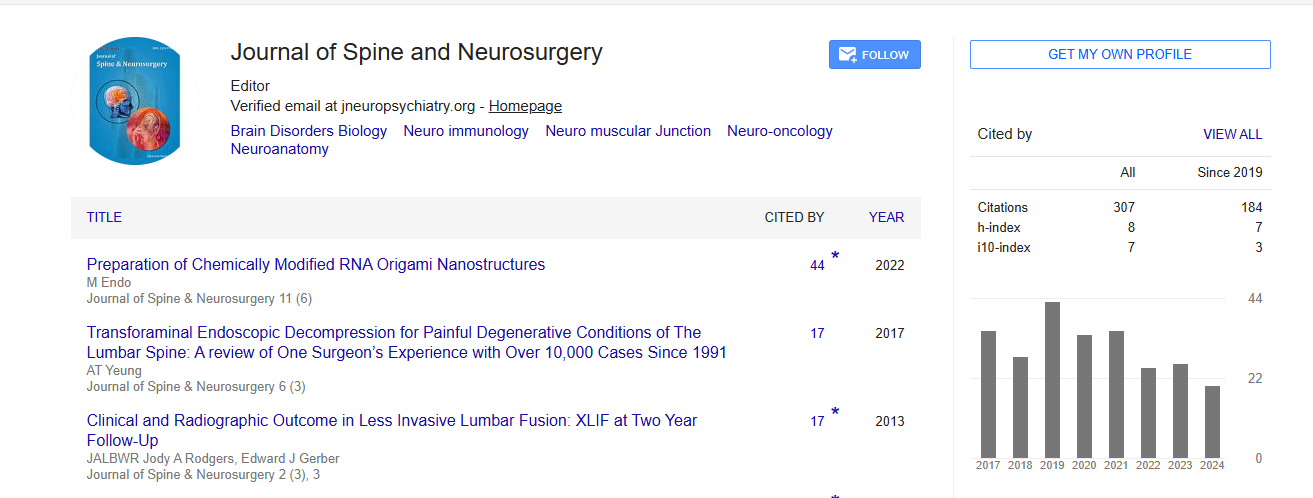

Editorial, J Spine Neurosurg Vol: 14 Issue: 3

LONG TERM EVALUATION OF LUMBAR SPINAL FUSIONS USING A CRYOPRESERVED VIABLE BONE ALLOGRAFT

John David Dorchak1* and J. Kenneth Burkus2

1Senior Spinal Surgeon, The Hughston Clinic, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Jack Hughston Memorial Hospital, 4401 River Chase Drive, Phenix City, Alabama 36867

2Research Associate, Hughston Foundation, Inc. 6262 Veterans Parkway, Columbus, Georgia 31908

*Corresponding Author:

- John David Dorchak

Senior Spinal Surgeon, The Hughston Clinic, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Jack Hughston Memorial Hospital, 4401 River Chase Drive, Phenix City, Alabama 36867

E-mail: jkb66@knology.net

Received: 01-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. jsns-25-169904, Editor assigned: 03- Sep-2025, PreQC No. jsns-25-169904(PQ), Reviewed: 17-Sep-2025, QC No. jsns-25-169904, Revised: 21-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. jsns-25-169904(R), Published: 29-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.4172/2325-9701.1000252

Citation: Dorchak JD, Burkus JK (2025) Long Term Evaluation of Lumbar Spinal Fusions Using a Cryopreserved Viable Bone Allograft. J Spine Neurosurg 14:252

Copyright: © 2025 John DD. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Cellular Bone Allografts (CBMs) contain osteogenic cell precursors and cytokines. Clinical and laboratory studies on CBMs and transplanted mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown variable success [1-4]. Dhaliwal [5] reported 21 patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion treated with CBMs. Twelve months following surgery, their fusion success rate was sixty-two percent and fusion failure rate of twenty-one percent. In a twenty-four-month follow-up study, Park [6] reported a fusion rate of over ninety-five percent. However, this prospective study did not use the CBM as a stand-alone implant. The CBM graft was augmented up to fifty percent with locally harvested autograft and/or cancellous allograft chips. With these results it is difficult to determine the exact role of the CBM versus the autograft and the autograft extenders. Kerr [7] showed a similarly high rate of interbody fusion using a CMB allograft. Fifty-two patients were enrolled in the study and followed for an average of fourteen months; a solid arthrodesis was achieved in over ninety-two percent of patients.

An optimized cryopreserved viable bone allograft has been developed that involves aseptic tissue processing and DMSO-free cryopreservation techniques that reliably preserve a viable endogenous cellular content. The retained living native cells including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and other osteoprogenitor cells are contained in the allograft through the non-cytotoxic preservation method [8]. These cellular bone allografts (CBMs) combine the inductivity of a demineralized bone matrix (DBM) with a bone derived cellular component [9]. This optimized CBM provides approximately 1.5 million cells per cc within an osteoconductive matrix. These CBMs have the potential to implant cellular lineages capable of osteoblastic activity at a surgical fusion site that support the osteogenic process of new bone formation [10,11]. This viable allograft tissue matrix provides components necessary for osteogenesis and has the potential to induce new bone formation in spinal surgeries.

A twelve-month short-term retrospective study of clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients undergoing lumbar interbody fusions (LIF) using this optimized CBM allograft has been published [12]. This current study continues the long-term evaluation of this initial cohort of patients (twenty-four to thirty-six months) and assesses the clinical and radiographic effectiveness of this advanced CBM allograft in patients with degenerative lumbar disc disease undergoing lumbar interbody fusion. We present this article in accordance with the TREND reporting checklist.

Material and Methods

A nonrandomized consecutive series of fourteen patients underwent single- or two-level lumbar interbody fusion (LIF) using a cellular allogeneic bone matrix as the sole bone graft material. A single investigator enrolled and operated on fourteen patients who had been treated at a single site between January 2022 and March 2025. Patients diagnosed with degenerative lumbar disc disease between L1 and the sacrum are included. All underwent an instrumented interbody fusion and received the optimized CBM (VIA Form+, VIVEX Biologics, Inc., Miami, FL) as a stand-alone bone graft replacement used with an interbody device.

The twelve-month outcomes of this fourteen-patient cohort have been reported [12]. Four patients were lost to follow-up after twelve months. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes were assessed in the remaining ten patients who were monitored for between twenty-four and thirty-six-months following surgery. Six patients were followed for twenty-four months and four were followed for thirty-six months. This study received IRB approval (HIRB-023-13).

Stand-alone bone graft substitute

In this clinical study, the optimized cryopreserved allograft was used as stand-alone graft without any additional autogenous grafts such as local bone or bone marrow aspirate. The CBM was composed of cancellous bone chips demineralized bone matrix and an endogenous cellular content [12,13].

The allograft is processed through a unique and propriety harvesting protocol. Following established aseptic techniques, donor bone is separated into two components: viable cell-rich cancellous bone and cortical bone. These cells attached to cancellous bone chips have been shown to express markers linked with those identified as mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts [8]. These endogenous live cells support the osteogenic process of new bone formation. The cell rich cancellous grafts are frozen and protected using a proprietary non-DMSO cryoprotectant [10]. This novel processing retains 1.5 million cells/cc with a 92% viability of cells. These preserved cells have demonstrated osteogenic potential that has been confirmed by in vitro assessment of alkaline phosphatase activity [14]. The cortical portion of the donor bone is demineralized to accentuate growth factors. Demineralized cortical bone fibers (DBM) provide surface features conducive for enhanced new bone formation. The DBM provides a topography for cell attachment and proliferation and eliminates the need for a carrier. The DBM has ideal porosity for cell migration and angiogenesis.

Inclusion criteria

All patients presented clinically with complaints of low back pain and radiating leg pain that was unresponsive to a minimum of eight weeks of nonoperative treatment that included immobilization, traction, modalities, medications, and physical therapy. In addition to recurrent or persistent complaints of back and/or leg pain, all patients had an objective neurologic deficit that included one or more of the following: an asymmetric deep tendon reflex, a sensory deficit in a dermatomal pattern, or motor weakness. All patients had plain radiographic findings documenting single- or two-level degenerative lumbar disc disease. In addition, each patient had a correlative neuroradiographic study that included an MRI scan. Patients with up to a Grade one spondylolisthesis were also included. Patient age, gender, smoking status, and comorbidities were assessed including the presence of diabetes, osteoporosis, and obesity. Patients were not included in this study if they had a chronic medical condition that required medication, such as steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications that could interfere with fusion.

Surgical technique

Patients with single- or two-level degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine and associated radiculopathy were treated by a posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) or extreme lateral interbody procedure (XLIF) using an interbody implant and posterior pedicle screw fixation. The CBM was used exclusively as a bone graft replacement. No autograft or other bone graft substitutes were used to supplement or expand the CBM. The CBM was placed in the disc space and in the intradiscal implant. Pedicle screws were inserted through a minimally invasive percutaneous technique. Following surgery, all patients were encouraged to ambulate immediately after surgery and physical activities were advanced at the discretion of the attending surgeon. An external lumbar orthosis was used at the preference of the attending surgeon.

Clinical and radiographic Follow-up

Patients were examined at three, six, twelve, twenty-four- and thirty-six months following surgery. Four patients were lost to follow-up after twelve months. All clinical outcomes were assessed by the attending physician. Clinical outcomes were not assessed through patient derived questionnaires. Neurological physical examination was conducted at each follow-up clinical visit. Neurological success was defined as maintenance or improvement in three objective clinical findings: sensory, motor, and reflex testing.

Neutral anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were obtained at each visit. Dynamic flexion-extension lateral radiographs were taken at six, twelve, twenty-four and thirty-six months. Segmental sagittal plane angulation was measured on neutral lateral radiographs and determined by Cobb’s criteria. Intradiscal distraction and subsidence was measured by assessing the vertical distance between the midpoints of the adjacent vertebral endplates. Intradiscal motion and implant migration were assessed from the dynamic radiographs. All radiographs were reviewed by an independent physician. A successful fusion was defined as demonstrating all of the following: 1. uninterrupted bridging bone across the instrumented disc space through either the interbody implants or around the implants, 2. radiolucent lines restricted to less than 50% at either implant at the host bone implant interface, and 3. less than 5° of angular motion and less than 3 mm of translation on dynamic flexion extension radiographs. Subsidence of the intradiscal implant and changes in segmental lordosis were also reviewed.

Adverse events

All patients were monitored for the presence of adverse events during the surgical procedure and during routine or unanticipated office visits. All complications were documented, including additional surgical procedures, spinal injections, and hospital readmissions.

Results

Patient demographics

This ten-patient cohort included five females and five males with an average age of 65 years ranging from 53 to 78 (Table 1). Three patients (3/10; 30%) smoked or used tobacco products; three (3/10; 30%) were obese with a BMI of greater than 30; two (2/10; 20%); were diabetic. None had osteoporosis. The choice of surgical implant or surgical approach was not correlated with co-morbidities nor the number of levels treated. There were seven single-level and three 2-level fusions between L1 and L5 (Tables 2 and 3).

| Sex | Male 5/10 Female 5/10 |

50% |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 53 – 78 years | (average) |

| Smokers | 3/10 | 30% |

| Diabetes | 2/10 | 20% |

| Obesity / BMI>30 | 3/10 | 30% |

| Osteoporosis / T-Score>2.5 | 0/10 | none |

| Lumbar Spinal Level | Frequency |

|---|---|

| L12 | 1 |

| L23 | 1 |

| L34 | 0 |

| L45 | 6 |

| L5 S1 | 5 |

| Total | 13 |

| Procedure | Level | Patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLIF | Single level | 5/10 | 50% |

| PLIF | Two level | 3/10 | 30% |

| XLIF | Single level | 2/10 | 20% |

Clinical outcomes

Ten patients in this long-term study cohort had a minimum follow-up of 24 months; four were followed out to thirty-six months. At the last follow-up examination, all patients had sustained improvement in back and leg pain symptoms when compared to their preoperative status. No standardized patient reported outcome questionnaires or numeric rating scale were used in these assessments. Neurological success was also seen in all study patients with none showing a loss in neurological functioning for the duration of the study.

Radiographic outcomes

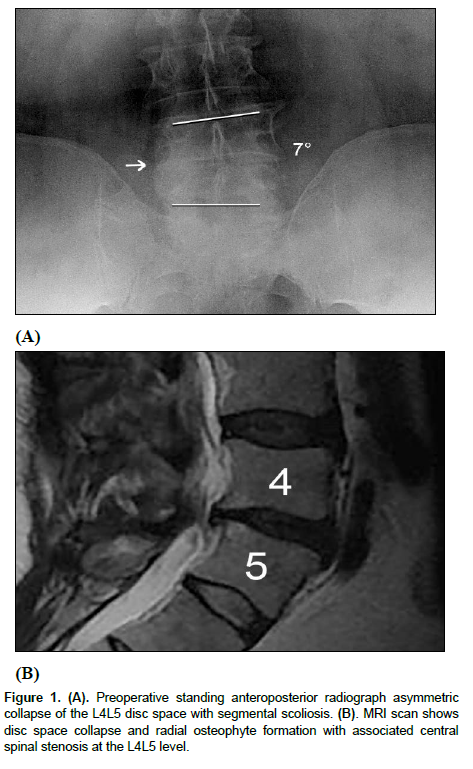

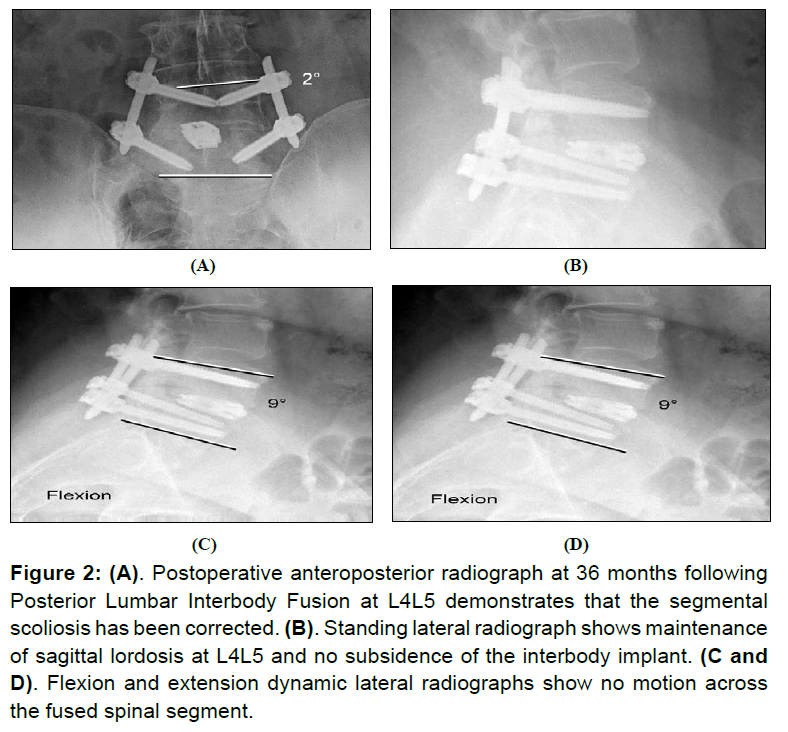

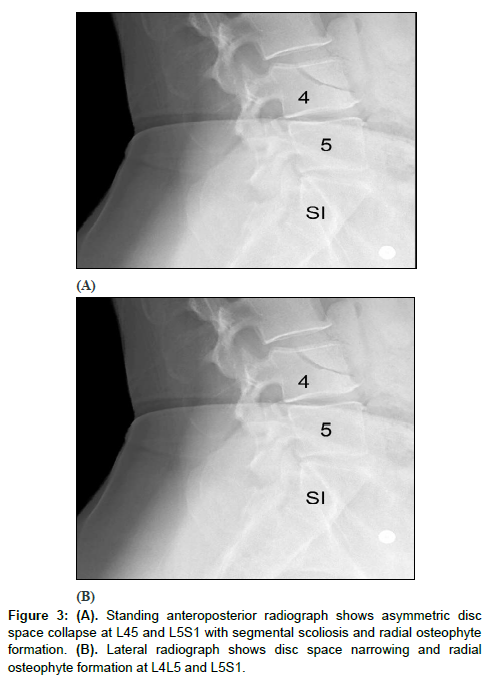

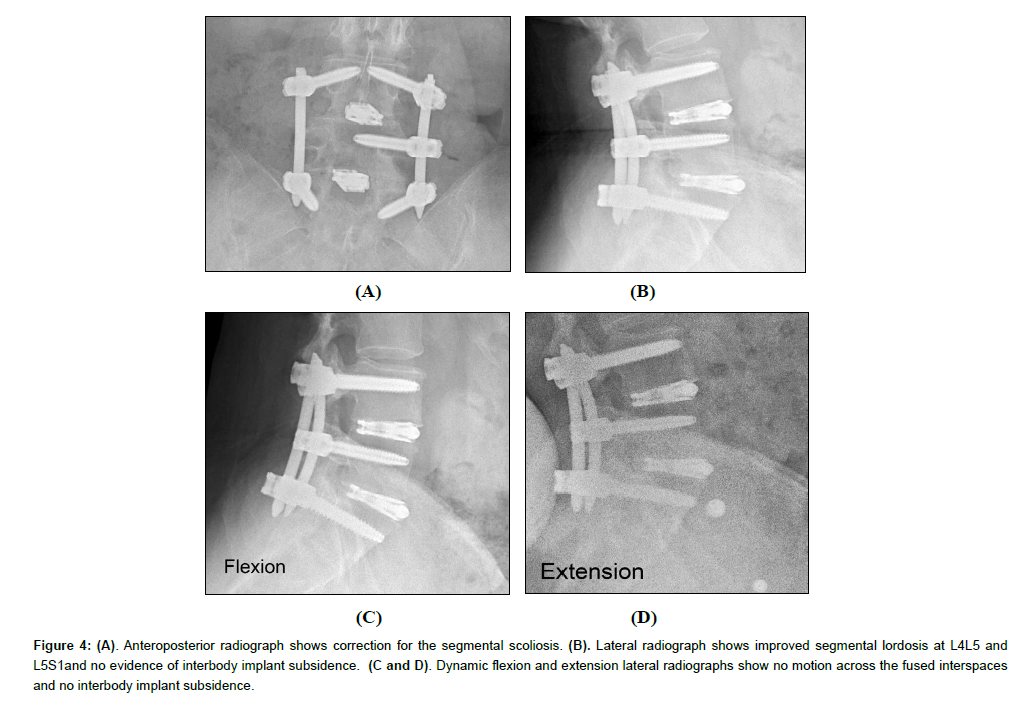

All patients showed successful radiographic fusion six months after surgery with evidence of bridging trabecular bone across the interspace forming a continuous bony connection from the superior vertebral body to the inferior vertebral body (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, there was no evidence of radiolucency involving more than 25% of the superior or inferior implant-vertebral interface. No patients had deterioration in their fusion status between the six-months and the last follow-up; all patients remained fused. There was no evidence of implant migration, subsidence, or loss of segmental lordosis at any disc level studied. There were no radiographic fusion differences in patients treated with one- or two-level fusion surgeries (Figure 3 and 4). Similarly, there were no differences in fusion outcomes regarding the PLIF or XLIF surgical approaches.

Figure 2: (A). Postoperative anteroposterior radiograph at 36 months following Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion at L4L5 demonstrates that the segmental scoliosis has been corrected. (B). Standing lateral radiograph shows maintenance of sagittal lordosis at L4L5 and no subsidence of the interbody implant. (C and D). Flexion and extension dynamic lateral radiographs show no motion across the fused spinal segment.

Figure 4: (A). Anteroposterior radiograph shows correction for the segmental scoliosis. (B). Lateral radiograph shows improved segmental lordosis at L4L5 and L5S1and no evidence of interbody implant subsidence. (C and D). Dynamic flexion and extension lateral radiographs show no motion across the fused interspaces and no interbody implant subsidence.

Adverse events

There were no complications associated with the use of the CBM as a bone graft substitute. No adverse events were identified at surgery or during the course of follow-up. No patients underwent any additional surgical procedures; none had revision of their supplemental posterior fixation. No patients had additional spinal injections. No patients sustained any loss of neurological function.

Discussion

Interbody fusion requires either osteogenic cells or osteoinductive signals to induce bone to form across the lumbar vertebral interspace. Autologous bone graft from the iliac crest has often been termed the “gold standard” as it contains osteogenic cells, cytokines and an osteoconductive matrix. Bone graft substitutes have been developed to avoid the complications and limitations associated with autologous iliac crest bone grafts (ICBGs) [15-19].

The composition of a cellular bone allograft similarly endows the graft with osteogenic cell precursors and cytokines. These viable MSCs closely resemble the natural cellular and biochemical profile of ICBG. The cell content offers the potential advantages of long-term cell proliferation, self-renewal capabilities, and multipotent differentiation. While clinical and laboratory studies on CBMs have shown variable success, this inconsistency may be related to the allograft harvesting, processing technique and the cryoprotectant chosen. Advanced processing methods for allograft stem cells are essential to enable the retention of regenerative potential for CBMs. Outside of the cellular component, the surface characteristics of the DBM (particulate vs fiber) and the percentage of the product that is fully demineralized influences the CBM’s osteogenic capability. In addition, the size cortical bone component and the presence of carriers affect the osteogenic potential of the CBM.

This report is a long-term follow-up of the use of a CBM allograft used as a stand-alone ICBM replacement for lumbar interbody fusions. In this study, all patients showed radiographic evidence of fusion at six months after surgery. There was no evidence of implant migration or hardware failure on postoperative radiographs in any patient throughout the duration of the study. Patients improved with their clinical symptoms and back and leg pain. None underwent any additional surgical procedures. This long-term retrospective study demonstrates that advanced CBMs can promote consistent fusions across the lumbar interspace. In addition, the deleterious effects of smoking, diabetes, osteoporosis, and obesity on rates of fusion may be overcome by utilizing this grafting material.

Study limitations

There are several limitations associated with this retrospective study. The study was not randomized nor controlled by comparing operative patients with patients treated nonoperatively or with a control arm (fusion without cellular allograft). In the initial treated cohort of fourteen patients, clinical and radiographic outcomes were conducted out to only twelve months. Ten of the fourteen enrolled patients have now been followed past twenty-four months. Clinical outcomes were not assessed through established patient derived questionnaires. Radiographic assessment of lumbar spinal fusion with standing and flexion-extension radiographs may not identify all pseudarthroses. Thin cut CT scans of the interbody fusions were not utilized.

Conclusion

These cellular allografts possess osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties and can be used as a stand-alone bone replacement in spinal fusion surgery. This cryopreserved viable bone allograft contains a heterogeneous population of cells that have the capacity for self-renewal and osteogenic differentiation. This unique allograft tissue represents a promising alternative to autologous ICBG in the surgical treatment of degenerative lumbar disc disease. Autogenous bone grafting and the morbidities and complications associated with this second surgery may be eliminated with this allograft technology.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Hughston Foundation for their assistance in medical illustrations and manuscript editing.

Author Contributions

JDD and JKB participated in the conception and design of the study; and participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data for the work. Additionally, both authors participated in drafting the article or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content. Finally, both authors gave the final approval of the version to be published; and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Gao Y, Li J, Cui H, Zhang F, Sun Y et al. (2019) Comparison of intervertebral fusion rates of different bone graft materials in extreme lateral interbody fusion. Medicine (Baltimore) 98: 17685.

- Lee DD, Kim JY (2017) A comparison of radiographic and clinical outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody fusion performed with either a cellular bone allograft containing multipotent adult progenitor cells or recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Orthop Surg Res 12: 126.

- Tally WC, Temple HT, Subhawong TY, Ganey T (2018) Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with viable allograft: 75 consecutive cases at 12-month follow-up. Int J Spine Surg 12: 76-84.

- Tohmeh AG, Watson B, Tohmeh M, Zielinski XJ (2012) Allograft cellular bone matrix in extreme lateral interbody fusion: preliminary radiographic and clinical outcomes. Scientific World Journal 263637.

- Dhaliwal J, Weinberg JH, Ritchey N, Akhter A, Gibbs D et al. (2025) A prospective evaluation of cellular bone matrix for posterolateral lumbar fusion. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 249: 1-9.

- Park DK, Wind JJ, Lansford T, Nunley P, Peppers TA et al. (2023) Twenty-four-month interim results from a prospective, single-arm clinical trial evaluating the performance and safety of cellular bone allograft in patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24: 895.

- Kerr EJ 3rd, Jawahar A, Wooten T, Ray S, Cavanaugh DA et al. (2011) The use of osteo-conductive stem-cells allograft in lumbar interbody fusion procedures: an alternative to recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein. J Surg Orthop Adv 20: 193-197.

- Martin WB, Sicard R, Namin SM, Ganey T (2019) Methods of cry protectant preservation: allogeneic cellular bone grafts and potential effects. Biomed Res Int 2019: 5025398.

- Majors AK, Boehm CA, Nitto H, Midura RJ, Muschler GF (1997) Characterization of human bone marrow stromal cells with respect to osteoblastic differentiation. J Orthop Res 15: 546-557.

- Malinin TI, Carpenter EM, Temple HT (2007) Particulate bone allograft incorporation in regeneration of osseous defects; importance of particle sizes. Open Orthop J 1: 19-24.

- LoGuidice A, Houlihan A, Deans R (2016) Multipotent adult progenitor cells on an allograft scaffold facilitate the bone repair process. J Tissue Eng 7: 2041731416656148.

- Dorchak JD, Gantt ML, Burkus JK (2024) Lumbar spinal fusions using a novel cellular.

- Mathias PG Bostrom, Daniel A (2005) Seigerman bone matrix allograft. J Spine Neurosurgery 13: 1-5.

- Barbanti BG, Mazzoni E, Tognon M, Griffoni C, Manfrini M (2012) Human mesenchymal stem cells and biomaterials interaction: a promising synergy to improve spine fusion. Eur Spine J 21: S3-9.

- Data on File. (2021) VIVEX BIOLOGICS, INC.

- Banwart JC, Asher MA, Hassanein RS (1995) Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity, a statistical evaluation. Spine 20: 1055-1060.

- Fernyhough JC, Schimandle JJ, Weigel MC, Edwards CC, Levine AM (1992) Chronic donor site pain complicating bone graft harvesting from the posterior iliac crest for spinal fusion. Spine 17: 1474-1480.

- Younger EM, Chapman MW (1989) Morbidity at bone graft donor sites. J Orthop Trauma 3: 192-195.

- Kim DH, Rhim R, Li L, Martha J, Swaim BH et al. (2009) Prospective study of iliac crest bone graft harvest site pain and morbidity. Spine J 9: 886-892.

- Schwartz CE, Martha JF, Kowalski P, Wang DA, Bode R et al. (2009) Prospective evaluation of chronic pain associated with posterior autologous iliac crest bone graft harvest and its effect on postoperative outcome. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7: 49.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi