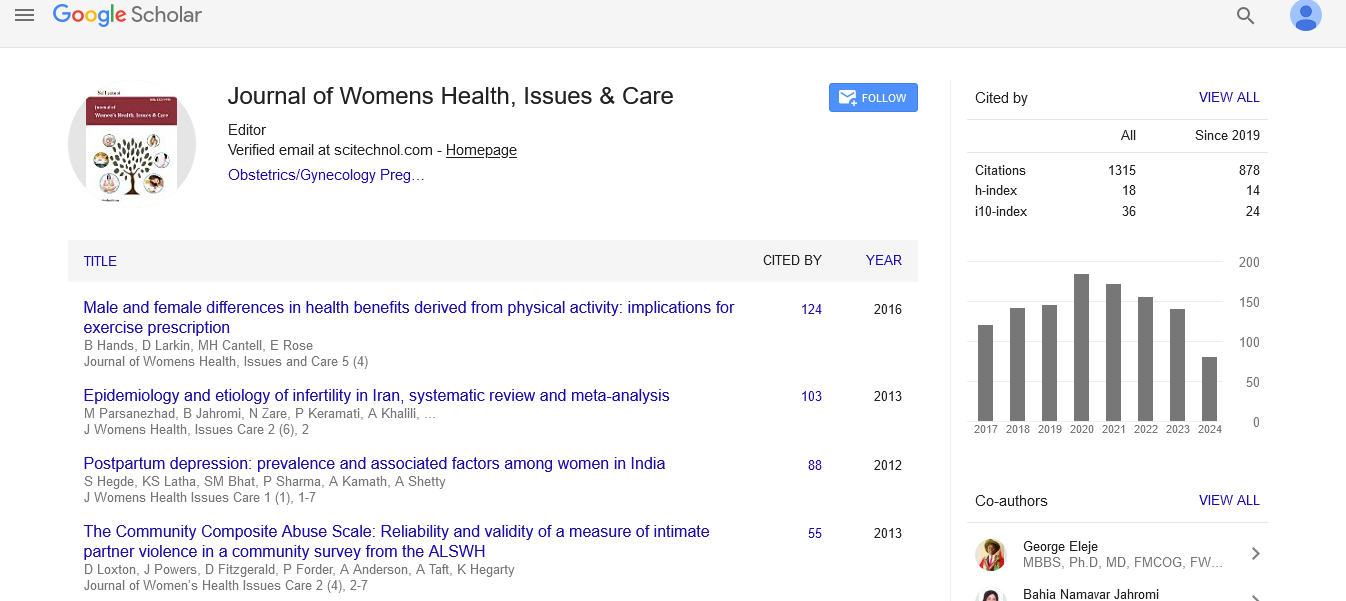

Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 3 Issue: 1

Breast Cancer Survivorship Optimizing Follow-up Care: Patients Perspectives of their Practical Needs

| Savitri Singh-Carlson1* and Cindy Gotz2 | |

| 1School of Nursing, California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, CA, USA | |

| 2Memorial Care Todd Cancer Institute, Long Beach Memorial, Long Beach, CA, USA | |

| Corresponding author : Savitri W Singh-Carlson, Ph.D. RN, APHN, School of Nursing, California State University Long Beach, Long Beach, California, USA Tel: (562) 985 4476 E-mail: savitri.singh-carlson@csulb.edu |

|

| Received: September 11, 2013 Accepted: December 10, 2013 Published: December 16, 2013 | |

| Citation: Savitri SC,Cindy G (2014) Breast Cancer Survivorship – Optimizing Follow-up Care: Patients’ Perspectives of their Practical Needs. J Womens Health, Issues Care 3:1. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000131 |

Abstract

Breast Cancer Survivorship – Optimizing Follow-up Care: Patients’ Perspectives of their Practical Needs

Breast cancer is still recognized as the most common cancer among American women with 1 in 8 women (12%) who will develop invasive breast cancer and about 39,510 women who will die from breast cancer, with 23,644 expected cases for California in 2013. Although breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women, exceeded only by lung cancer, death rates from breast cancer have rapidly declined since 1990, with larger decreases in women younger than fifty due to earlier detection, surveillance, increased awareness and improved treatment, resulting in more than 2.9 million breast cancer survivors (BCS) in the United States.

Keywords: Survivorship care plans; Breast cancer survivors; Physical and psychosocial impacts of breast cancer; Life stage

Keywords |

|

| Survivorship care plans; Breast cancer survivors; Physical and psychosocial impacts of breast cancer; Life stage | |

Introduction |

|

| Breast cancer is still recognized as the most common cancer among American women with 1 in 8 women (12%) who will develop invasive breast cancer and about 39,510 women who will die from breast cancer, with 23,644 expected cases for California in 2013 [1,2]. Although breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women, exceeded only by lung cancer, death rates from breast cancer have rapidly declined since 1990, with larger decreases in women younger than fifty due to earlier detection, surveillance, increased awareness and improved treatment, resulting in more than 2.9 million breast cancer survivors (BCS) in the United States [1-5]. Because of the growing recognition of cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of the cancer trajectory, development of efficient and effective strategies or care plans for the organized transitioning of patients, from active treatment at a specialized cancer centre to post-treatment care in the community, is now being seen as critical to the overall health and well-being of patients [6-8]. | |

| An overarching theme of American Cancer Society’s 2015 challenges is eliminating disparities in the cancer burden between different segments of the U.S. population [6]. Complex and interrelated disparities such as income, education, housing and standard of living; socioeconomic inequality and social barriers to cancer prevention and treatment services; culture and community surroundings account for gaps in health care and well-being within the multiethnic and underrepresented groups of California [1-9]. | |

| The Institute of Medicine’s report on cancer survivorship recommends that cancer patients completing treatment should be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up care plan that is clearly and effectively explained and that this care plan should be reviewed with the patient during a formal discharge consultation [7,8]. Although most health care providers recognize the value of an effective follow-up care plan [10-16], a limited number of centres implement survivorship programs that are patient-focused, and generally do not provide survivorship care plan (SCP) as a component of cancer care in California. | |

| Long-term survivors of breast cancer have persistent difficulties with fatigue; pain; sleep; psychological distress; fear of recurrence; family distress; and uncertainty over the future, and may face social concerns related to employment and finances [10-23]. Although results imply a universality of physical, psychosocial, and practical experiences that echo most BCSs needs; there are some reported variations among different age groups, especially life stages that correlate with human development changes [10,13,14,17]. However, younger age of BCSs has been reported to be connected with greater care needs after treatment [24,25]. This indicates that in order to support BCSs to deal with possible impending side effects of cancer treatments, importance should be placed on the significance of continuity of care and consistent communication between different health care providers at the time of transition, from completion of treatment to surveillance in order to help reduce feelings of anxiety and abandonment [10,11,15]. | |

| In addition to the impact upon patients and their families, survivorship issues and concerns for patients’ quality of life long term, can have a huge impact upon health care resources [4,7,18] especially when patients are not informed on timely screening and regular checkups post-treatment. Effective care following completion of active treatment, influences effective health care utilization by patients [4,8,25]. More intensive psychosocial care in the form of group therapy after completion of breast cancer treatment has been shown to decrease health care billings on the order of 23.5% compared to patients who receive usual care [4,8,10,13,14,22,26]. These results can be heightened by the diversity within our population in the United States, especially since a breast cancer diagnosis is not unique to any race or age. Given the evidence presented here of longterm physical and psychological impact of breast cancer treatment and BCSs quality of life, post-treatment, along with barriers such as resources and health care system structuring in the development and implementation of SCPs, it was important to pursue this study. | |

| The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore experiences and concerns of BCSs in order to determine the impact of curative treatment, post-treatment and to better identify their preferences for the content of the SCP. Furthermore, we examined how differing age groups, health care system structuring, and social influences may impact BCS experiences post-treatment as they transition from active treatment to survivorship. | |

Materials and Methods |

|

| A descriptive study design utilizing a qualitative approach was a fit for this study in order to explore impacts of breast cancer treatment experienced by survivors and to identify preferred content and format of SCP. This choice of inquiry lent itself to collect rich, detailed data that provided insight by describing how these BCSs experiences may differ from the majority of BCS needs, post-treatment [27,28]. This study was conducted at a community cancer centre which has provided peer support and traditional support programs delivering psychosocial support for BCSs for more than 14 years old. | |

| Informants | |

| At the time of the study, there were seventy-three BCSs on the support services list-serve. All BCS on the list-serve were invited to participate, via email addresses provided by the program administrator. An introduction letter describing the study, potential time and location of the interviews was emailed to BCSs. Those who responded to the email invitation were screened for inclusion criteria by the researcher and further information about the study was provided to them via email after they expressed an interest to participate. To improve response rates, a second email invitation was sent to non-responders two-three weeks later. A total of sixteen participants agreed to participate. Although we had hoped for a larger response rate, we realized that some women may have changed their email address or were not using this form of communication at this time. | |

| Data collection | |

| Ethical approval was received from The California State University, Long Beach and hospital institutional review boards. After providing written consent, participants were invited to be part of focus group interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Semi-structured interviews and field notes consistent with qualitative methodology were utilized to collect and analyse data [27-29]. Two, 1-2 hour focus group interviews were conducted in a private setting at the community resource centre in a social meeting setting with six face-to-face 35-45 minute interviews at a place that was convenient for them. Both interview methods followed the same format with focus group participants being initially informed of the rules for conducting this style of interviews. All interviews were conducted by the same researcher (first author – SSC) and facilitator to ensure consistency [27]. Use of thoughtfully prepared semi-structured questions and attentively listening to participants’ responses, intuitively, along with careful critiquing of each incoming interview ensured quality data that was rich and detailed [27,28]. These questions were used as a guide in order to ensure all informants were asked the same questions in more or less the same order to allow rich data: “1. Could you please share with me the impacts of the breast cancer treatment on your life?, 2. After the completion of your cancer treatment, if a care plan was given to you upon discharge to help you take care of yourself, what information should be included in it?” These initial questions were followed by direct questions posed to help elaborate on women’s experiences in order to determine whether these BCS’s experiences differed from other BCS in other settings. The number of participants was deemed appropriate when similar themes began emerging from the data, and similar stories were being heard. | |

| Data analysis | |

| As recruitment, data collection and analysis continued, a recurring pattern was revealed due to the participants’ age variation and their experiences, whereby it seemed important to stratify age in order to provide an even distribution of women’s age groups and to note any variation due to age factor for this group. Therefore, participants were stratified into different age groups: 35-44, 45-54, 55-64 and >65 since this stratification is comparable to life developmental stages. This stratification also provided meaningful life stages stratification as it corresponded to peri-menopausal and post-menopausal groups; and to those women who were of childbearing age or raising children (<44), those who were still employed (45-54), those considering retirement (55-64), or retired (>65). This decision proved to be logical since it provided rich meaningful data that represented BCSs experiences of the impacts of cancer treatment and their preferences for the contents of the survivorship care plan, which seemed to be dependent on their life stage. However, since only one participant was recruited for >65, it was impossible to provide meaning for this group, so this participant’s data was analyzed with the 55-64 year age group. Transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis to explore the short and long-term effects of breast cancer treatment, and content analysis, to identify content of the SCPs by age group (life stage). | |

| Thematic analysis helped to further identify common threads and patterns in these women’s experiences of breast cancer post-treatment [30]. Audio-recorded interviews and field notes were first checked line-by-line for accuracy before analysis began. Nvivo 8 software, a computer-assisted qualitative data management program, was used to code, store, and organize data. Research team members and coauthors met to read the two initial interviews and to discuss emerging categories and formulate coding framework. Analysis was done simultaneously with data collection by coding for similar categories along with constantly comparing data, in order to identify recurring categories, emerging themes and patterns [30,31]. This focused coding process helped to integrate data and to further describe larger segments of rich data that reflected emerging themes. | |

Results |

|

| Participants | |

| Sixteen participants ranging from 35 to 69 years old of age, with a mean of 52.5 and a median of 50 participated in the study. Five women (31.25%) were 35-44; five (31.25%) were 45 to 54; five (31.25%) were 55-64; and one (6.25%) was >65. Stratification at participant recruitment achieved an even distribution for 3 groups with only one participant for >65 age group; therefore this data was integrated into the data. All women were educated at either college or university level and had adequate medical insurance coverage. Table 1 presents the demographic information for the participants, which illustrates diversity. | |

| Table 1: Characteristics of participants. | |

| Thematic analysis | |

| The impacts of breast cancer were broad and varied by age group for the sixteen women in this study. Fatigue and fear of recurrence were the most intense and universal physical and psychosocial impacts of breast cancer treatment, experienced by women of all ages. However, the burden of a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment that centred on financial, social support issues and preference of SCPs identified “practical issues” as a universal theme among these women. Emotional and social effects were more intense in younger patients, with women in the middle age group experiencing more concerns centered on financial and social support issues. Important elements included: treatment summary, information on nutrition/exercise, expected side effects, signs/symptoms of recurrence, follow-up schedule, and updates on changes to recommended care. Preferred format for SCP is similar for all groups. Women preferred oncology nurses to provide the SCP at the beginning or at the end of the treatment and preferred written materials in lay language, telephone follow-up resource person and electronic bulletins for communicating updates. Table 2 presents themes and sub-themes of participants’ physical, psychosocial, and practical experiences. | |

| Table 2: Themes representing participants’ experiences. | |

| Physical impacts | |

| This theme of physical impact was generally described as being the most impressionable due to the debilitating nature of side effects of the cancer treatments such as fatigue coupled with cognitive issues and memory loss, loss of libido leading to sexuality issues, reproductive, hormonal and aging processes, and concerns around reconstruction surgery. This theme highlighted how BCSs generally adapted to learning new ways of doing practical tasks of activities of daily living, that changed from the original ways of doing things as they dealt with deficits, associated with physical impact of the cancer diagnosis and its treatment. Participants felt they had to set personal boundaries of how much they were capable of, which was also dependent on the natural process of aging limitations. Women had to set a new normal for activities they had been able to comfortably perform prior to the cancer diagnosis. This meant redefining lifestyle post-treatment in comparison to the pre-treatment, which also led to some despair and distress for some women; however most women took it in stride and knew they had to battle through the cancer diagnosis and treatment and change their way of life and their goals (<44 years old). | |

| Fatigue/reduced energy level: Most women identified with this theme as the being most impacting, especially while going through the treatment; however they were surprised when the energy level would wane even after a year post-treatment. Although these BCSs described feelings of disappointment at their fatigue level, they shared how they found different ways of accommodating this level of fatigue. As mentioned earlier, this led to setting new boundaries and goals and setting a new normal for their lives and accommodating to the limitations without dwelling on them. This is when most women felt they could conquer the cancer and find new ways of dealing with the tasks ahead of them and adapting by taking breaks during the day (45- 54 years old). Women from all ages shared similar levels of fatigue; however it seems that aging process placed some subtle limitations women’s current activity levels. Verbatim excerpts are presented in Table 3. | |

| Table 3: Verbatim excerpts. | |

| Cognitive level changes: Decreased levels of memory and ability to concentrate was very heartbreaking for women of all ages, but what made it worse for them was that at times of need they experienced difficulty organizing their thoughts. Cognitive level changes such as decreased memory, decreased ability to concentrate and loss of quick responses to questions were identified. Impairment with word retrieval made it even harder for them, especially when they were caught off guard when they forgot important points within conversations. Younger women, especially those <44 and 45-54 year old groups seemed to have a higher impact of memory loss and struggled with remembering details. Cognitive level changes were seen as distracting and an interruption in life process; since a person’s cognitive level should normally change due to the aging process. | |

| Menopause/loss of libido/and sexuality issues: Women who were on hormonal therapy seemed to be most impacted by irregular menstruation or loss of it coupled with hot flushes, which was difficult for those who were of menopausal age, since they did not know if this was true menopause or it was tied to the treatment. Loss of libido was a concern for women, especially those who were married, because they did not have the desire to be sexually active with their spouses, leading them to feel ashamed, or feeling like they had let their husbands down. Some women felt personal losses to their sexuality as partners in their marriage when they could not be as intimate as they used to be prior to the cancer diagnosis, surgery, the and the treatment. This loss of libido, accompanied by the natural process of menopause left them feeling alone within their relationship, especially when they “felt their bodies had let them down”. However, participants were generally pleasantly surprised as women experienced supportive relationships, leading them to feel confident within their marriage “My husband was the greatest help and support during treatment because caregivers they’ve also gone through a big thing and things are changing for them” (<44 years old). | |

| Reconstruction surgery: Most women felt that reconstruction surgery was an option, but were still afraid of taking the option of surgery, especially due to fear based on the rate of recurrence. Making decisions regarding opting for reconstruction at the time of surgery or post-treatment was difficult as they were uncertain of the future. This theme was experienced by women of all ages; however it was felt deeper by those of 45-54 year age group who felt they wanted some normalcy to their appearance and opted for reconstruction surgery earlier rather than later. For some women, this concept was tied into their sexuality and of being a normal woman. | |

| Weight gain/diet: Participants’ were concerned when they could not stay at their average normal weight they had been in the past, especially after completing treatment. This was complicated due to their perceptions of wanting to eat the right type of food to stay healthy and keeping their immune system boosted, but ensuring they did not over eat which would lead to weight gain. This was a constant battle for some women who had generally struggled with keeping at a healthy weight all their lives, but now felt it heightened because they were forced into taking medications with a side effect of weight gain. | |

| Psychosocial impacts | |

| The theme of psychosocial impacts had various facets of emotional strength which were identified as feelings of comfort and support from loved ones and from peer support that were paired with them from the peer mentor program. Fear of recurrence, uncertainty, and fear of the unknown were identified as major psychosocial concerns by most participants. Other psychosocial impacts were a result of reduced activity, cognitive and energy level limitations experienced, due to the physical impact of treatment. Feelings of despair due to these limitations led to bouts of depression that affected their quality of life. | |

| Most women felt insurmountable family, social and emotional support from their partners and friends. They shared the negative as well as positive impact of going through the cancer diagnosis and treatment. Most of the themes were universal with some unique age related impacts that will be presented here. | |

| Fear of recurrence/Uncertainty/Fear of unknown: Fear of recurrence was of paramount worry and prevailed for women of all ages, especially uncertainty and fear of the unknown of cancer disease and its unknown manifestations. Although this impact was universal, the degree of emotional intensity and components of fear of shortened life varied within the age groups, especially for those younger <54 years old of age, who had young families and felt cheated out of their plan they had envisioned for their lives. Most women felt the need to keep in close contact with oncologists in order to keep their mind at rest regarding recurrences. Interestingly, some women had not communicated the cancer diagnosis and treatment to their family physicians, because they felt family physicians would not be able to detect any recurrence, whereas the oncologist would. | |

| Body image/sexuality/identity: Body image was tied into one of multiple losses for physical appearance of the body, women’s’ sexuality and sensuality tied to self-esteem, and their personal identity as a woman which was in turn tied to their gender and worldview as individuals within society. Changes to one’s appearance due to the surgical procedure and the cancer treatment was more of an image that was held within the mind since I can get reconstruction surgery and be the same or better than before, however I know inside that my body let me down. This theme was accepted by most women as they slowly worked through the process of loss and accepting the changes within their bodies. | |

| Experiences of support | |

| Participants’ of all age groups experienced diverse supportive relationships from family, partners, and friends who reacted to their cancer diagnosis with intense emotion that allowed for an easing of the mind, as they journeyed through the cancer diagnosis, into treatment and then into the survivorship role. They also shared those negative situations where people in their lives did not know what to say or said the wrong thing which did not leave them very hopeful. | |

| Spiritual awakening/inner strength/self-realization that social support and love changes outlook: Most women who had supportive relationships with their spouses were amazed at their feelings of feel good moments as I journeyed through the cancer treatment. I had a strong self-realization that I am very much loved and supported by my husband. This was amazing and allowed me to go through the treatment on wings (45-54 years old). Even participants who had family support from siblings or parents experienced love that changed their outlook on the meaning of social support. Some women expressed feelings of support and love that were spiritual in nature and it awakened thoughts of love and comfort knowing that I am cared for and loved in this way (<44 years old). | |

| Women who expressed these amazing feelings of social support and caring, leading to self-realizations and spiritual awakenings also shared an inner strength that afforded them to forge their way through the cancer treatment, regardless of how tedious it was to go for the month long treatment, day in and day out till it was finished (55-64 years old). Participants embraced these experiences and became self-advocates as they sensed feelings of self-worth and inner strength, while facing the normal fears of cancer and its treatment. However, this positive form of social support was not available for all participants who sought the traditional support services available or felt privileged they had peer mentor support that seemed unconditional. | |

| Peer support: The theme of peer mentor support was emphasised as being an integral part of the larger social system for women, regardless of whether they felt supported by their family and partners. Women of all ages who had connected with other cancer survivors had positive experiences whether in a formal or informal setting. Participants felt they could have accessed the traditional support service that is available through the various cancer organizations such as American Cancer Society or their own institutions; however it meant picking up the phone and asking for help and then explaining what my needs were and then having to go into the office. It is hard to do this while you are trying to gather your energy to survive some days (<44 years old). Peer mentor from the community who phoned them and shared their personal experiences that were similar and more meaningful provided me with hope that I could get through (45-54 years old). Knowing they had peer mentor support available at any time was an emotional and mental support for women. | |

| Practical issues | |

| Health care insurance – one more worry | |

| All participants in this study had ample health insurance coverage; however they were all saddled with having to sift through appropriate paper work that needed to be dealt with in a timely manner in order to avoid surcharges and letters stating that medical bills were not paid. This experience seemed to be an added burden that participants did not expect or need at this emotional time when they were already dealing with the cancer diagnosis, fatigue and reduced cognitive levels from the treatment side effects. Participants felt that information regarding this practical part of medical care would have been beneficial at the beginning. | |

| Being a survivor | |

| The meaning of being a survivor had some positive and negative connotations as women did not feel they had survived anything, but had just gone through being diagnosed with breast cancer and had received treatment for it (<44 years old); however others related to being identified as breast cancer survivors because it was a traumatic experience, the cancer treatment and living with the side effects, it is hard, yes I am a survivor (45-54 years old). Others expressed they were not in a car accident, ship wreck, or a plane crash, because living through something like this would mean that I survived something, not being diagnosed with cancer. This is just part of life (55-64 years old) However, interestingly the language used to describe the experiences of journeying through cancer and being a survivor were expressive as some participants shared that I am going to battle through cancer; I am going to fight this cancer and get over it; I decided right away that I was not letting this cancer take over, I was going to battle it; and I have friends who told me that I can get over this cancer. However others who did not recognise themselves as survivors felt that the word has been over used, I don’t even use it actually. I don’t even want to be called one. I mean, not that it isn’t true, but I just think it’s just being overused. So I just identify with what they said about you. I know I’ve had it, this sort of thing that I’ve overcome and I am done. Participants shared there were conundrums to being a survivor, especially after diagnosis when one did have to get over the emotional and physical impacts of treatments. | |

| Contents of the survivorship care plan and its practicality in accessing health care | |

| Content analysis utilised in this study identified participants’ of all ages agreeing that the survivorship care plan (SCP) had many practical benefits that would reduce a lot of unnecessary burden that is placed on the patient to remember the type of diagnosis, treatments and short/long-term side effects. A written SCP in a booklet format that BCSs could keep would be of benefit, if they ever moved to another state and needed their medical records or had a medically related diagnosis they were not aware of. Email updates were acceptable for future resources and updates. | |

| Relationship with interdisciplinary team – family physician/ oncology: Participants also felt a the practicality of a SCP in being able to keep it as a record of their treatment that they could take to other health care providers such as their family physicians, cardiologists, internists, dieticians, and therapists was practical. Most participants did not have a continuing health care relationship with their family physician, due to the type of health care insurance they had where they could access specialists on their own without family physician referrals. Others had never visited the family physician during their treatment to inform them of their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Women felt that a SCP would force an interdisciplinary team relationship between the family physician and the oncologist, especially post-treatment as we visit the family physician for other noncancer related health concerns (45-54 years old). Participants felt that collaborative teamwork is necessary as they move forward in their posttreatment cancer journey, especially in light of recurrence (55-64 years old); therefore the practice of preparing a SCP for the patient forces the oncologist to prepare one for the patient’s other team members (<44 years old). Table 4 presents contents and format of a survivorship care plan preferred by survivors. | |

| Table 4: Treatment summary/follow-up care plan. | |

| Resources and information: Participants felt that resources and information on where to access supportive care, types of exercise, diet/nutrition, reconstructive surgery, recent information on side effects, prevention and screening, along with a scheduled follow-care plan for future blood tests, mammograms, regular physical checkups should form part of the SCP. Women of all ages expressed that the oncology nurse or a health care provider trained in oncology should be delivering the SCP at the end of treatments at a face-toface meeting with BCS; however most felt that communication about the extent of fatigue, cognitive level decrease and weight gain among others are details that could be provided from the beginning. | |

Discussion |

|

| Themes identified in this qualitative study mirror those of previous studies [10,13,14,18,22,23] about physical, psychosocial and practical impact of breast cancer treatments, and BCS preferences of the content of SCP; however the present study highlights the importance SCP and of including interdisciplinary healthcare team when transitioning the cancer patient post-treatment, which directs a scrutiny of the present health care structuring for cancer care. American Society of Clinical Oncology reports managing cancer care in the United States health care system is extremely complex, especially since over three-quarters of oncology care happens in multiple outpatient settings [19]. This complexity is further heightened when many cancer patients during treatment are managed by multiple oncology specialists and are not generally under supervision from their primary care physicians [4,8,1-18,30,31] unlike their Canadian counterparts. At the British Columbia Cancer Centre, where breast cancer patients having finished active treatment are usually discharged with a letter from the provincial cancer centre containing the patient’s discharge summary to the care of their primary care physician within a year [10,13-15]. | |

| American Cancer Society, IOM, and Livestrong Foundation [6,7,32] all highly recommend that SCP be an important component of cancer care; however many survivors do not receive a SCP or if they do, then critical elements may be missing [33]. Generally, oncologists may be focused on treating the disease rather than the survivor’s post-treatment needs, resulting in slow implementation of treatment summaries and SCPs as standard practice [15-18]. SCPs are a hot topic at most cancer care meetings, especially in light of the Commission on Cancer’s new standards released last year that require all American College of Surgeons accredited facilities provide SCPs to all patients by 2015 [34]. This 3 year phase in period will better understand barriers to the development and implementation of SCPs. | |

| The notion of bridging multiple divides between the interdisciplinary health care team is seen as an important beginning discussion point, especially between the oncologist’s clinics to the primary care physician’s office [33]. Other studies confirm the importance of SCP and report how this will enhance quality of life and reduce anxiety and increase communication between health care providers which leads to patient-centred care [23,30,35,36]. Reports from IOM and other studies confirm our findings that coordination between specialists and primary care providers ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met [7-16]. However, Klabunde et al. report that over 70% of oncologists fulfill the primary care role by providing follow-up care themselves instead of utilizing a shared model of comanaging with a primary care provider [31]. Furthermore, 27% of oncologists stated they did not routinely communicate with their patients’ about who should be responsible for post-treatment care [31] and identified the development of SCP time consuming and an uncompensated burden. | |

| As reported in this study, SCP plan helps survivors expect what is coming next by providing some predictability and order to their follow-up care [37] that allows them to self-manage their care following treatments. Current literature coins the term “re-entry phase” to describe that return to “normal” life at the end of active treatment which seems to fit this population [23,38]. Stanton and others speak to this phase and the importance of a SCP, especially in light of loss of the “medical safety net” that occurs at the end of active treatment and results in needed education and addressing psychosocial concerns by the oncology team [23,33,38]. Roughly three quarters of American Society of Clinical Oncology members surveyed in 2004, share they should be involved in patients’ ongoing care of general health maintenance, screening, and prevention, however only 60% felt comfortable providing them [37]. In light of the increasing population of BCS and access to long-term care treatment by oncologists, collaborative models into primary care and self-management approaches will be warranted [3,11,12,23]. | |

| Our study has limitations in the number of participants; however because of the qualitative nature of this study, findings provide meaningful narratives that illustrate depth to existing knowledge. The population was recruited from the peer community support group which may bias the findings; however it also further reinforces the need for peer-mentoring for BCS. Identifying the content of and format of SCP before the planning and development stage of SCPs is strength in this study as it is patient-centred in its identification of the population’s need. More diversity among the population related to ethnicity, education, medical insurance coverage or socio-economic status would have provided breadth to the study. | |

| Recommendations for cancer care providers | |

| Recommendations include collaborative care programs that involve recognition of psychosocial problems and patient education from the beginning of diagnosis by utilizing the self-management model where patients have a key role of advocating for themselves, by taking an active role in their education. Future research on a more diverse population who are socio-economically disadvantaged and have minimum to no health care insurance coverage is needed, in order to identify and address other BCSs populations’ needs. In light of Grunfeld et al. [39] study reporting that receiving a SCP did not really make a difference for cancer survivors, contextual information about the setting and the population is important when exploring the efficacy or feasibility of survivorship care planning [3]. Evaluating needs of the community of cancer survivors and the health care providers’ readiness along with health care structuring of institutions, would be vital as we prepare to address the Commission on Cancer’s new standard, requiring all American College of Surgeons accredited facilities provide SCPs to all patients by 2015. Participants’ voices stating the need for interdisciplinary care team approach, evidenced in the literature, should be attended to, in order to reduce health care costs, enhance patients’ self-management roles, and to enhance quality of life for the increasing number of breast cancer survivors. | |

Acknowledgments |

|

| Authors acknowledge California State University, Long Beach for funding this project as an internal grant and to the participants who gave their time willingly and wanted to share their stories and the student research assistants. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi