protein Assay kit (SARD Biosciences; Cat. #SB-AK1030), rat alpha fetoprotein (AFP #Cat. No. SB-EKR1094) was supplied by SARD Biosciences. The procurement of chemicals for the investigation involved acquiring water for injection from Aculife Company. DMSO, Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), trypsin, Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer, and other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100x) and phosphatase inhibitors were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. ProLiant New Zealand Ltd. provided Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Ketamine and xylazine were purchased from Troikaa Pharmaceuticals, Ltd. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and SARD Biosciences. COL1A1 (E8F4L) XP® Rabbit mAb #Cat.No: 7202–Cell signaling rabbit mAb recognizes endogenous levels of total COL1A1 protein; anti-alpha-smooth muscle actin (EPR5368)–ab124964 were procured from Allied Scientific Products, Kolkata; Cytokeratin 19 (A-3) is a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for epitope mapping between amino acids 7-29 at the N-terminus of Cytokeratin 19 of human origin #Cat.No: Sc376126 and Mouse monoclonal IgG3 κ from Santa Cruz and Cytokeratin 18 antibody (RGE53): sc-32329 and mouse monoclonal IgG1 κ from Santa Cruz. ALB/Albumin Antibody (F-10): sc-271605 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Alpha-fetoprotein (EP209)–Path in situ, AB Bioscience, and Rabbit Monoclonal (EP209) Clone EP 209.

hUC-MSC culture

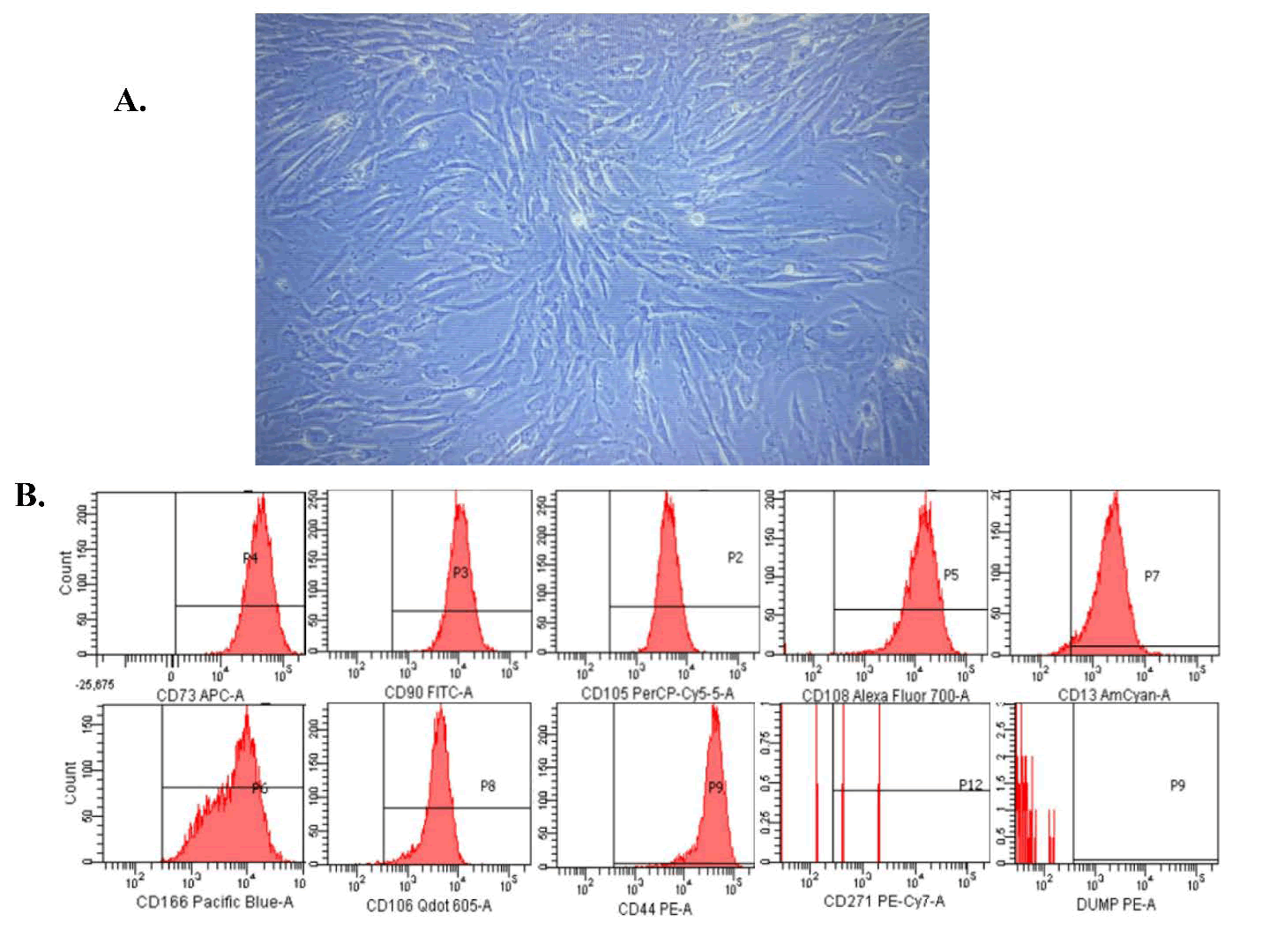

Umbilical cords were collected in a sterile manner from donors undergoing elective cesarean sections at term following proper donor screening and regulatory protocols. The cells were maintained in a standard stem cell culture medium enriched with serum. hUC-MSCs were harvested using enzymatic digestion and further cultured up to passage three to prepare them for therapeutic administration. At the time of infusion, the cell viability exceeded 98%, and the average cell diameter was less than 10 μm. Morphological assessment revealed cells with long, slender, and spindle-shaped characteristics (Figure 1A) typical of early passage Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). These cells satisfied the MSC criteria set forth by the International Society of Cell and Gene Therapy (ISCT) [13], demonstrating the presence of specific surface markers CD105, CD73, and CD90, while showing an absence of hematopoietic markers such as CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79α, CD19, and HLA-DR (Figure 1B). Additionally, plastic adherence and trilineage differentiation into adipose, cartilage, and bone tissues were noted, which is in agreement with the ISCT guidelines. MSC and exosome culture and isolation protocols have been optimized for large-scale manufacturing.

Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs) isolation

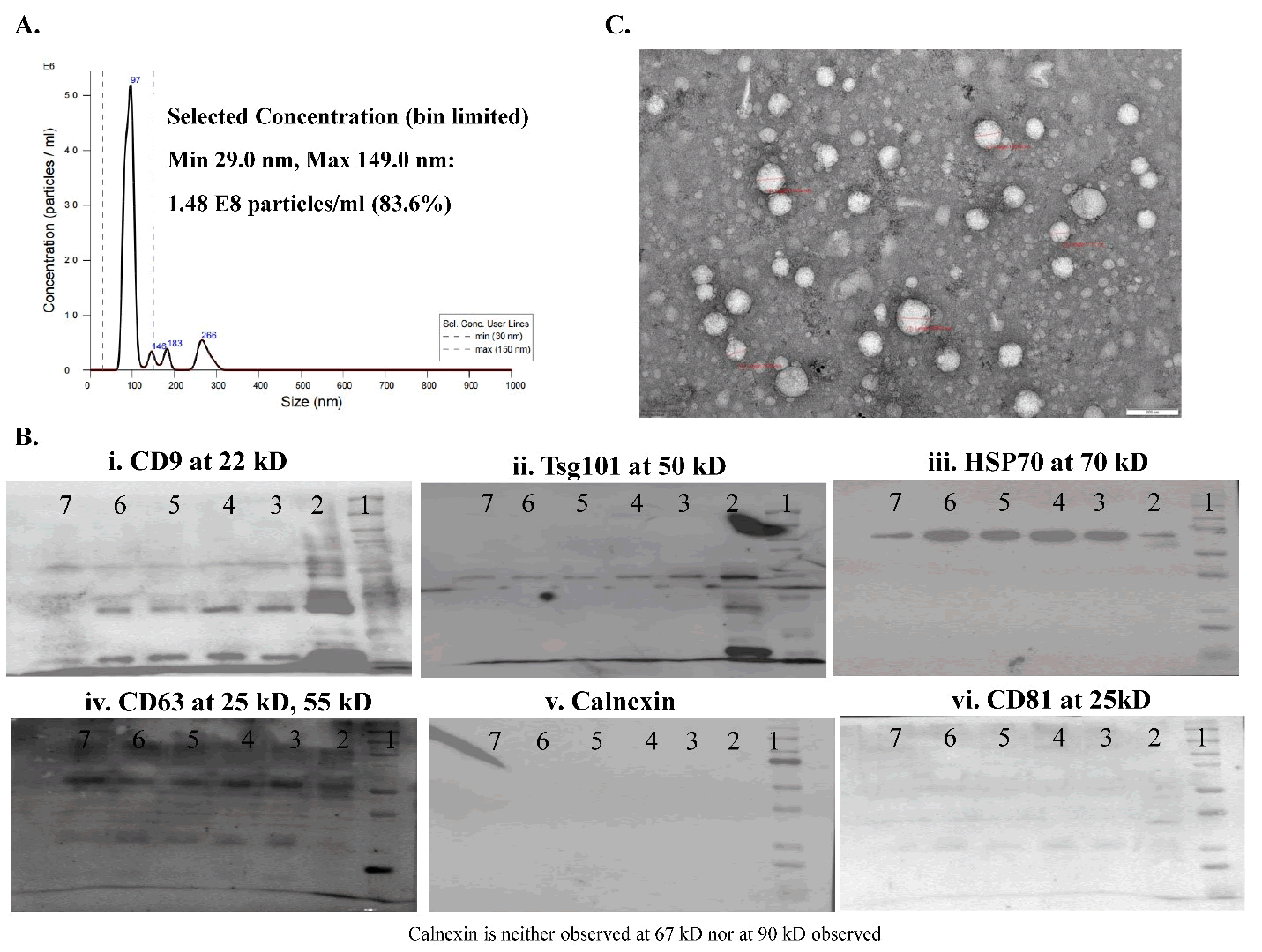

SEVs were isolated from the supernatants of the cultured UC-MSCs. The isolation process involved sequential microfiltration and ultrafiltration using filters of varying pore sizes to effectively separate and concentrate UC-MSC-derived SEVs. Following isolation, terminal sterilization was performed using a 0.2-micron filter. The purified SEVs were stored at -80°C until further use. SEVs met the MISEV criteria [9]. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) revealed that the SEVs had a mean diameter of 97 nm (Figure 2A) and a particle count of approximately 80 billion/mL. Western blot analysis revealed the presence of tetraspanins CD9 and CD63, the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) marker TSG 101, and exosomal immune modulator HSP70. The cellular contamination marker, calnexin, was negative (Figure 2B). The TEM images revealed the presence of rounded exosomes with intact lipid bilayers (Figure 2C).

Dose formulation preparation and storage

The test item was administered intravenously through the tail vein at a dose of one million hUC-MSCs immediately followed by 5 billion SEVs weekly, with a total of three doses administered, one each at weeks 4, 5, and 6 in the treatment groups (Table S3).

Experimental animals

This study was conducted using healthy male Wistar rats, weighing between 180 and 200 g and aged 7–8 weeks, at the University of Hyderabad Animal Facility, Hyderabad (CPCSEA Reg. No.151/1999/ CPCSEA/22.7.1999). Prior to the commencement of the experiments, the rats were acclimatized for seven days, during which they had unrestricted access to a standard pellet diet and water ad libitum. The animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions, which included a 12-hour light/dark cycle, a controlled temperature of 22 ± 2°C, and a relative humidity range of 40–70%. All experimental procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the CCSEA guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals, and the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of UoH/CB (approval no. UH/IAEC/MS/21/03/2024/08).

Experimental procedures

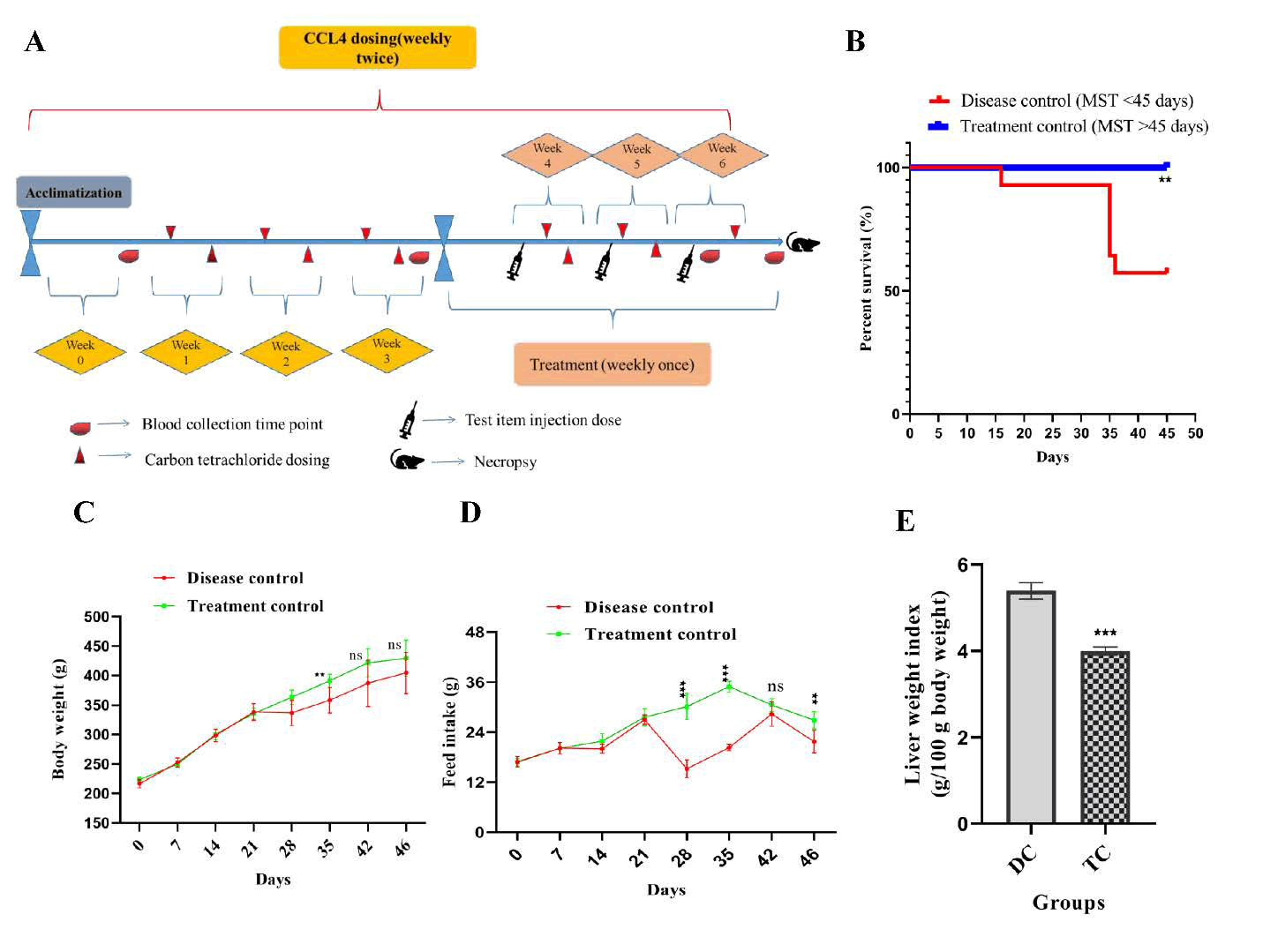

Following a 7-day acclimatization period, the body weights of the rats were recorded. Based on these measurements, the animals were randomized and divided into disease control and treatment groups. Starting from week 1 (with the acclimatization week designated as week 0), Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4) was administered orally to all animals at a dose of CCl4 1 mL/kg (diluted 1:1 in olive oil, v/v). The dosing was conducted twice weekly, with 2-3 days between consecutive administrations, continuing from weeks 1 to 6 (Table S3). Beginning at week 4, after three weeks of disease induction (six doses of CCl4 administered to all animals), the test item was introduced via intravenous injection into the tail vein of the treatment group. The test item was administered weekly with a total of three doses, one each at weeks 4, 5, and 6. Blood samples were collected at the following intervals: Week 0 (two days prior to the first CCl4 dose); week 3 (after the sixth CCl4 dose); week 6 (after the third treatment dose but before the final CCl4 injection); week 7 (on necropsy day, post-euthanasia) (Figure 3A). During necropsy, the liver and spleen were excised and cleaned with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) under aseptic conditions. The tissues were processed as follows. A portion of the liver tissue was stored at -80°C for subsequent cytokine analysis. The remaining liver tissue was preserved in 10% formalin for histological evaluation, which included Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, Masson's Trichrome staining, Sirius red staining, and immunohistochemistry for markers, such as ALB, AFP, CK18, CK19, MMP-13, TIMP-1, α-SMA, and collagen deposition. Biochemical markers were analyzed in the serum samples, including AST, ALT, ALB, globulin, A/G ratio, ALP, total protein, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, and total bilirubin. A portion of the liver tissue stored at -80°C was used for Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) to evaluate the expression of MMP-13, TIMP-1, TGF-β1, ALB, AFP, CK18, and CK19, and additional tissues were used for Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) to quantify markers, such as ALB, AFP, CK18, CK19, TIMP-1, MMP-13, TGF-β1, IDO, and IL-6. Blood was collected in EDTA tubes for hematological analysis, which included complete blood count, neutrophil count, mixed cell number, percentages of neutrophils, mixed cells, and lymphocytes, as well as hemoglobin, Mean Platelet Volume (MPV), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH), Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC), hematocrit, and platelet count. Blood collected in clot tubes, allowed to clot, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C to separate the serum, which was stored at -80°C until being dispatch to the designated test facility in accordance with sponsor recommendations.

Clinical observations

General clinical observations were performed daily throughout the study to monitor the animals’ health and behavior. Detailed clinical observations were performed during the study period. Behavioral and physiological changes in the animals were assessed using home cage observations, handheld evaluations, open-field activity assessments, and nervous and muscular measurements.

Body weights and organ index

Throughout the study, the body weight of the experimental animals was consistently tracked until the conclusion of the study. After euthanasia, the liver and spleen were carefully removed, rinsed with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and weighed immediately. The organ index, which is the ratio of wet organ weight to body weight, was determined by normalizing liver and spleen weights to the total body weight of the animals. The findings were reported in grams per 100 g of body weight (g/100 g BW). This analysis offers significant insights into the influence of the experimental conditions on organ size and overall systemic health.

For hematological analysis, assessment of biochemical parameters in serum and whole blood, RNA isolation and quality control, protein estimation, immunoblot analysis, histopathological analysis of liver tissues were performed.

Estimation of hematological parameters in blood

On the final day of the study, blood samples were collected from all experimental animals by using the retro-orbital plexus method. The samples were drawn into tubes containing the anticoagulant, dipotassium EDTA. Hematological parameters were assessed using a blood cell counter (Getein Animal Medical Automatic hhematology analyzer 3000Vet). The Parameters measured included total white blood cell counts, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, expressed as “× 103 cells/mm3” or as percentages. Differential cell counts, Platelet Distribution Width (PDW), and Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) were evaluated using a hematology analyzer. The results for PDW and MPV are presented in Femtoliters (fL), whereas other hematological data are expressed in standard units. This comprehensive analysis provided detailed insights into the hematological status of the experimental animals.

Assessment of biochemical parameters in serum

Blood samples were coagulated at room temperature for 2 h and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting serum was separated and stored at -80°C for subsequent analysis. Serum levels of Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) were quantified using commercial kits procured from Genuine Biosystems PVT Ltd. (India). These measurements were performed using Weldon biotech-WB-2416119. Biochemistry semi-autoanalyzer. All data are expressed in relevant units and biochemical parameters are presented in U/L. This protocol ensures precise and reliable serum evaluation.

Estimation of antioxidant activity in liver tissues

Liver tissue was homogenized (10% w/v in PBS) as described by Sangaraju et al. [14]. The supernatant was analyzed for Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) and reduced Glutathione (GSH), and the pellet was treated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged (1,800 × g, 10 min). The total protein content was determined via the BCA assay (BSA standard) using a microplate reader (Biotek Synergy H1). Reduced Glutathione (GSH) levels were measured using Ellman’s method (DTNB reaction), with concentrations derived from a standard curve (Sigma-Aldrich) and expressed as μg GSH/mg tissue. Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) activity was assessed at 420 nm (25°C), quantifying NADPH oxidation, and expressed as nmol NADPH/min/ mg tissue.

Assessment of gene expression analysis by using RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg of tissue using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, USA), eluted in 50 μL of nuclease-free water, and quantified using the Qubit® RNA BR Assay Kit (Life Technologies). RNA integrity was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (5 V/cm, 30 min in 0.5 × TBE buffer), followed by DNase treatment to eliminate DNA contamination. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using oligo(dT)18 primers and MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) in a 20 μL reaction (5 mM oligo(dT)18, 1 mM dNTPs, and 3 mM Mg2+). Duplicate reactions were pooled for each sample (40 μL). Primers were designed using Primer BLAST (NCBI) and validated in silico. The primers were synthesized by Macrogen Inc. (South Korea) and resuspended to 100 pmol/μL in nuclease-free water (primer sequences are listed in Table S2). qPCR was performed on a StepOnePlus system (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green (Takara Bio). The reactions (20 μL) contained 2 μL of diluted cDNA, 2X SYBR Green, 2.5 nM primers, and ROX dye. The cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C (30 s), 40 cycles of 94°C (5 s) and 60°C (30 s), followed by melt curve analysis. β-Actin served as the housekeeping gene, and the data were analyzed using Step One Plus and Data Assist software.

Estimation of cytokine levels in liver tissue via ELISA

Liver tissues from each animal were weighed, minced, and homogenized to a 10% concentration in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) containing a 1% Halt protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenates were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected for analysis. ELISA kits were used to quantify the levels of several proteins and cytokines in liver tissue supernatants. The assessed markers included albumin (ALB), measured in μg/mg of protein; pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, measured in ng/mg of protein; inflammatory mediator IDO, measured in ng/g of protein; Chemokines, such as AFP, measured in μg/mg of protein; fibrotic markers, including TGF-β1 (ng/g of protein), MMP-13, and TIMP1 (ng/mg of protein); and cytokeratin markers, such as CK18 and CK19, measured in ng/mg of protein. Protein concentrations in the liver samples were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) as the standard. The ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a BioTek Synergy H1 hybrid microplate reader. Cytokine concentrations in the liver tissues were reported as ng/ mg of protein, ng/g of protein, or μg/mg of protein, depending on the specific marker analyzed.

Histopathological analysis of liver tissues

On day 46, liver tissue samples from all experimental groups were collected, rinsed with cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The fixed tissues were processed using standard histological procedures, including dehydration through graded alcohols, clearing in xylene, and embedding in paraffin wax. Sections of 3–5 μm thickness were prepared using a Leica rotary microtome (Bensheim, Germany). For histopathological evaluation, the sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to assess general tissue architecture, Masson's Trichrome to visualize collagen deposition, and Picrosirius Red for detailed analysis of collagen fibers. Slides were examined in random order under a light microscope at magnifications of 40×, 100×, 200×, and 400×. Representative images were captured using a CILIKA BT-InviDigital semi-Apo-2021 microscope (MedPrime, India) for documentation and analysis.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Scoring

Tissue sections approximately 3-5μm thick were subjected to Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining for routine histological evaluation and Masson's Trichrome (MT) and PSR staining for collagen visualization. The severity of hepatic fibrosis was assessed using the NASH fibrosis score [15] (Table S3), which is a four-tier system derived from the METAVIR score [16]. The fibrotic area was quantified using image analysis. The histopathological grading of fibrosis was defined as follows (Tables S4 and S5): 0, no fibrosis; 1, periventricular and/or pericellular fibrosis; 2, septal fibrosis; 3, incomplete cirrhosis; 4, complete cirrhosis. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for cytoplasmic expression of AFP, ALB, α-SMA, Col1A1, CK-18, and CK19 in CCl4-Induced fibrotic liver disease. Tables S6 and S7 show the scoring system that enabled the semiquantitative assessment of AFP and albumin expression, providing insights into the extent of hepatocyte injury and progression of hepatic fibrosis in CCl4-induced fibrotic liver disease. Tables S8 and S9, the scoring system aids in the semi-quantitative assessment of Col1A1 and α-SMA expression, which correlates with the severity of fibrosis and HSC activation in liver disease models. Tables S10 and S11 provide a semi-quantitative assessment of CK18 and CK19 expression, correlating with the progression and severity of liver fibrosis. Semiquantitative analysis of fibrosis was based on the expression levels of IHC markers, such as AFP, ALB, α-SMA, Col1A1, CK-18, and CK19. The fibrosis score for each sample was calculated as the mean of the eight fields per slide. Consistency in fibrosis scoring was observed across pathologists, with minimal variation, and quantified using the Fiji (ImageJ) software.

Survival study

This study aimed to evaluate the mortality rate in rats subjected to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis induced by the administration of Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4). Mortality data were systematically recorded on a daily basis in the experimental animal facility from days 1 to 29, with observations continuing until the conclusion of the study on day 46. Survival rates across the experimental groups were analyzed using statistical methods and Kaplan-Meier survival curves, taking into account the observed mortality rates. The results were expressed as survival percentages over a 46-day period. These data provide insight into the survival dynamics of rats under CCl4-induced liver conditions.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (version 23.0) and GraphPad Prism software. The results from experimental investigations, including hematology, biochemistry, ELISA, body weight, feed intake, and liver index, were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. For comparisons between two groups, such as disease control versus treatment or test control groups, an independent sample t-test was employed to calculate p-values. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the data collected at different time points, including body weight and biochemical parameters. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed, and significance was determined using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical significance was denoted as follows: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001, while “ns” indicated nonsignificant results, all in comparison to the disease control group.

Results

Characterization of human UC-MSCs

Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UCMSCs) demonstrate a characteristic fibroblast-like spindle-shaped morphology when observed under phase-contrast microscopy during in vitro expansion (Figure 1A). Flow cytometric analysis verified the high expression of standard MSC surface markers CD73 (99.5%), CD90 (99.8%), and CD105 (98.3%). Conversely, there was minimal expression of the hematopoietic and immunogenic markers CD45, CD34, CD11b, CD19, and HLA-DR (<0.5%) (Figure 1B), thus fulfilling the minimal ISCT criteria for defining MSCs (Table S1).

Figure 1: Analysis of the morphology and surface markers of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) was conducted.

Note: (A) The illustration shows MSCs with a slender, spindle-shaped morphology during attachment culture at 90% confluency. (B) Flow cytometric analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) CD markers on MSCs. The analysis included positive surface markers CD73, CD90, and CD105, as well as negative markers CD34, CD11b, CD19, CD45, and HLA-DR, utilizing the Human MSC Analysis Kit. The data are presented as the mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) from three independent experiments (n=3).

Characterization of Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs)

Small Extracellular Vesicles (SEVs) isolated from culture supernatants of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UC-MSCs) were characterized by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Western blotting, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). NTA results indicated that the SEVs had a mean diameter of 97 nm, with a size distribution within the typical exosomal range of 30–150 nm (Figure 2A). Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of the exosomal markers CD9, CD63, and TSG101 (Figure 2B). TEM images revealed intact spherical vesicles with a cup-shaped morphology and a lipid bilayer membrane, consistent with the ultrastructural characteristics of SEVs (Figure 2C).

Figure 2: Characterization and Identification of exosomes and Western blot analysis.

Note: (A) The NTA spectrophotometric graph illustrates the diameter and particle number of exosomes using the nanoparticle tracking analyzer. (B) The expression of various markers in the exosomes is analyzed by Western blot. (C) Exosomes are examined under a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM). Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n=3).

Physiological and macroscopic effects

Rats exposed to CCl4 exhibited progressive weight loss and reduced feed intake, both of which were significantly ameliorated by UC-MSC +SEV treatment on day 35 (p<0.001; Figures 3C–D). The treated group regained body weight (P<0.001) by day 35, whereas the disease group continued to decline. However, no intergroup differences were observed at 42 or 46 days. Notably, the disease group showed pronounced weight loss after the third week, which was reversed in the treated animals, along with improvements in liver weight (Figures 3C and 3E). Behavioral observations indicated reduced lethargy in treated rats from day 28 to 35 and at day 45, although no differences were noted at day 42–46. The liver index (liver-to-body weight ratio) was significantly higher in the disease group, but stabilized in the treated animals (Figure 3E).

Figure 3: (A) The experimental design encompassed the timing and frequency of blood collection, necropsy, and the administration of CCl4, MSC, and exosome doses. (B) A Kaplan-Meier survival plot was utilized. (C) Alterations in body weight and (D) changes in feed intake were observed in both the disease control and treated animal groups. (E) Variations in the liver weight index between the two groups were assessed. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=14). Kaplan- Meier survival analysis was employed, and statistical significance was evaluated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance in the treatment group is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 when compared to the disease control group; ns denotes non-significance.

Immunomodulatory impact of UC-MSC+SEV treatment restores hematological, biochemical, and antioxidant parameters in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

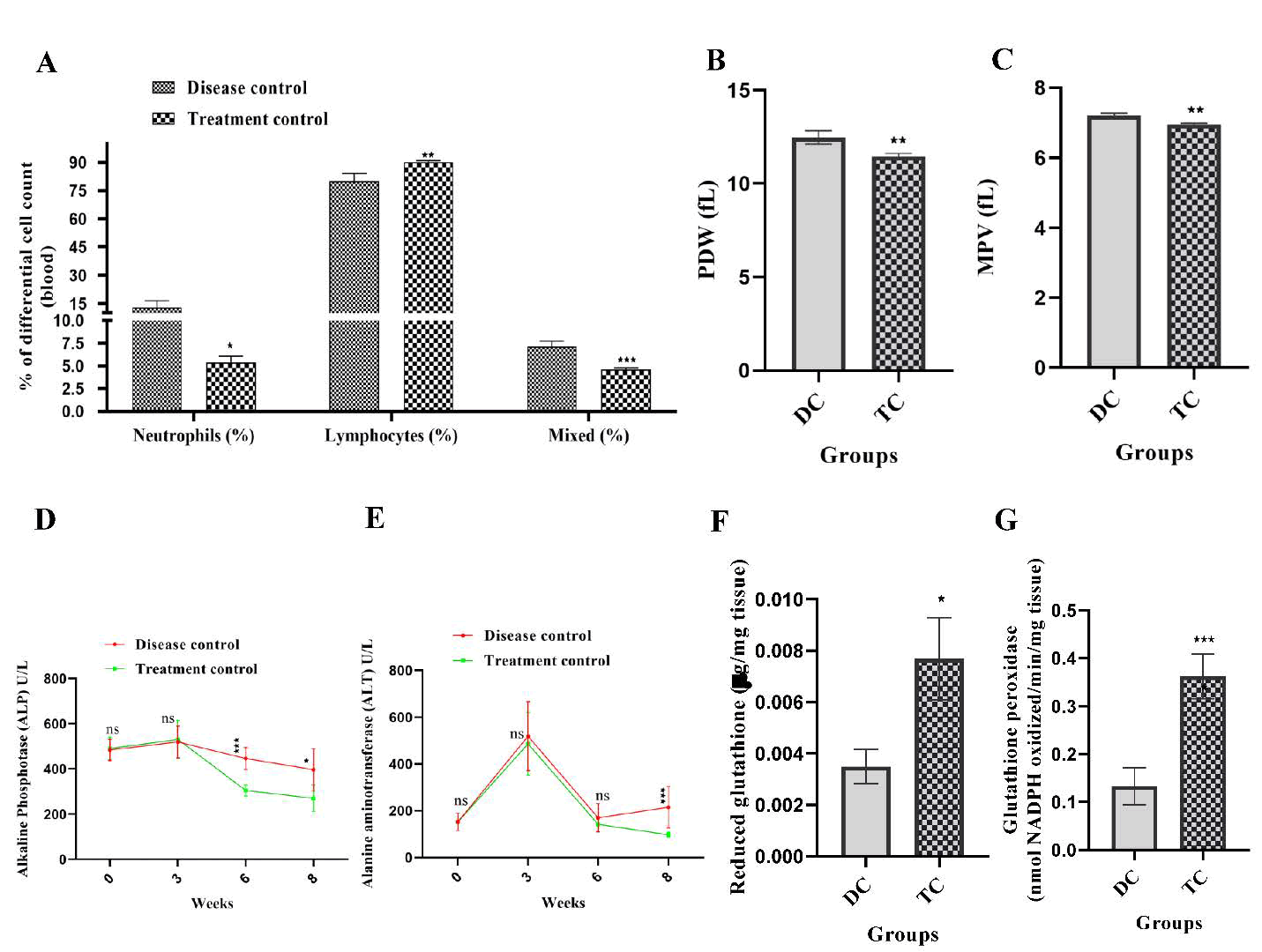

Hematological parameters: The therapeutic efficacy of UC-MSCs combined with SEVs in mitigating CCl4-induced liver fibrosis was further corroborated by hematological evaluation, specifically focusing on differential blood cell counts and platelet parameters. Administration of CCl4 led to significant alterations in the hematological profile, indicative of systemic inflammation and liver dysfunction. CCl4-induced liver injury results in notable hematological abnormalities, including reduced Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) and elevated Mean Platelet Volume (MPV), which is indicative of thrombopoietic stress. These parameters were significantly restored following therapy (PDW, p<0.01; MPV, p<0.01; Figures 4A–B). The disease group also exhibited neutrophilia and lymphopenia, both of which normalized in the treated rats (Figure 4C). In the disease cohort, there was a notable increase in neutrophil percentage (p<0.05), a decrease in lymphocyte percentage (p<0.01), and a significant increase in the mixed-cell population (eosinophils, basophils, and monocytes) (p<0.001) compared to the treated group. These changes reflect heightened immune and inflammatory responses associated with progressive liver fibrosis. Moreover, Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) and Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) were significantly elevated (p<0.01) in the disease group, suggesting increased platelet activation and potential hepatocellular damage. Treatment with UC-MSCs+SEVs effectively reversed these abnormalities and restored the hematological parameters to normal levels. Compared with the disease group, the treated group exhibited a significant reduction in neutrophil percentage (p<0.05), an increase in lymphocyte percentage (p<0.01), and a decrease in the mixed-cell population (p<0.001) (Figure 4A). Additionally, PDW (Figure 4B) and MPV (Figure 4C) were significantly reduced (p<0.01) in the treated group, indicating reduced platelet activation and inflammation, which aligns with the diminished fibrogenesis and hepatocellular stress. These findings underscore the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of UC-MSCs +SEVs on hematological profiles in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. By normalizing the immune cell dynamics and platelet function, UCMSCs+ SEVs demonstrated their potential to mitigate systemic inflammation and promote hepatic recovery under fibrotic conditions.

Biochemical parameters: The therapeutic efficacy of UC-MSCs combined with SEVs in ameliorating liver fibrosis was further elucidated through a comprehensive analysis of key biochemical markers in the liver tissues of CCl4-treated rats. As illustrated in Figures 4D and E, the disease group exhibited significant dysregulation in serum biochemical parameters, indicative of hepatic injury and fibrosis progression. Serum levels of Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), markers of hepatocellular and biliary damage, were markedly elevated in the CCl4 group (p<0.001) and significantly reduced following UC-MSC+SEV administration (p<0.001, Figures 4D and E). In the CCl4-treated disease group, a notable increase in ALP activity was observed at weeks 6 and 8, accompanied by a marked elevation in ALT levels at week 8. Consistent with a previous study, no differences in AST levels were observed [17]. These biochemical alterations underscore ongoing liver damage and fibrotic progression associated with oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, cytokeratins, and Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) suggest extensive hepatic cell injury, altered cellular permeability, and leakage of liver enzymes such as ALT and ALP into the bloodstream. This reflects the compromised structural integrity of the hepatocytes and necrotic processes in the liver. Treatment with UC-MSCs+SEVs effectively mitigated these biochemical disruptions, as evidenced by a significant reduction in serum ALP activity at weeks 6 and 8 and ALT levels at week 8 in the treated group (Figures 4D and E). This normalization of hepatic enzymes underscores the reduction in fibrotic progression, decreased hepatocellular stress, and the restoration of liver function. These findings highlight the hepatoprotective and antifibrotic properties of UC-MSCs+SEVs.

Antioxidant parameters: Elevated levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide contribute to lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage, ultimately leading to cellular damage. In the present study, the administration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in conjunction with exosomes to animals was associated with increased levels of antioxidants, including Glutathione (GSH) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx), as depicted in Figures 4F and G. Furthermore, the antioxidant biomarkers Glutathione (GSH) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx), which were depleted in fibrotic rats, exhibited significant recovery in treated animals (GSH: p<0.01; GPx: p<0.001; Figures 4F and G). This enhancement of antioxidant defenses aids in restoring the balance between oxidants and antioxidants and potentially plays a crucial role in promoting liver regeneration by mitigating oxidative stress and protecting cellular integrity.

Figure 4: Hematological analysis was conducted to assess changes in (A) Differential cell count, (B) Platelet Distribution Width (PDW), and (C) Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) of blood samples. Biochemical analysis evaluated alterations in (D) Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and (E) Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) levels in serum samples between the disease control and treatment groups. Antioxidant levels were compared in (F) Glutathione (GSH) and (G) Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) through antioxidant assays of liver tissue in both the disease control and treatment groups. The results are presented as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). Statistical significance for the treatment group (n=14) is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 when compared to the disease control group (n=8); ns denotes non-significant differences.

Impact of UC-MSCs+SEVs on mRNA expression levels in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

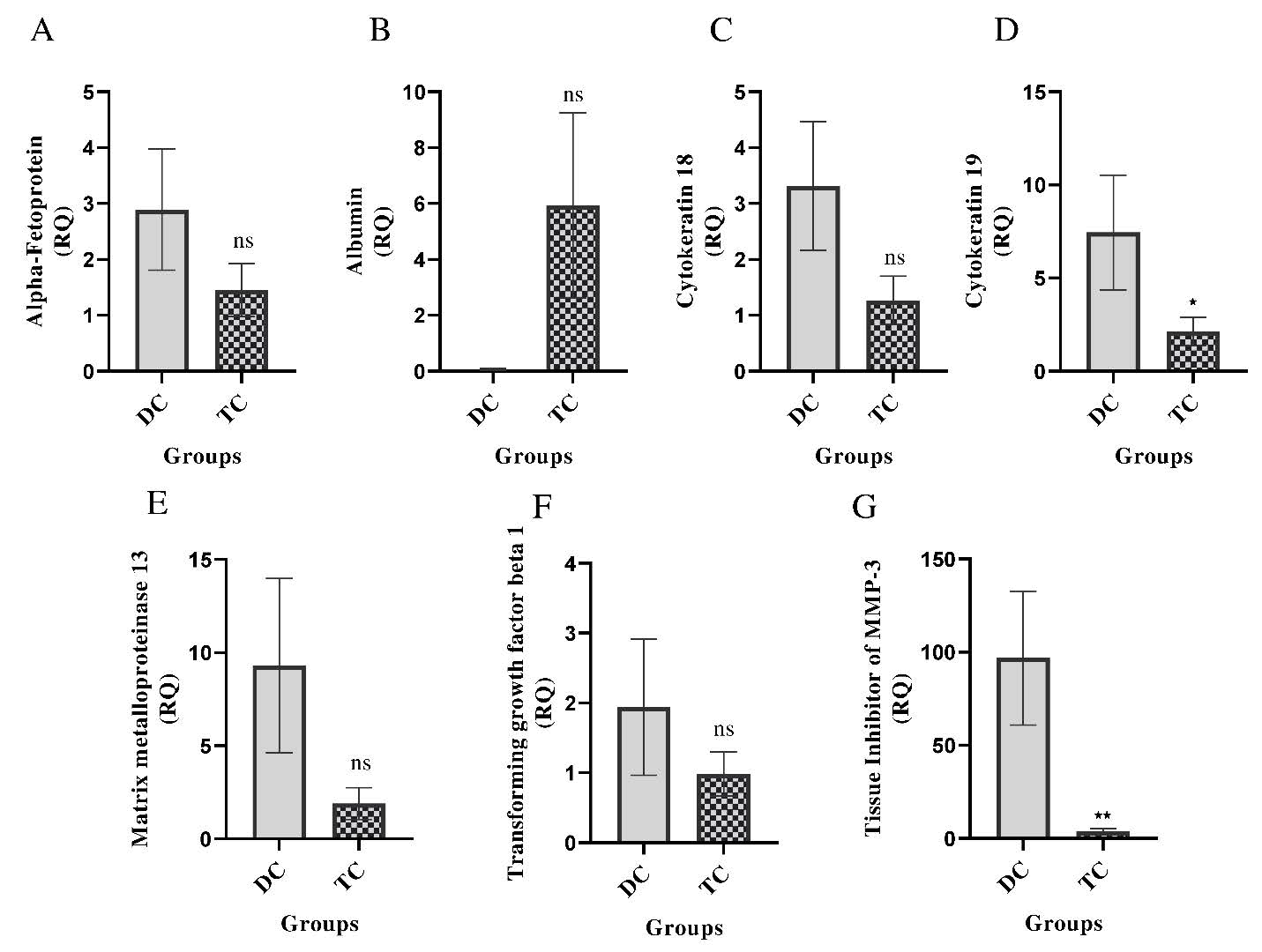

Reversal of fibrogenic and hepatocellular gene expression: To further evaluate the therapeutic effects of UC-MSCs in combination with SEVs on liver fibrosis, RT-PCR was performed to assess the mRNA expression of key hepatic markers in CCl4-treated rats. In the disease group, there was a significant upregulation of fibrogenic and injury-related genes, including α-Fetoprotein (AFP), Cytokeratin-18 (CK-18), Cytokeratin-19 (CK-19), Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13),Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3), And Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1), indicating liver injury, regeneration, and fibrotic progression (Figures 5A, C–G). In contrast, Albumin (ALB) expression was also suppressed (Figure 5B). Treatment with UCMSCs+ SEVs resulted in a significant downregulation of CK-19 (p<0.05) and TIMP-3 (p<0.01), suggesting a reduction in hepatocyte dedifferentiation and fibrogenic signaling. Although AFP, CK-18, MMP-13, and TGF-β1 exhibited non-significant reductions, their decreased expression suggests suppressed fibrogenesis and hepatocellular stress. Notably, ALB levels showed a non-significant increase, implying partial functional recovery (Figures 5A–G). These findings demonstrated that UC-MSCs+SEVs effectively restored hepatic gene expression patterns and mitigated fibrotic progression by modulating key markers of liver injury and fibrosis. The significant reduction in CK-19 and TIMP-3 levels, along with trends towards normalization in other genes, underscores their hepatoprotective and anti-fibrotic potential in CCl4-induced liver damage.

Figure 5: Gene expression levels of various proteins in liver tissue were compared between the disease control and treatment groups. The proteins analyzed included: (A) Alpha-fetoprotein, (B) Albumin, (C) Cytokeratin-18, (D) Cytokeratin-19, (E) Matrix metalloproteinase-13, (F) Transforming growth factor-β1, and (G) Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3). The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance in the treatment group (n=14) is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 when compared to the disease control group (n=8); ns denotes non-significance.

Impact of UC-MSCs+SEVs on protein expression in CCl4- induced liver fibrosis

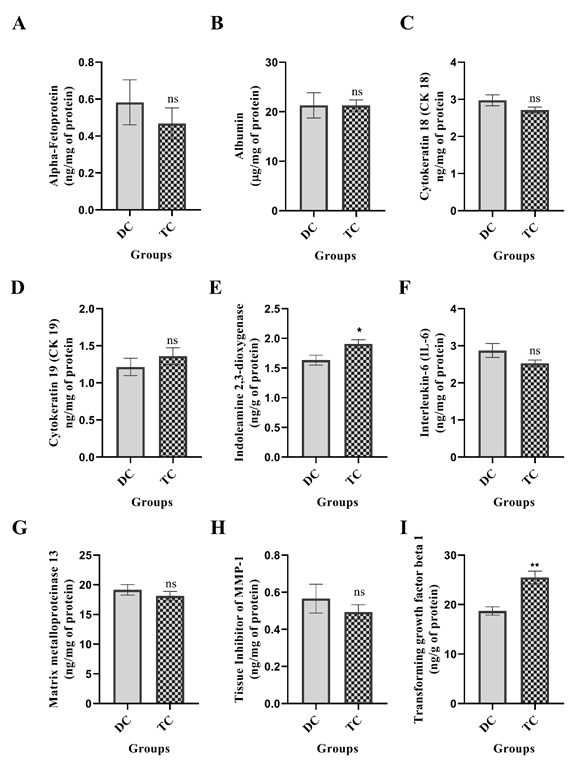

Modulation of protein biomarkers by ELISA: The therapeutic efficacy of UC-MSCs in conjunction with SEVs in mitigating CCl4- induced liver fibrosis was evaluated using ELISA-based quantification of protein expression in hepatic tissues (Figure 6). The fibrotic control group exhibited significant dysregulation of protein markers with notable reductions in indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO; p<0.05) and Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1; p<0.01). Although the changes in the levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), albumin (ALB), cytokeratin-18 (CK-18), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13), and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) were not statistically significant. Conversely, a slight but nonsignificant reduction was observed for Cytokeratin-19 (CK-19). These molecular alterations suggest that significant liver damage is likely to be driven by oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to hepatocyte membrane disruption, protein leakage, and impaired liver function.

Figure 6: The expression levels of various protein markers in liver tissues from disease control and treatment groups were assessed using ELISA. The markers evaluated included (A) Alpha-fetoprotein, (B) Albumin, (C) Cytokeratin-18, (D) Cytokeratin-19, (E) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, (F) Interleukin-6, (G) Matrix metalloproteinase-13, (H) Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), and (I) Transforming growth factor-β1. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance for the treatment group (n=14) is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 when compared to the disease control group (n=8); ns denotes non-significant differences.

Administration of UC-MSCs in combination with SEVs significantly ameliorated these pathological changes. Restoration of IDO and TGF-β1 expression levels, along with a reduction in proinflammatory and fibrotic mediators, indicates a robust therapeutic effect. This recovery underscores the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic potential of the combined therapy, possibly mediated through the modulation of the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway. Collectively, these findings suggest that UC-MSCs and SEVs synergistically protect hepatocytes, reduce fibrosis, and enhance the overall liver architecture and function.

Impact of UC-MSCs+SEVs on histop aapthpoelaorgaincacel of Cirrhosis in CClâ??-induced liver damage

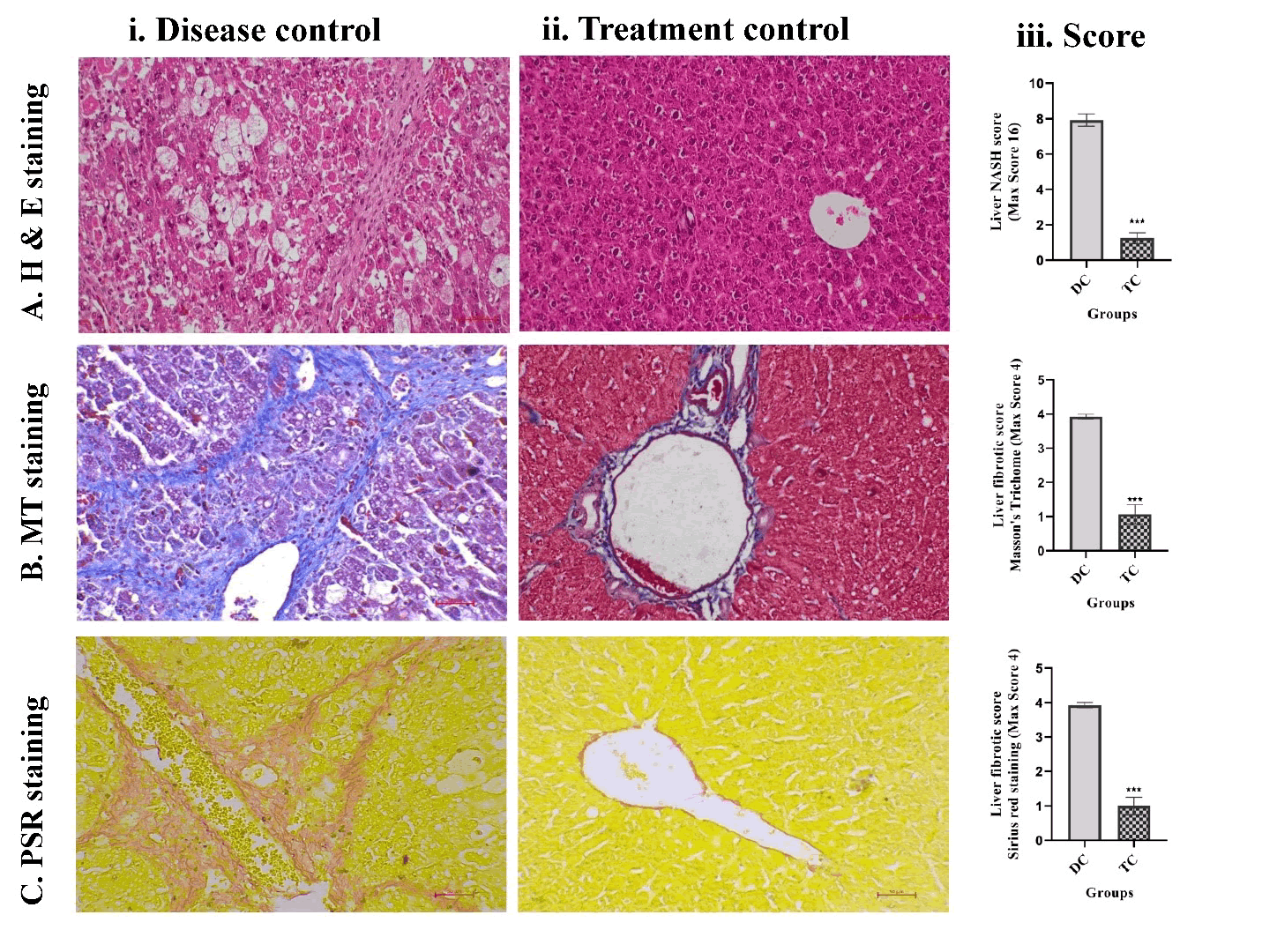

Histopathological improvement in liver architecture: Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis were evaluated using a combination of histological techniques, including Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Masson's Trichrome (MT), and Picrosirius Red (PSR) staining. These staining methods consistently revealed similar histopathological patterns across the groups. Repeated administration of CCl4 in olive oil over a six-week period resulted in severe liver damage, with qualitative assessments by an experienced pathologist confirming extensive fibrosis and cirrhosis. Representative micrographs (Figure 7) illustrate the pronounced morphological differences between the untreated fibrotic controls and treated animals.

Histological analysis revealed significant hepatic injury in the disease control group, characterized by architectural distortion, bridging fibrosis, dense collagen accumulation, and strong birefringence under polarized light (Figures 7A-C). Among these, 12 of the 14 animals developed histologically confirmed cirrhosis (p<0.001). In contrast, none of the animals that received UC-MSCs or SEVs developed cirrhosis, indicating a significant reversal of the disease. Notably, only 2 of the 14 animals in the disease group exhibited spontaneous resolution of cirrhosis.

Three weeks after treatment with UC-MSCs and SEVs, liver tissues demonstrated marked structural improvements. Histological features showed restoration of normal lobular architecture, a significant reduction in necroinflammation, and decreased collagen content. Fibrosis and NASH activity scores were significantly lower in the treated group than in the disease control group (p< 0.001; Figures 7A-C).

Overall, CCl4-induced fibrotic and cirrhotic livers exhibited severe tissue remodeling, including thick fibrous septa, pseudolobule formation, and widespread collagen deposition. These pathological hallmarks were substantially reversed following the combined UCMSC and SEV therapy. H&E, MT, and PSR staining collectively demonstrated significant histological recovery, which was further validated by quantitative fibrosis scoring. The treatment resulted in a highly significant reduction in fibrotic indices (p<0.001), confirming the robust antifibrotic efficacy of UC-MSCs and SEVs.

Figure 7: Histopathological staining techniques, including (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin, (B) Masson's Trichrome , and Picrosirius Red (PSR), were employed to analyze (i) Liver tissues from disease control and (ii) Treatment groups, as well as (iii) Histopathological scores, specifically for Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and fibrosis. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance for the treatment group (n=14) compared to the disease control group (n=8) is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001; ns denotes non-significant differences.

Effect of UC-MSCs+SEVs on IHC markers in the liver tissue

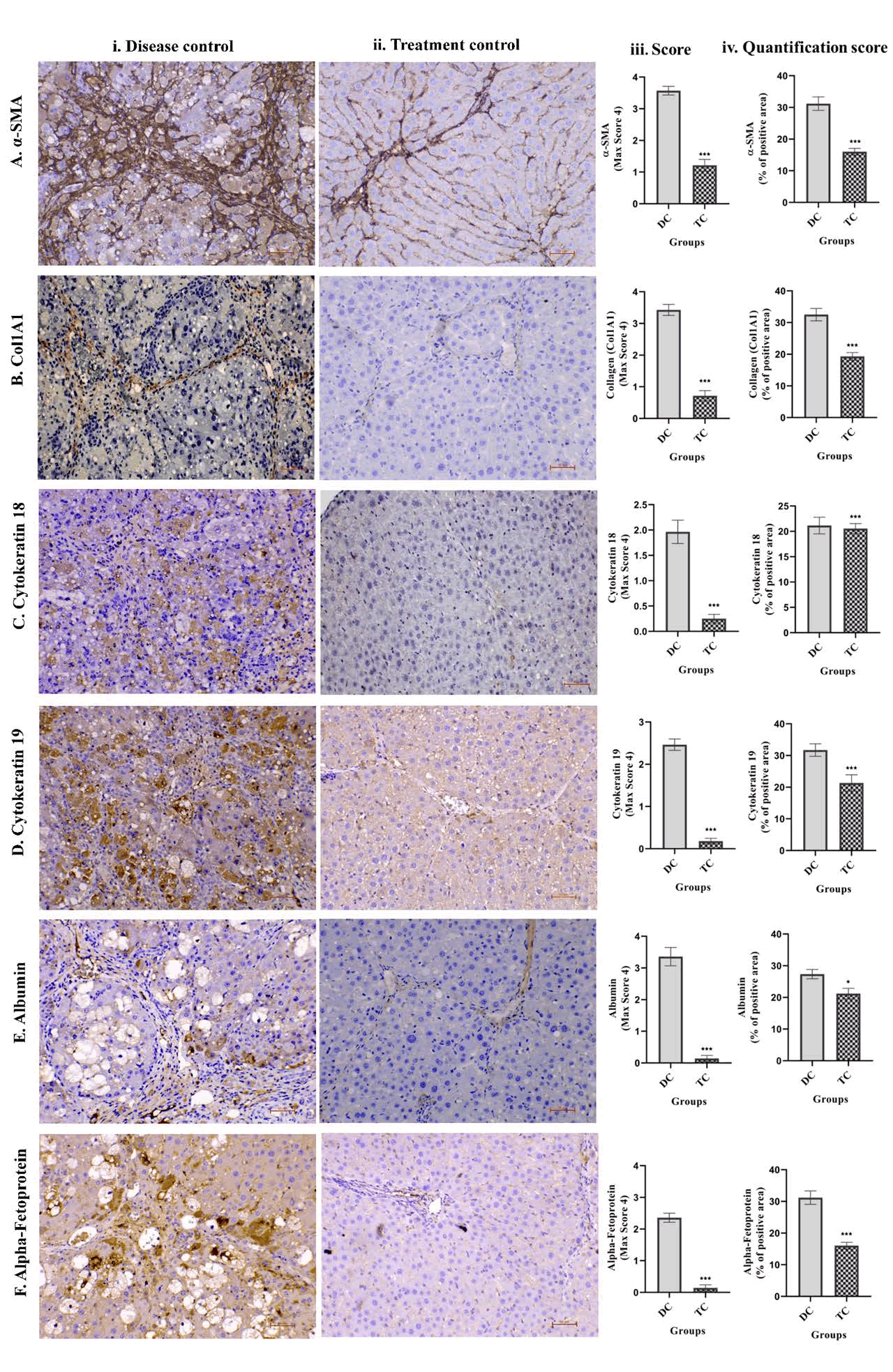

Reduced expression of fibrotic and dedifferentiation markers by immunohistochemistry: Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to evaluate the expression of key hepatic and fibrotic markers, α-SMA, COL1A1, ALB, AFP, CK-18, and CK-19, to assess the effects of UCMSCs combined with SEVs on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Six weeks of CCl4 administration with olive oil resulted in severe liver damage, characterized by architectural disarray, prominent fibrous septa, pseudolobular formation, and extensive collagen accumulation. These pathological changes were confirmed through qualitative pathological assessment and quantitative image analysis using the FIJI software (Figure 8).

The disease group exhibited pronounced upregulation of α-SMA and COL1A1, indicating activation of hepatic stellate cells and excessive Extracellular Matrix (ECM) deposition, respectively (Figures 8A). In contrast, animals treated with UC-MSCs and SEVs demonstrated a significant downregulation of both markers (p<0.001, Figures 8A), reflecting reduced fibrogenic activity and ECM remodeling.

Albumin (ALB), a marker of hepatocyte function, was notably diminished (p<0.05) in fibrotic livers, but was significantly restored (p<0.05) following UC-MSC+SEV therapy (Figure 8E), indicating recovery of hepatocyte functionality. Similarly, elevated expression of α-Fetoprotein (AFP), Cytokeratin-18 (CK-18), and Cytokeratin-19 (CK-19), indicative of hepatocyte dedifferentiation and the acquisition of a progenitor-like phenotype, was markedly reduced after treatment (p<0.001, Figure 8F, C-D). This normalization suggests reversal of liver injury and restoration of mature hepatocyte identity.

Weekly administration of UC-MSCs and SEVs for three weeks led to substantial histological improvement and normalization of IHC markers (p<0.001 for α-SMA, COL1A1, AFP, CK-18, and CK-19; p<0.05 for ALB). These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in fibrosis scores and reversal of cirrhosis in treated animals, as validated by pathological scoring.

Overall, this comprehensive IHC analysis underscores the robust therapeutic efficacy of UC-MSCs combined with SEVs in mitigating liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. This treatment effectively modulated fibrogenic and hepatic markers, restored liver architecture, and reestablished functional hepatocyte populations, highlighting its potential as a regenerative strategy for chronic liver injury.

Figure 8: Immunohistochemical analysis was conducted on (A) α- SMA, (B) COL1A1, (C) Cytokeratin 18, (D) Cytokeratin 19, (E) Albumin, and (F) Alpha-Fetoprotein in liver tissues from (i) disease control and (ii) treatment animal groups. Additionally, (iii) IHC scores and (iv) quantitative scores representing the percentage of positive area were determined using Fiji Software. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance for the treatment group (n=14) compared to the disease control group (n=8) is indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001; ns denotes non-significant differences.

Effect of UC-MSC and SEV therapy improves survival

Survival analysis: A 45-day survival analysis indicated that untreated fibrotic rats administered CCl4 exhibited a mortality rate of 42.8%, whereas no fatalities were observed in the treatment group. Mortality was restricted to the disease control group, with one animal succumbing in the second week and the other five succumbing in the fifth week. By contrast, the group treated with UC-MSCs+SEVs demonstrated complete survival until the conclusion of the experiment. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a significant difference in survival outcomes: The control group experienced 42.8% mortality, primarily between weeks 2 and 5 (Figure 3B), whereas the treated group had no fatalities (p<0.01).

Discussion

Numerous animal trials have established that MSCs and exosomes, when used separately, are safe and effective in alleviating liver failure [11,18]. Although animal trials have shown promising results for exosomes in liver failure [11] there are currently no published human trials on exosomes. However, MSCs have shown promising results in numerous animal and clinical trials on liver failure [8]. To date, no trial has explored the potential synergistic effects of combining these two biologics to enhance therapeutic outcomes, not only in liver failure but also in any disease condition, either in pre-clinical or clinical trials. Our trial demonstrated that the combined use of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and exosomes can facilitate hepatic regeneration, leading to the reversal of fibrosis and cirrhosis, as well as improvements in liver function, morbidity, and mortality.

Importantly, the reversal of cirrhosis was also observed in this study, as 12/14 animals in the control group exhibited cirrhosis, which was not observed in any of the treated animals. Histopathological evaluation using PSR, MT, and H&E staining demonstrated near-complete resolution of fibrosis and cirrhosis in treated animals, consistent with previous MSC and exosome animal trials [17,19-21]. This marked reversal has not been previously reported with non-biological treatments, highlighting the potential for further investigation.

Remarkably, in contrast to the control group, gross examination of the livers in the study cohort revealed a significant reversal of fibrosis in the treated animals, whose appearance closely resembled that of the normal livers. These beneficial effects have been reported in animal trials using biologics [17,19-21], which is unprecedented for other non-biological pharmacological agents.

All animals that received CCl4 exhibited abnormal responses to handheld stimulation, displaying signs of irritability and resistance to touch, particularly in the abdominal region, which is indicative of pain and tenderness. Additionally, decreased motility and increased anxiety were observed in the CCl4-treated animals. Notably, these adverse effects were reversed in the animals treated with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) or exosomes. Furthermore, CCl4-treated animals displayed lethargy, reduced food intake, progressive body weight loss, elevated liver weight index, and increased liver weight, all of which were improved in the treatment group.

In response to noxious stimuli, Kupffer cells release TGF-β, which subsequently transforms stellate cells into myofibroblasts, stimulates Extracellular Matrix (ECM) production, predominantly collagen, and culminates in fibrosis. Upon ACTA2 activation, myofibroblasts express α-SMA, a well-known fibrosis marker. Additionally, during liver injury, HSCs are activated in response to TGF-β and are a major source of COL1A1, resulting in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. MSCs in combination with exosomes facilitated a reduction in α-SMA levels and COL1A1 by IHC staining in treated animals, indicating decreased HSC activation and myofibroblast activity with subsequent reversal of fibrosis. Furthermore, H&E, MT, and PSR staining demonstrated significant reversal of fibrosis and cirrhosis in the treatment group. Taken together, the decrease in α-SMA and COL1A1 levels and resolution of fibrosis/cirrhosis based on immunohistology seem to indicate that the combination of MSCs and exosomes can be potentially antifibrotic.

CK19 expression indicates the activation of hepatic progenitor cells in response to chronic liver damage or diseases, such as hepatitis or cirrhosis. A reduction in CK19 mRNA expression by liver cells and in the immunohistochemistry score was noted in the treatment group, implying possible liver regeneration. When hepatocytes undergo apoptosis or necrosis owing to liver injury, CK18 is cleaved by caspases and released. However, the mRNA expression and immunohistochemistry scores of CK-18 were reduced in the treated animals, reflecting liver rejuvenation. Elevated ALT levels are primarily associated with hepatocellular injury as they are predominantly found in the liver. When liver cells are damaged, ALT is released into the bloodstream, making it a critical marker for the assessment of liver health. ALP levels may correlate with liver disease severity, particularly in conditions characterized by cholestasis. Persistent elevation of ALP can indicate worsening of liver function or progression to more severe forms of liver disease such as cirrhosis. Decreases in ALT and ALP levels were observed in the animals in the treatment group. The reduction in CK-18, CK-19, ALT, and ALP levels indicated the possible hepatoprotective effects of the MSCexosome combination. The non-significant increase in albumin mRNA expression in treated animals suggests restoration of hepatic function.

Increased levels of IDO were observed in the liver tissues of the treated animals. IDO catalyzes the first rate-limiting step in the catabolism of tryptophan to kynurenine, which in turn decreases the activity of T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells while stimulating Tregs, thereby modulating the inflammatory response observed in chronic liver failure. Decreases in elevated neutrophil, monocyte, basophil, and eosinophil counts, along with an increase in depressed lymphocyte counts in the treatment group, may reflect the leveling of the immune and inflammatory responses associated with progressive liver fibrosis.

Oxidant/antioxidant imbalance is a critical factor implicated in tissue injury across a wide range of diseases. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) are recognized for their express various antioxidant enzymes, which can help restore the balance. Notably, our study revealed significant elevations in key antioxidant enzymes [21,22], including Glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), in the liver tissues of treated animals. This increase in antioxidant activity may have contributed to the observed liver regeneration, suggesting a potential therapeutic role of MSCs in mitigating oxidative stress and promoting tissue repair.

The exclusive administration of MSCs has been shown to have beneficial effects in controlled trials involving CCl4-induced liver injury in animal models. Studies have reported positive outcomes for exosomes in comparable settings, indicating that both MSCs and exosomes have independent therapeutic benefits [23]. A survival benefit was demonstrated in a previous study using MSCs [23], larger doses were required than those used in the present study. In a rat model of CCl4 induced liver failure, portal vein infusion and hepatic parenchymal injection of 1 million autologous adipose MSCs without exosomes resulted in hepatic regeneration. However, the survival benefit was not assessed. Although improvements in total bilirubin levels and sonographic and histopathological appearances were noted five weeks after MSC treatment, no improvement in survival was reported despite the invasive mode of MSC administration [17]. The primary objective of any therapeutic agent is to reduce the morbidity and mortality. Although morbidity rates have been found to be comparable when MSCs and exosomes are administered independently in animal models of chronic liver disease, the combination of these two biologics appears to enhance survival rates compared with MSC treatment alone.

Unexpectedly, we observed a survival benefit in the present study. This could be attributed to the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis, restoration of the hepatic architecture, and rejuvenation of hepatocyte morphology associated with functional improvement. In the control group, 42% of the animals succumbed to CCl4-induced injury, whereas none of the animals in the treatment group died. Although the results of animal trials cannot be translated directly into clinical trials, this finding is particularly significant, given that liver diseases account for approximately 2 million deaths annually (4% of all global deaths), with cirrhosis contributing to half of these fatalities. Although numerous animal trials have demonstrated hepatic regeneration following MSC administration [17,19,20-22,24,25] in chronic liver disease, and only one trial has assessed its survival benefits. Yu et al. administered low, medium, and high MSC doses of 2.5, 5, and 10 million GMP grade UC-MSCs IV, respectively, in a CCl4 liver injury mouse model. The survival rates for high, medium, and low doses were 100%, 92.3%, and 90.7%, respectively, whereas those for the control group were only 55% in the control group [23]. Although the survival benefit in this study was comparable to that in our trial, larger doses were required compared to our study. In contrast to the severe combined immunodeficiency (SOD) mice used in their study, our animals were not immunocompromised. The primary objective of any therapeutic agent is to reduce the morbidity and mortality. Although morbidity rates have been found to be comparable when MSCs and exosomes are administered independently in animal models of chronic liver disease, the combination of these two biologics appears to enhance survival rates compared with MSC treatment alone [23-26].

Our study reveals several intriguing findings that warrant further investigation. Notably, Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) exhibited a pleiotropic effect, with decreased mRNA expression, in contrast to the increased levels detected by ELISA. As a cytokine secreted by Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), TGF-β is implicated in tissue regeneration via the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway [26], suggesting its potential role in liver regeneration, as observed in this study. TGF-β is also a primary driver of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Additionally, Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3), a crucial regulator of Extracellular Matrix (ECM) remodeling, showed significantly reduced mRNA expression in treated animals, which could exacerbate ECM degradation and contribute to liver disease progression. Furthermore, while albumin mRNA expression was elevated in the liver tissues of the treatment group, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed lower albumin levels, highlighting the complexity of these findings and the need for further exploration (Supplementary Figures).

This study successfully demonstrated the safety and efficacy of combining Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and exosomes for the treatment of chronic liver failure. However, they do not provide insights into the individual contributions of these components. To elucidate their distinct roles, future studies should incorporate multiple study arms to allow for comprehensive assessment of the specific therapeutic effects of MSCs and exosomes. This approach will enhance our understanding of the synergistic or independent mechanisms of action, ultimately leading to the development of targeted and effective therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion

Liver failure remains a critical global health issue and therapeutic interventions are scarce. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and exosomes have shown independent regenerative capabilities in preclinical studies of chronic liver disease. However, their therapeutic potential has not been explored. This study was the first to evaluate the effectiveness of MSCs and exosomes in reversing fibrosis and cirrhosis, restoring liver architecture, and enhancing morbidity and mortality in a CCl4-induce liver failure model. Combination therapy markedly improved survival rates compared with the control groups, with no mortality recorded among the treated subjects. Histopathological analysis demonstrated a nearly complete resolution of fibrosis, supported by decreased α-SMA and COL1A1 expression. Additionally, treatment with MSC-exosomes resulted in improved ALT and ALP levels, improved hepatocyte morphology, and restored immune balance, as indicated by increased IDO expression and normalized lymphocyte count. Elevated levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as Glutathione (GSH) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) suggest a protective effect against oxidative stress-related damage. Importantly, the reduced expression of CK-18 and CK-19 suggests their potential for liver regeneration. Although MSCs and exosomes individually offer hepatoprotective effects, their combined use appears to amplify the therapeutic outcomes. Given the remarkable fibrosis reversal and survival benefits observed, further research is necessary to elucidate the synergistic mechanisms of MSC-exosome interactions. Future clinical applications of this innovative therapeutic strategy could address the unmet needs of liver disease treatments.

Acknowledgement

All the authors gratefully acknowledge the technical staff for their valuable support in completing this project.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by Tulsi Therapeutics Private Limited.

Ethical Compliance

All experimental procedures were performed in strict accordance with the CCSEA guidelines, formerly called CPCSEA, Government of India, for the care and use of laboratory animals. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC of the University of Hyderabad, School of Life Sciences (Approval No. UH/IAEC/MS/21/03/2024/08.

Data Access Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study were stored securely and can be shared for academic and noncommercial purposes in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines. Any restrictions on data access (e.g., due to privacy or third-party agreements will be clearly communicated upon request.

Conflict of Interest declaration

SA, RB, MT, AV, and RG are associated with Tulsi Therapeutics Private Limited and declare no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. NC declare no conflicts of interest specific to this study. For full transparency, NC received consulting fees from Madrigal, GSK, Zydus, Altimmune, BioMea Fusion, Ipsen, Akero, Merck and Pfizer. He has also received research grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Exact Sciences. Additionally, he holds equity in Avant Sante, a contract research organization, and in Heligenics, a drug discovery startup.

Author Contributions

SA, NC, AD, and MG conceptualized the study and contributed to project administration, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, methodology, and validation. RB, SK, SR and MT were involved in the project administration, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, and validation. RG, AV, and SR contributed to visualization, writing, review, and editing of the manuscript.

References

- Ufere NN, Satapathy N, Philpotts L, Lai JC, Serper M (2022) Financial burden in adults with chronic liver disease: A scoping review. Liver Transpl 28: 1920-1935.

- Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL, Arrese M, et al. (2023) Global epidemiology of cirrhosis—aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 20: 388-398.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, et al. (2023) Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol 79: 516-537.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galipeau J, Sensébé L (2018) Mesenchymal stromal cells: Clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 22: 824-833.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimamura Y, Furuhashi K, Tanaka A, Karasawa M, Nozaki T, et al. (2022) Mesenchymal stem cells exert renoprotection via extracellular vesicle-mediated modulation of M2 macrophages and spleen-kidney network. Commun Biol 5: 753.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao Y, Ji C, Lu L (2020) Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis. Ann Transl Med 8: 562.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spees JL, Lee RH, Gregory CA (2016) Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res Ther 7: 1-13.

- Lu W, Qu J, Yan L, Tang X, Wang X, et al. (2023) Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther 14: 301.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welsh JA, Goberdhan DC, O'Driscoll L, Buzas EI, Blenkiron C, Bussolati B, et al. (2024) Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 13: e12404.

- Hessvik NP, Llorente A (2018) Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci 75: 193-208.

- Fang X, Gao F, Yao Q, Xu H, Yu J, et al. (2023) Pooled analysis of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicle therapy for liver disease in preclinical models. J Pers Med 13: 441.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Xiang B, Wang X, Xiang C (2017) Exosomes derived from human menstrual blood-derived stem cells alleviate fulminant hepatic failure. Stem Cell Res Ther 8: 1-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, et al. (2006) Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8: 315-317.

- Sangaraju R, Sinha SN, Mungamuri SK, Gouda B, Kumari S, et al. (2025) Effect of ethyl acetate extract of the whole plant Clerodendrum phlomidis on improving bleomycin (BLM)-induced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in rats: In vitro and in vivo research. Int Immunopharmacol 145: 113688.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, et al. (2005) Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41: 1313-1321.

- Chowdhury AB, Mehta KJ (2023) Liver biopsy for assessment of chronic liver diseases: A synopsis. Clin Exp Med 23: 273-285.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nazhvani FD, Haghani I, Nazhvani SD, Namazi F, Ghaderi A (2020) Regenerative effect of mesenteric fat stem cells on CCl4-induced liver cirrhosis, an experimental study. Ann Med Surg 60: 135-139.

- Wang X, Wang Y, Lu W, Qu J, Zhang Y, et al. (2024) Effectiveness and mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in preclinical animal models of hepatic fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 12: 1424253.

- Ghanem LY, Mansour IM, Abulata N, Akl MM, Demerdash ZA, et al. (2019) Liver macrophage depletion ameliorates the effect of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in a murine model of injured liver. Sci Rep 9: 35.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo XY, Meng XJ, Cao DC, Wang W, Zhou K, et al. (2019) Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells attenuates liver fibrosis in mice by regulating macrophage subtypes. Stem Cell Res Ther 10: 1-11.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang XY, Li PL, Tang J, Li ZL, Hao RC, et al. (2024) Generation and evaluation of human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells with antioxidant capacity. 32: 1888-1895.

- Jiang W, Tan Y, Cai M, Zhao T, Mao F, et al. (2018) Human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes suppress the development of CCl4-induced liver injury through antioxidant effect. Stem Cells Int 2018: 6079642.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Damania A, Jaiman D, Teotia AK, Kumar A (2018) Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosome-rich fractionated secretome confers a hepatoprotective effect in liver injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 9: 1-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang GZ, Sun HC, Zheng LB, Guo JB, Zhang XL (2017) In vivo hepatic differentiation potential of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Therapeutic effect on liver fibrosis/cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 23: 8152.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu H, Feng Y, Du W, Zhao M, Jia H, et al. (2022) Off-the-shelf GMP-grade UC-MSCs as therapeutic drugs for the amelioration of CCl4-induced acute-on-chronic liver failure in NOD-SCID mice. Int Immunopharmacol 113: 109408.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu X, Zheng L, Yuan Q, Zhen G, Crane JL, et al. (2018) Transforming growth factor-β in stem cells and tissue homeostasis. Bone Res 6: 2.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi