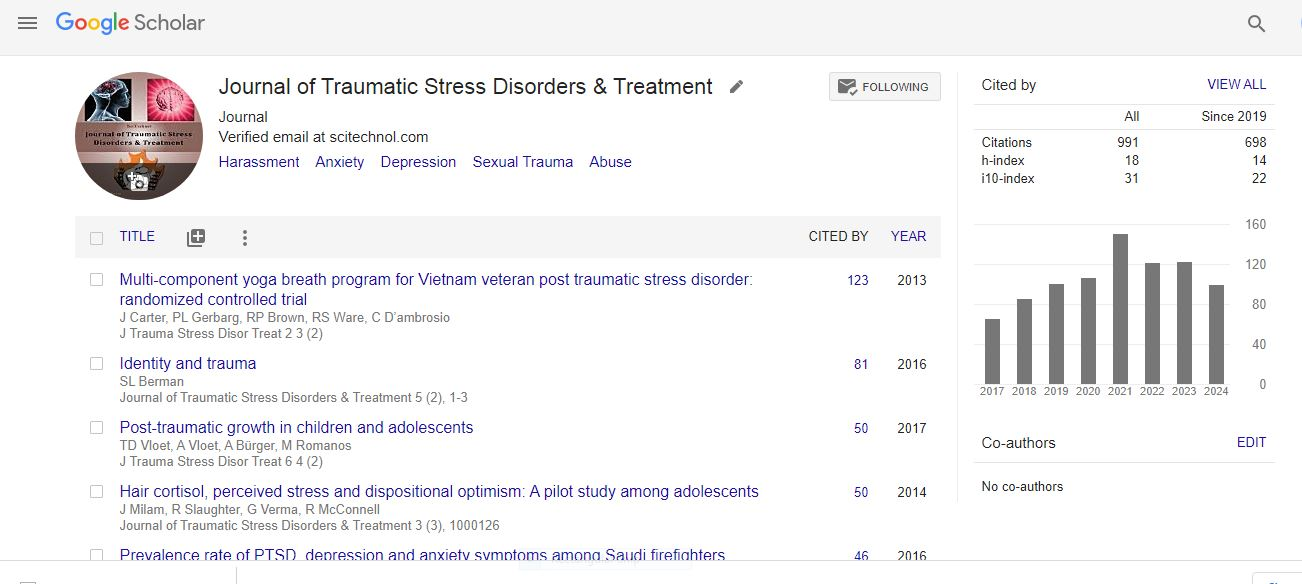

Review Article, J Trauma Stress Disor Treat Vol: 10 Issue: 2

Video Gaming Impact on Veteran Stress Disorders and Treatment: A Review

Maria Olenick*, Monica Flowers, Tatayana Maltseva, Ana Diez-Sampedro and Teresa Muñecas

Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA

*Corresponding Author:

Maria Olenick

Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing and Health Sciences

Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA

Tel: +1305-348-7757

Email: molenick@fiu.edu

Received: May 11, 2020 Accepted: February 11, 2021 Published: February 18, 2021

Citation: Olenick M, Flowers M, Maltseva T, Diez-Sampedro A, Muñecas T (2021) Video Gaming Impact on Veteran Stress Disorders and Treatment: A Review. J Trauma Stress Disor Treat 10:2.

Abstract

Video games have potential benefits for military personnel and veterans while abroad and at home. On deployment, gaming helps active military personnel decompress, eases the troubles of separating from family and friends, and builds a sense of community. At home, video games offer a way to escape posttraumatic experiences and deal with civilian reintegration. Video gaming presents an opportunity for military personnel and veterans to relieve traumatic stress and cope through comradery. Thus, it becomes important to understand veteran video gaming behavior and to optimize this modality to help with transitioning back to civilian life with the many veteran specific health sequelae deployments may have caused.

Keywords: Veterans, Military, Video, Gaming, Traumatic, Treatment

Keywords

Veterans, Military, Video, Gaming, Traumatic, Treatment

Introduction

Video games have rapidly become part of everyday lives in American families including active military, veterans and their families at home and abroad. Video games are forecast to hit $44.6 billion dollars in sales in the United States (U.S.) by the end of 2019 [1]. This is more than double the sales recorded by The NPD Group, Inc. (a leading market research company) in 2009. The video game industry has grown 20% a year over 2017 and 14% a year over 2018 [1]. Many services-separated veterans take video games as a hobby, while others may be self-managing an illness or chronic condition. Understanding veterans who game and potential modalities to incorporate video games into treatment, while mitigating negative effects, such as behaviors and desensitization to violence, becomes essential to help improve health behaviors and support the delivery of care and optimal wellness for military personnel, veterans, and their families [2].

Stress Relief, Coping and Comradery

U.S. military personnel generally have access to a variety of technologies, including computers, mobile phones, and tablets, for phone calls, email, texting, internet access, watching videos or television, and gaming [3,4]. During deployment, personnel report continued access to computers and tablets, but little to no mobile phone use, likely due to restrictions in war zones [4]. Though scant peerreviewed publications have examined the prevalence, motivations, or benefits of gaming specifically during deployment, reports in popular media suggest that gaming appears to offer military personnel a way to decompress and pass time while awaiting their next assignment. Gaming offers the opportunity for veterans, regardless of rank, to relieve stress, tension, and separation challenges while on deployment [5]. Gaming is reported to require requires “interactivity and a high level of engagement” [5] that helps military personnel unplug and take their mind off the anxiety of living in a combat zone. In a study by Banks and Cole [6], nearly half of military video game players said they had used video games to deal with challenges associated with their military service, with the two most commonly cited motivations for gaming involving recreation and coping. Similarly, the most commonly cited benefit of gaming, as expressed by military gamers, was social interaction and support [6]. Football, soccer, basketball, and hockey video games were among the most popular sold in September 2019 [1]. Instead of deployed service members focusing on how many days they have left of active duty, gaming gets them thinking about setting up an upcoming Madden or Call of Duty tournament with their battle buddies [7]. There are many organizations that provide supply crates filled with video gaming equipment to deployed troops, military hospitals, and/or bases stateside (e.g. Operation Supply Drop, Stack-Up). While some argue that first-person-shooter (FPS) games like Call of Duty may trigger flashbacks, reports suggest that playing FPS games is not predictive of PTSD symptoms, [8] and that veterans can find playing FPS help them navigate difficult PTSD symptoms [9]. More research is warranted in this area to help determine the specific types of FPS games, or situations within FPS games that may be problematic or beneficial for veterans’ mental health.

Once back home, many veterans continue to engage in video games as a mode of relaxation and decompression by disconnecting from their past traumatic experiences. Today’s veterans rely increasingly on digital technology to rehabilitate themselves when they return from combat. Video games seem to promote recovery in veterans in treatment for mental or behavioral health problems providing a “potent form of ‘personal medicine” that can help with recovery [10]. Ultimately, when gaming, they are generally playing in their place of residence and not engaging in self-destructive behavior (such as substance use).

A game console is not only a piece of entertainment technology, but a gateway to worlds that abide by certain rules and a way to melt away the (emotional and physical) stressors and distance between family and friends. A veteran stated that while playing video games with friends thousands of miles away that they would joke and tell stories into their headsets as they played, including delving into personal and introspective conversation more than they ever had in person [7]. Some non-profit organizations hand-pick military personnel and veterans and pay for them to attend video game events while they are stateside, which helps to build a community around video gaming [7].

Video games not only provide veterans with a sense of comradery, but with a sense of purpose and validation of their military identity. A systematic review by Primack et al. [2] revealed video gaming improved psychological therapy outcomes, physical therapy outcomes, health education outcomes, pain distraction outcomes, and disease selfmanagement outcomes among other useful and positive health benefits in various age groups and populations. Clinical rehabilitation specialists are encouraged to discuss the use of video games to support recovery [10].

It is possible that gaming can serve as an adjunct to exposure therapy [11]. Benefits of video gaming can contribute to the development of leadership skills, building teams and even give veterans an opportunity to become professional internet streamers. Furthermore, video gaming can provide a rewarding role of being productive in gaming-related professions for veterans with disabilities [10]. For those with disabilities, gaming provides the safe harbor of home and comradery behind the screen where physical disability limitations no longer matter and the gamer can project images and action of themselves that they dream of. This kind of interaction may improve self-esteem and serve as a real therapeutic mechanism and/ or adjunct to therapy.

PTSD, mTBI, Risk Taking and Substance Use Disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) are common in veterans with incidence rates between 13-17% and 12-16%, respectively [12]. PTSD and mTBI have has been linked to impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors. Veterans with PTSD who have high levels of disinhibition have a tendency to be aggressive, impulsive, and turn to the substance abuse. Substance use disorders in veterans are highly associated with post deployment risk-taking behaviors, such as interpersonal violence, aggressive driving behaviors, and suicide or homicide-related tendencies [13]. Moreover, PTSD is linked to poor physical health, homelessness, a decline in social well-being, aggression, and legal problems [14]. Veterans with substance use disorders and PTSD may demonstrate high impulsivity and additional challenges in securing and sustaining employment and personal relationships, which exacerbate symptoms and prevent recovery [15].

“Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy has the best empirical evidence of its therapeutic efficacy” [16,17]. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps veterans who suffer from PTSD and substance usage disorders to correct negative explanations through positive thoughts restructuring. Video gaming may be utilized in conjunction with CBT for veterans to replicate positive thinking of real-life experiences.

Veterans with risk taking behaviors and substance use disorders may benefit from various treatment modalities. Veterans’ satisfaction with treatment is associated with better treatment outcomes. Studies demonstrated that patients who receive more support in treatment and a variety of treatment options and services produce greater patient compliance with treatment and more favorable, improved outcomes [9,18]. Veterans are more likely to turn to the programs in which there is an absence of value judgments and stigma. Veterans, like many substance users or addicts, deny their problem and/or tend to resist treatments. For veterans, difficulty with authority figures may increase their resistance to treatment efforts such as formal classes or a psychoeducational approach about the danger of substance abuse and risk taking behaviors [9]. Plach and Sells [19] studied the challenges faced in a group of young veterans (aged 20-29) returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. When focusing on leisure occupations the young veterans identified socializing and participating in relationships as a significant challenge.

Anxiety and mood instability is known to negatively impact completion of residential treatment for substance abuse [9]. Inclusion of hobbies in a treatment program, specifically music/art or horticulture, allowed therapists to engage patients in discussions of how impulsivity, risk-taking, lack of concern for self or others, related to their performance in hobbies, which were meant to be pleasurable and were allowed in the program either individually or in teams [9]. Extrapolating from this work, focusing on hobbies and socialization through gaming, may help veterans to internalize the benefits of games as an analogy of pleasurable topics and interests and more adaptive social behaviors. Video gaming, utilized therapeutically, may allow veterans to feel free to examine past impulsive behaviors without feeling stigmatization or judgment. Therapists may consider engaging veterans in games while discussing substance use issues to connect pleasurable activities with the recovery process, rather than aversion or punishment [9]. Turning to hobbies in practice might enhance veterans’ motivation to change, help them to focus on the hobby as a pleasurable activity and pursue spending their time and energy there rather than on detrimental substances/substance abuse, and improve compliance with treatment, therefore, producing a more desirable safe and positive outcome [9].

Replication of Positive Thinking

Use of video gaming can replicate positive thinking of real life experiences. Video gaming contains a variety of resources that encourage social interaction among other players connected through online. This type of gaming produces social rewards, social meaning, and personal growth [20,21]. Video games can enhance information literacy by improving reading skills because of reading text embedded in video games. Persistence of finding the solution while playing video games can facilitate problem solving experiences in the real life situations [22]. Moreover, players can learn knowledge and skills from video games and connect these skills with the real positive life experiences in the real world outside of video game. For example, playing sport video games allows participants to learn and practice good sports moves and copy them during the real practice. Some Nintendo video games teach players about farm animal care - how to feed, wash and look after the horses. Video games players who are interested in the specific knowledge, like cars and mechanics, can learn about types of vehicles, car engines, and car historical components [22]. Video gamers can feel motivated to play video games, experience enjoyment, creativity, and have opportunity to control their lives by producing a positive meaningful activity [21].

Video Gaming and Relationships

Video gaming may become disruptive in relationships where the military personnel and/or veteran’s significant other deems video gaming as a threat or detriment to the relationship. Gaming may become pre-occupying resulting in distance and disconnect from loved ones. Gaming may dominate and consume time at the expense of lost engagement with loved ones. The non-gaming partner in a military and/or veteran relationship should ask themselves whether the veteran that is gaming is excessive and/or detrimental to the relationship or if the veteran is using this activity as a therapeutic tool. Does gaming provide an adaptive, healthy response that promotes well-being and an intermittent escape from painful realities? Does gaming serve as a preventative activity; engaging in health promoting behaviors vs. potentially dangerous or self-harming behaviors outside of the partner relationship? Is the video game distracting the military personnel or veteran from pain, substance abuse, or risk taking behaviors they would otherwise be engaged in? Is the veteran able to self-regulate gaming time consumption or is the gaming excessive and disruptive to the relationship?

The therapeutic effect of engaging in a meaningful and purposeful activity, such as gaming, is a large part of active duty and veteran culture. It is socially acceptable, has benefits, and can be used in a variety of ways. However, this is a key area for nurse practitioner intervention. NPs may assist veterans and their loved ones to recognize potential negative impact of gaming, redirect excessive or detrimental gaming to therapeutic gaming, and support the veterans and families in repair of relationship damage with appropriate counseling and resources.

Conclusion

Video gaming provides military personnel and veterans a way to decompress, therapeutically relax, relieve stress, help them to disconnect from traumatic stress disorders, and decrease participation in risk taking behaviors including substance usage, as military and veterans garner potential positive health benefits. The literature suggests that video gaming presents an opportunity for military personnel and veterans to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

It will be important for researchers to continue to study and test the effects of video gaming on veterans to determine how to utilize video gaming to achieve positive outcomes. It will also be important for researchers to better understand veterans and their gaming practices.

The authors are currently investigating veteran video gaming behaviors, emotions, and opinions in an IRB approved online study and will publish results as soon as they become available in an effort to discover and uncover additional information and data on this topic.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. No disclosures applicable.

References

- NPD (2019) 2019 Year-End Expectations for the U.S. Video Game Market.

- Primack BA, Carroll MV, McNamara M, Klem ML, King B, et al. (2012) Role of video games in improving health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 42: 630-8.

- Bush NE, Fullerton N, Crumpton R, Metzger-Abamukong M, Fantelli E (2012) Soldier’s personal technologies on deployment and at home. Telemedicine and e-Health, 18: 253-263.

- Bush NE, Wheeler WM (2015) Personal technology use by U.S. military service members and veterans: An update. Telemed J E Health 21: 245-58.

- Wee H (2016) How video games are helping American veterans. CNBC

- Banks J, Cole JG (2016) Diversion drives and superlative soldiers: Gaming as coping practice among military personnel and veterans. Game Studies, 16

- StackUp (2015) Who We Are.

- Etter D, Kamen C, Etter K, Gore-Felton C (2017) Modern Warfare: Video Game Playing and Posttraumatic Symptoms in Veterans. J Trauma Stress 30: 182-185.

- Decker KP, Peglow SL, Samples CR (2014) Participation in a novel treatment component during residential substance use treatment is associated with improved outcome: A pilot study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 9: 7.

- Colder Carras MC, Kalbarczyk A, Wells K, Banks J, Kowert R, et al. (2018) Connection, meaning, and distraction: A qualitative study of video game play and mental health recovery in veterans treated for mental and/or behavioral health problems. Soc Sci Med 216: 124-132.

- Elliott L, Golub A, Price M, Bennett A (2015) More than just a game? Combat-themed gaming among recent veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Games Health J 4: 271-7.

- Combs HL, Berry DTR, Pape T, Babcock-Parziale J, Smith B, et al. (2015). The effects of mild traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and combined mild traumatic brain injury/post-traumatic stress disorder on returning veterans. J Neurotrauma 32: 956-66.

- James LM, Strom TQ, Leskela J (2014). Risk-taking behaviors and impulsivity among veterans with and without PTSD and mild TBI. Mil Med 179: 357- 363.

- Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, Tanielian T, Jaycox L (2015) Prevalence of risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17: 37.

- Heinz AJ, Makin-Byrd K, Blonigen DM, Reilly P, Timko C (2015) Aggressive behavior among military veterans in substance use disorder treatment: The roles of posttraumatic stress and impulsivity. J Subst Abuse Treat 50: 59-66.

- Hollon SD, Stewart MO, Strunk D (2006) Enduring effects for cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Annu Rev Psycho 57: 285-315.

- Solomon SD, Gerrity ET, Muff AM (1992) Efficacy of treatments for Posttraumatic stress disorder: An empirical review. JAMA 268, 633-638.

- Berkowitz B (2016) The patient experience and patient satisfaction: Measurement of a Complex Dynamic. Online J Issues Nurs 21: 1.

- Plach HL, Sells CH (2013) Occupational performance needs of young veterans. Am J Occup Ther 67: 73-81.

- Arbeau K, Thorpe C, Stinson M, Budlong B, Wolff J (2020) The meaning of the experience of being an online video game player. Comput Human Behav Rep 2: 100013.

- Shi J, Renwick R, Turner NE, Kirsh B (2019) Understanding the lives of problem gamers: The meaning, purpose, and influences of video gaming. Comput Human Behav 97: 291-303

- Gumulak S, Webber S (2011) Playing video games: Learning and information literacy. Aslib Proceedings 63: 241-255.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi