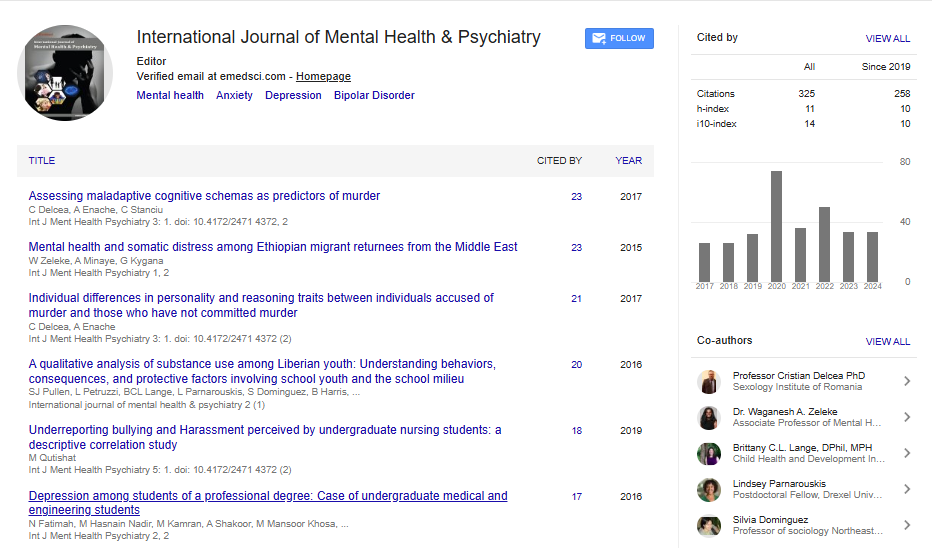

Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 2 Issue: 1

A Qualitative Analysis of Substance Use among Liberian Youth: Understanding Behaviors, Consequences, and Protective Factors Involving School Youth and the School Milieu

| Samuel J Pullen1, Liana Petruzzi2,3, Brittany CL Lange2,4, Lindsey Parnarouskis2, Silvia Dominguez2,5, Benjamin Harris6, Nicole Quiterio7, Michelle P Durham8, Gondah Lekpeh6, Burgess Manobah6, Siede P Slopadoe9, Veronique C Diandy9, Arthur J Payne9, David C Henderson2,5,8 and Christina PC Borba2,5* |

| 1St. Luke’s Healthcare System Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Boise, ID, USA |

| 2Division of Global Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, , USA |

| 3University of Texas at Austin School of Social Work, Austin, TX, , USA |

| 4Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA |

| 5Harvard Medical School, Boston MA, USA |

| 6AM Dogliotti College of Medicine, University of Liberia, Monrovia, Liberia |

| 7Bay Area Children's Association, Oakland, CA, USA |

| 8Boston University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA |

| 9Christ Jubilee International Ministries, Lowell, MA, USA |

| Corresponding author : Christina Borba PHD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Director of Research, the Chester M. Pierce, MD Division of Global Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, 25 Staniford Street, 2nd Floor, Boston, MA 02114, USA Tel: 617-512-9089 Fax. 617-723-3919 E-mail: cborba@mgh.harvard.edu |

| Received: December 05, 2015 Accepted: February 15, 2016 Published: February 19, 2016 |

| Citation: Pullen DO SJ, Petruzzi L, Lange BCL, Parnarouskis L, Dominguez S, et al. (2016) A Qualitative Analysis of Substance Use among Liberian Youth: Understanding Behaviors, Consequences, and Protective Factors Involving School Youth and the School Milieu. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 2:1. doi:10.4172/2471-4372.1000116 |

Abstract

Objective: Substance use is a significant and common problem among school-aged youths throughout Africa. Like other countries on this continent, the West-African nation of Liberia is recovering from civil war. A well-educated population of young people is critical to the recovery efforts and long-term success of Liberia. Substance use by school-aged youths has important public health consequences that could undermine Liberia’s post-conflict recovery efforts. We wanted to better understand the culturally significant themes and subthemes related to substance use among youths attending public schools in Monrovia, Liberia.

Methods: A qualitative research design was used to collect data from 72 students attending public school in Monrovia, Liberia. Nine focus groups of 6-8 students from three public schools were facilitated using a semi-structured format to guide discussions on substance use. Student narratives were translated and re-occurring themes and subthemes were coded and analyzed.

Results: Four emergent themes described in this study were:

- Behaviors associated with substance use

- Consequences associated with individual use

- Consequences of substance use that affected the school milieu

- School-related factors that were protective from substance use.

Subthemes associated with substance use included concealment of substances, intoxication and disruption of the classroom environment, expulsion from school, school drop-out, and school as protective against substance use.

Conclusion: Liberian school-aged youths described important themes and subthemes associated with substance use occurring within the school milieu. These data have germane public health ramifications, and could help inform larger epidemiologic study methods and public health interventions for Liberia and countries with similar profiles.

Keywords: Post-conflict Liberia; Focus groups; Children and adolescents; Substance use; School

Keywords |

|

| Post-conflict Liberia; Focus groups; Children and adolescents; Substance use; School | |

Introduction |

|

| In 2003, the West-African nation of Liberia emerged from fourteen years of civil war, which ravaged the country’s economic, health, and education infrastructures [1]. Chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and substance use disorders continue to plague Liberia’s population, and hinder recovery efforts [1,2]. Economically, Liberia remains one of the poorest countries in the world. One strategy to reverse this statistic would be to improve the education, and high unemployment rate of Liberia’s population, the majority of which are youths (comprising approximately 65% of Liberia’s population of 4.1 million persons) [3,4]. Such an intervention was cited by Liberia’s president as being critical to improving the country’s future peace and security, and preventing the country from lapsing back into civil war [4]. | |

| Youths in sub-Saharan African countries, such as Liberia, share an important bidirectional relationship with the socio-economic forces that impact post-conflict societies; including changes in political institutions, rapidly expanding global networks and the increasing importance placed on school and higher education in workforce and economic development [5]. This underscores the importance of establishing stable school environments and actively engaged youths who are motivated to pursue higher education in post-conflict societies [5]. Although some progress has been made in improving education rates among youths in sub-Saharan Africa more concerning trends towards high-risk behaviors such as alcohol and other substance use are also on the rise [5]. | |

| Substance use among youths is a significant problem globally. Substance use is associated with increased risk for a number of well-established consequences including impaired peer relationships, mental illness, increased risk for suicide, high-risk sexual behavior, HIV/AIDS, disrupted learning, truancy, increased school drop-out rates, and poverty [6,7]. Substance use among school students in many African countries is also common and has been associated with similar consequences [8-11]. | |

| Given the importance of school, and higher education in sowing the seeds of post-conflict recovery; substance use among youths in sub- Saharan countries, such as Liberia, is a highly relevant public health problem, and could undermine progress made in these fragile countries emerging from conflict [8,9,12,13]. Furthermore, Liberia is one of several sub-Saharan countries that have become even more fragile in the aftermath of the recent Ebola outbreak, which has put significant strain on the government and healthcare system [14]. | |

| Alcohol and substance use is thought to be highly prevalent among secondary school students in Monrovia, Liberia. In one pilot study using a cross-sectional survey of 802 Liberian school students, 51% of respondents reported using alcohol, and 9% of respondents reported using marijuana underscoring how prevalent alcohol and substance use is among secondary school students in Monrovia, Liberia [12]. However, less is known about the specific behaviors, consequences, or cultural idioms associated with substance use among youths attending school in Liberia [12]. Thus, we sought to better understand important themes and subthemes associated with substance use among youths attending public schools in Monrovia, Liberia. | |

| Our research group used a qualitative research design to solicit information about substance use from public school students divided into small focus groups in Monrovia, Liberia. In this study we report on student responses specific to behaviors, consequences, and protective factors associated with substance use in the school setting. A better understanding of cultural idioms and themes from the student’s perspective could be helpful in laying the groundwork for larger epidemiologic studies, and help inform prevention strategies in Liberia and countries with similar profiles. | |

Methods |

|

| Study design | |

| A semi-structured, qualitative research design was used to collect information from nine focus groups with 6-8 students per group. A total of 72 public school students were recruited using a convenience sampling design. Each school had an all-female focus group, an allmale focus group and a mixed-sex focus group. Students were recruited and focus group discussions were conducted using a ‘best practices’ approach similar to what is discussed by Plummer-D’ Amato [15,16]. Specifically, we defined the term ‘focus group’ to mean a specialized group interview facilitated by a moderator to obtain data on participant attitudes, beliefs, vocabulary, and thought patterns from a relatively homogenous target population [15,16]. | |

| Group size adhered to the recommended number of 6-8 participants to optimize participant interaction [15]. The number of groups, nine in this case, adhered to the principal of saturation – the point where no new information was likely to be obtained by adding additional groups [15]. We attempted to reduce moderator bias by using a moderator who was not previously known to the participants, and was more likely to be emotionally detached from the subject matter in question. Additionally, moderators used a triangular method, a technique that helps assure reliability and credibility of qualitative research designs by seeking the same information using different interview techniques within the course of the same interview, to structure the format of interview questions [15]. As an example, in a semi-structured interview, an interviewer might begin by asking the focus group an open-ended question about substance use in the school setting, and later in the course of the same interview might ask more specific probing questions about themes of substance use in the school setting [15]. Alignment of responses to questions asked in different ways helped to assure their validity. | |

| Participants were recruited and enrolled in the study through the assistance of staff at these schools. Eligible participants could be male or female, were required to be enrolled in a public elementary, middle or high school in Monrovia, and were required to be able to provide written informed consent. | |

| Data collection | |

| Data was collected from focus groups on April 10, 2012 through April 12, 2012. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Liberia Institutional Review Board and the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. If a participant was under the age of 18, child assent was obtained along with parental/guardian consent. Participants were given copies of the consent form to bring home and discuss with their parent or guardian. Participants were explicitly given the right to refuse participation or to stop participation at any time. Participants were compensated with a $5 phone card for their time. Confidentiality was maintained through the use of study IDs for each participant and all identifying information was removed prior to transcription. Access to study data was restricted to the investigator and the research team. All electronic versions of the documents required password protection and storage on a secure network. | |

| All discussions were held using the preferred language of the students, and if they were non-English speaking, a Liberian medical school student translator was made available. An expert in qualitative interviewing and coding trained all study staff. Focus groups were recorded and notes were taken by both the primary interviewer and the Liberian medical school student translator during and after the focus groups to ensure accuracy. In the event of a mental health or medical crisis a local psychiatrist and medical provider was made available to contact. | |

| Study measures | |

| Students were initially asked open-ended questions inquiring about substance use. Interview questions were constructed using a literature search to inform the content and structure of the questions. The sole Liberian psychiatrist in the country was then asked to edit and adapt the questions to be relevant for study participants. Examples of questions included “I’m wondering if you know anyone or have met anyone that has used drugs such as alcohol or substances?” “Do parents have any influence on students smoking marijuana and drinking alcohol and coming to school?”Interviewers then used probing techniques in order to capture supplemental information regarding the participants’ responses to the research questions and to further engage students to share their personal experiences. For example, as a follow up to a description of a boy who brought food mixed with marijuana to school the interviewer asked, “So this is a boy that actually was in school. So what happened to him as a consequence?”Focus groups were run for approximately 90 minutes, and were facilitated by an interviewer - a research fellow from the parent institution, and a Liberian medical school student translator. | |

| Data analysis | |

| After the transcription of focus groups, which were completed verbatim, five coders who had undergone formal training in qualitative research, independently read the focus groups and met to discuss initial perceptions of the transcripts. To preserve the fidelity of the coding process, at least two members from our research group were required to code the transcription narratives. Upon independently coding the first three focus groups, coders met to discuss and agree upon codes to create a preliminary codebook, which was used as a template to identify similar themes when coding subsequent transcription narratives. After completion of the initial codebook, coders independently coded one focus group at a time, and then met for a period of time lasting 45 minutes up to two hours on a weekly basis, for a total of 25 meetings to discuss and agree upon codes, and add new codes to the codebook as necessary. If there were any disagreements among coders, they were managed by discussing the differing perspectives as a group, and arriving at a majority group consensus. If the coders could not come to a consensus at the time of discussion, the transcript excerpt in question would be recorded on a memo, and saved for future discussion after additional transcript narratives were coded to determine if there were recurring themes necessitating a new code be created, or how the transcript excerpt in question would best fit with already established codes. | |

| As coding proceeded, categories were clustered together, from broad topics such as “substance abuse,” to increasingly specific themes and subthemes, such as “alcohol use in a community setting”. A corresponding definition was also created for each code to ensure coding consistency. For each code added to the codebook, a consensus was reached between the coders to ensure inter-coder reliability. Thematic content analysis was conducted and data were coded based on reoccurring subject themes and patterns. NVivo software was used as a data management tool [17]. | |

Results |

|

| Descriptive data | |

| Students were divided into a total of nine focus group units, three focus groups from each school, comprising 6-8 students per group (Table 1). Data was collected from a total of 72 school students (37 male students and 35 female students), 24 students per school from a total of three public schools, ranging in age from 12-20 (Table 1). Reoccurring themes and subthemes associated with behaviors, consequences of substance use, and protective factors among schoolaged youths in public schools were identified in each of the focus group transcript narratives. We reported on specific subthemes related to each of the principle themes, and their relationship to substance use in the public school setting as discussed in the focus groups. | |

| Table 1: Demographics of Public School Student Participants in Focus Groups in Monrovia, Liberia. | |

| Analyzed interview data | |

| Important themes of substance use in the school setting were | |

| (i) Behaviors associated with substance use; (ii) consequences that affected or were related to the individual(s) using the substance; (iii) consequences that affected the school milieu sometimes used interchangeably with the term ‘school classroom environment’, which included other students, teachers, and the general environment of the classroom and school; (iv) Factors which students described as protective from substance use. | |

| A subtheme related to behaviors associated with substance use included concealment and bringing substances to school. Individually experienced consequences of substance use included subthemes of intoxication, misbehavior, confrontation with teachers or other authority figures, suspension, expulsion, and dropping out of school. Subthemes related to consequences affecting the school milieu included unknowingly ingesting a substance mixed with food or beverage, knowingly engaging in substance use which led to aggressive behaviors and caused disruption in the classroom, as well as interference with learning. Students also described aspects of school that they felt were protective. Students reported that school was a protective factor against substance use, early pregnancy, and was important for their future. | |

| As described in the focus groups, the four themes of behaviors, individual consequences associated with substance use, school classroom environmental consequences associated with substance use, and protective factors of school were important in providing context for a working model of how these themes of substance use among school-aged youths were interrelated (Figure 1). | |

| Figure 1: A proposed model of how important themes associated with alcohol and substance use in public school are interrelated as discussed in focus group narratives at three public schools in Monrovia, Liberia. | |

| Behaviors associated with substance use | |

| Concealment and Bringing Substances to School: Behaviors associated with substance use affecting individuals at school seemed to begin with students bringing alcohol or substances to school by either concealing the substance in their school bags or hiding the alcohol or drugs in food and beverage items. | |

| “Opium, cocaine, drinking liquor going to school.” | |

| “Yes some of them they carried it in their bags like their school bags because of the time people don’t check in the bags.” | |

| Parents, a potential and important source of influence on this behavior, were described as being unaware that this practice was occurring. | |

| “The parents don’t know anything about it. Parents are usually gone to work.” | |

| Substances were commonly hidden in food items such as kanyan - a popular Liberian food made of gari, sugar, and peanuts or beverage items such as juice, tea – called “direct”, or ‘Kool Aid’ sometimes identified by the cultural idiom “big mama”. | |

| “Sometimes they mixed those grass (marijuana) with a food that we eat called kanyan.” | |

| “Last year I had a friend who used alcohol all the time, even in class. It was red and they called it big mama. They sat back and would drink the alcohol in class. It was a group of them.” | |

| Reasons for bringing substances to school varied. Alcohol and other substances were used as a means of coping with social anxiety and public speaking,and were also viewed as aiding one in becoming more ‘active’ and socially outgoing. | |

| “According to him he is shy, so the only way that he can talk is unless he drinks alcohol.” | |

| “Sometimes they just want to be active among their friends.” | |

| Some students believed that using alcohol and substances before school would make them smarter. | |

| “According to him he said that when he takes alcohol and he comes to school he canbe smart, but he stopped it.” | |

| Still others used drugs and alcohol as a means of self-treating mental illness such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder if they had previously been forced to serve as a “child solider”in past conflict as an example. | |

| “Some people smoke and drink liquor to forget their problems. They’re frustrated so they do it to keep from committing suicide.” | |

| Students also described youths intentionally becoming intoxicated, identified by the cultural term “weesie” (which referred to ‘getting high’) prior to coming to school so that they could be disruptive in class. | |

| “As for me, I think its marijuana, most of our friends take in for selfdesire to disturb.” | |

| Individual consequences of substance use | |

| Intoxication and misbehavior: Intoxication and associated misbehavior were two important subthemes that emerged from the data that affected individual students. Students who brought alcohol and/or other substances to school were described as exhibiting varying degrees of intoxication in the classroom setting or other school functions such as a school “gala” similar to a school assembly. | |

| “Sometimes people come to school with liquor and drink on campus on gala day.” | |

| Intoxication from substance use was associated with altered mental states, physical effects, and repeated substance use was associated with increased risk for addiction. Students also described their intoxicated peer as struggling with their own learning, whether or not that individual experienced other ‘disrupted learning’ consequences related to substance use such as being suspended or expelled from school. Nearly all of the focus groups associated intoxication with misbehavior. | |

| “Because when you smoke and a teacher is teaching you don’t learn anything.” | |

| Students described various physical consequences of recurrent substance use, and altered mental states of intoxicated classmates. | |

| “It can damage your heart that it makes your intestine to damage like that. It can make your intestine rotten because every day you are out smoking on your lungs it can damage your lungs.” | |

| “It (opium) makes you behave like someone who’s crazy, makes you stupid in the head…acting, yelling, and misbehaving.” | |

| Students also described repeated intoxication as leading to longerterm deleterious physical and mental effects that also affected learning among individuals using alcohol and drugs regularly. | |

| “And mainly if you continue drinking alcohol it makes your mind weak and you cannot study anymore, and you will sleep all day, disturb the class, act rude so it really affects the mind.” | |

| Intoxication was also associated with misbehavior and subsequent disruption of the classroom environment. | |

| “On such occasions they agree to get drunk. They drink and then come to class, disturb the class and talk back at the teacher.” | |

| The link between substance use, intoxication, and misbehavior was described in nearly all of the focus groups. | |

| In some cases, it seemed clear that some students intended to misbehave in the classroom and intoxication from substance use accentuated this behavior. In other cases, it was unclear whether substance use was used as a rationalization for misbehavior and perhaps to escape consequences, or if students used substances with the intention of acting out in the classroom. Some student narratives clearly described a sense of bravado when interacting with the teacher (‘give talk to the teacher’) or other authority figure. | |

| “Some of them boast about it. They say they do drugs and get drunk before coming to school in order to be in ‘weesie’ (high) so that when the teacher talks they can ‘give talk to the teacher’.” | |

| Misbehavior seemed to be directly associated with confrontations with the teacher, which led to additional individual consequences such as being suspended or expelled from school. | |

| Confrontation with the teachers and expulsion from school: In many instances behavioral acting out seemed directed specifically toward the teacher. | |

| “When the teacher tries to stop them, they will go and fight the teacher. The last time a teacher entered in class and a boy took the opium and drank the liquor. So when the instructor enters the class, he started misbehaving.” | |

| According to students from these focus groups, confrontation with teachers led to the individual consequence of suspension or expulsion from school. | |

| “In our class, there was a boy who was very rude. He said if he doesn’t smoke, he couldn’t control his behavior. Even the teachers couldn’t control his behavior. He was given NTR (never-to-return/ expulsion).” | |

| Students stated that many of their disruptive peers who were expelled from public school were simply transferred to different schools. If their parents were affluent, those individuals expelled from school would be transferred to “big” schools or private schools. | |

| “They give them extra assignments, suspend or expel them. Most of their parents have money so they can afford to pay money to go to another school.” | |

| Students described a more permissive culture in private school classroomswhere students more openly used substances and teachers could be bribed. Some students who continued to use substances chronically would go on to develop features of addiction using the cultural idiom,“it becomes a part of you”. | |

| “Most of them attend private schools. They come there and smoke and drink.” | |

| “Some students now, going to the big, big schools they go they smoke enough; sometimes teachers can see them, but they can give the teachers money, the teachers can’t talk it. So they can just leave them alone, and when it grows inside of you, it just is part of you. Even you finish high school it will just be part of you, you will not do anything for yourself." | |

| Other students who were expelled from school were described as “street people” who were of lower socioeconomic class, and were described as living out in the streets, the community, or near venues where one could acquire drugs, identified by the cultural term “ghetto”. | |

| “The first thing is that they are not will to learn because they are street people. They stay in the streets all night and in the morning they come to class to embarrass the rest that are will to learn.” | |

| Students of lower socioeconomic background who were suspended from school returned to class after a period of time, although there was no indication that suspension from school resulted in changing an individual’s behavior; whereas poorer students who were expelled from public school returned to their community, as their parents were not able to afford private schooling. | |

| “And then they can give them suspension two months and after one day, people will see back in the class.” | |

| Expulsion from school served to remove a disruptive individual from the classroom environment thus leading to a potentially positive outcome for other students in the classroom. However, data from these focus groups underscored apparent differences in socioeconomic status among students in public schools leading to differing outcomes for students who were expelled from school, and the perception that expulsion from school was not an effective deterrent to using substances. | |

| “Yes sometimes they can expel them or they make them to work like clean up the campus, scrub bathroom, cut grass, but that don’t stop them because they can still go on and doing the same things.”. | |

| Additionally, expulsion from school halted an individual’s education, particularly poorer students, limited opportunities to learn about other critical topics such as STD’s and safe sex practices, and increased the likelihood that school-aged youths would be more prone to engage in criminal behaviors such as stealing and sexual violence. School-aged youths who were no longer attending school were at increased risk for committing acts of violence connected with substance use including theft, and sexual violence, which was described in many of the focus groups. | |

| “They will be stealing just to go buy drug or just to buy alcohol.” | |

| “Sometimes when boys smoke, they take people’s children to their rooms and rape them. They end up infecting children with all kinds of sickness.” | |

| Dropping out of school: Substance use was also associated with dropping out of school. | |

| “Because many at times some of our friends their parent can pay their school fees but at the end of the day because of the smoking (marijuana), they will not end the year and they will drop from school.” | |

| The subtheme of dropping out of school was separated from being suspended or expelled from school as the latter consequence was not considered to bea direct choice of the students, but was more directly connected to the consequence of misbehavior in school related to intoxication/substance use, whereas dropping out of school seemed to be a choice of students or a consequence of previous choices made by a student (i.e. recurrent substance use leading to addiction, unplanned pregnancy, etc.). | |

| “Some of our friend will register and be schooling, but when they start or find themselves with such life they don’t think about school anymore.” | |

| Symptoms of addiction, such as tolerance and withdrawal, obsession with procurement of the substance of choice, and impaired judgment and decision-making seemed to be more associated with individuals who dropped out of school. | |

| “That’s every day, sometimes she drinks constantly, and she comes from school, sometimes she can’t go to school. I try to talk to her, but she can’t even listen to me. She is not in school anymore.” | |

| When compared with students who were expelled from school due to substance-related misbehavior. Some students did not drop out of school until after high school. | |

| “Some have graduated from high school and are in the University of Liberia, but they end up dropping out.” | |

| Although students did not always indicate the reason for dropping out of school in the transcript narratives, it did seem to be related to a conscious choice on the part of the individual. Like expulsion from school, dropping out of school could lead to the individual ramifications of prematurely halting one’s education, and mitigating the protective benefits of staying in school. | |

| Consequences of substance use – school milieu | |

| Ingesting an unknown substance: Another consequence associated with concealing alcohol and drugs and bringing them to school wasthat other students might unknowingly ingest a particular substance. | |

| “They are some people who make tea with opium. Sometimes they put it in food, like kanyan and you eat it without knowing it.” | |

| Students described, “Not being yourself ” if they were to consume foods or beverages tainted with a substance such as opium. Students indicated that they often learned to stay away from foods that were commonly used to mix substances in such as kanyan. Thus, concealing alcohol and substances and bringing them to school not only led to individual consequences associated with intentional intoxication, but also led to other students within the school milieu unintentionally ingesting substances as well. | |

| Unintentional ingestion of alcohol and substances was also associated with intoxication and subsequent ‘misbehavior’. | |

| “They bring the clear cane juice (undiluted alcoholic beverage brewed in Liberia), and put kool aid in it so people think its juice. They drink it and start misbehaving all over the place.” | |

| Students did not describe any additional consequences associated with unintentional ingestion of substances such as confrontations with the teacher, expulsion, or dropping out of school. As such, unintentional ingestion did not appear to follow the same consequence trajectory of individual students who were knowingly using substances. However both intentional and unintentional ingestion of alcohol and substances were described as leading to intoxication and misbehavior, both of which were described as important consequences leading to disruption of the school classroom environment. | |

| Disruption of the school classroom environment: Overall, students felt that substance use was problematic in the school classroom environment. | |

| “Actually this smoking business is very much affecting us especially in this school I must admit.” | |

| Misbehavior by students who were intoxicated led to important individual consequences as previously described, but was also felt to have a negative impact on the learning environment for the entire class, and thus was an important outcome of substance use that affected other students proximate to the misbehaving individual. | |

| “I feel bad for myself to see disgruntle men in the class who drink alcohol and misbehaving while teacher is impacting knowledge in us.” | |

| Consequences associated with substance use in the school classroom environment were aggressive behaviors and disruption of the learning environment. | |

| “The last time a teacher entered in class and a boy took the opium and drank the liquor, he started misbehaving. So when the instructor tries to put him outside, he started to fight the man and he slams the door almost to knock the instructor’s face.” | |

| “Yes, that’s the noise making people and when they take in the alcoholic drink and the drugs, they can be there and disturbing.” | |

| Students reported that their classmates intoxicated by drugs or alcohol disrupted other students’ ability to learn. | |

| “And those of you who are paying full attention to the teachers; they will decide to distract your mind from the teaching and to disturb you people.” | |

| Students in many of the focus groups described witnessing teachers as being targeted with aggressive behavior by their substance-using peers. However, it was unclear whether students were concerned about their safety or not. Students clearly described the school milieu and their learning being disrupted, and being distracted by their peers who were ‘misbehaving’. | |

| Protective factors against substance use | |

| School as a protective factor against substance use and other highrisk behaviors: Students believed that school was could serve as a protective factor against engaging in substance use. | |

| “Yes, being in school will keep me from doing these things.” | |

| As previously described substance use and truncated schooling also seemed to be associated with increased risk for other consequences such as criminal behavior (stealing/theft) as well as unplanned and unwanted pregnancy. | |

| “The people that use drugs, they don’t plan their future. Some of them pregnant people and they go and stand and say not me pregnant.” | |

| One student highlighted this by describing the protective influence of teachers and school on preventing unplanned pregnancy. | |

| “My teacher can advise me. They can say wait for your time, go to school. When God helps you and you finish school, God will give you your own partner, because when you rush sometimes people will easily pregnant you.” | |

| School was also described as an important place to learn about, HIV/AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases, and safe sex practices. | |

| “It’s (condoms) to protect you from AIDS, gonorrhea, and others. My former study class teacher taught me biology and told us about condoms.” | |

| Expulsion from school would possibly limit opportunities to educate school-aged youths about sexually transmitted diseases (STD’s) and safe sex practices. | |

| School, substance use, and the future | |

| School was also described as protective for one’s “future”, and the protective benefits of staying in school were less likely to be conferred upon students who were either expelled or who chose to drop out of school prematurely. | |

| “For example, if I’m kicked out of school, and I’m being ill-treated, I could drop out of school and find some time to take up my time and end up being on the streets, and start drinking, stealing, etc.” | |

| Students in these focus groups associated their “future” and their classmates “future” with school. | |

| As previously discussed, students felt that being in school was protective against detrimental outcomes such as continued substance use, violence and criminal behavior, as well as unplanned or unwanted pregnancy. Students also described school as a means to providing opportunities, and improving their status in life. | |

| “Yes when you want for you to go to school, you plan your future because you in your family, you want to be the head, of course you’re small but they will respect you; so long you finish with school, you working, you get money, you will see all you people coming around you.” | |

| Students who were motivated to learn felt that school was important to their future, as well as having a classroom environment conducive to learning. | |

| ”So I feel that this program is very important for us who are really willing to learn.” | |

| Collectively students viewed school as benefiting their “future” when referring to the protective as well as cultivating aspects of school. Conversely, students felt thatconsequences such as prematurely exiting school (expulsion or dropping out) or disruption of the classroomlearning environment were adversely affecting their friends’ future. | |

| “No, not because it (substance use) is causing me problem, because I am afraid because it (substance use) is damaging our friend’s future.” | |

| “It makes me to be embarrassed because young men like myself could be leaders of this country so to see them doing such things means that no one will be able to rule them in the future.” | |

Discussion |

|

| The public health impact of substance use among youth in postconflict societies, particularly Liberia, is not well understood [18,19]. Thus, we hoped to learn more about students’ perceptions regarding consequences of substance use in the school setting in Liberia using a small focus group setting. We chose a focus group methodology as a means of interviewing a small group of participants in a less anxiety provoking setting as substance use could be a potentially difficult-todiscuss topic [15,16]. Other studies using focus groups have found this method to be effective in soliciting a richer and more diverse participant narrative when compared to individual interviews asking similar research questions [15,16,20,21]. Qualitative studies such as this could also be helpful in developing more culturally specific and meaningful epidemiologic questions when developing larger quantitative public health research methodologies. | |

| Marit Woods wrote about the importance of incorporating Liberian youths into the post-conflict reconstruction efforts, a position subsequently echoed by Liberia’s president [4,22]. The importance of well-educated youths to the country’s post-conflict recovery, and potential implications for other countries with a similar geopolitical and socioeconomic make-up makes understanding the consequences and impact of substance use among youths attending school in Liberia a germane focus of study.In this study, students from three public schools in Monrovia, Liberia described four themes associated with substance use in the school setting – behaviors, consequences of substance use affecting individuals using substances, consequences of substance use affecting those proximate to the substance-using individual within the school milieu, and the school environment as a protective factor. | |

| Although there is a large amount of data published on the consequences of substance use among adolescents and young adults globally, there is very little data regarding the contextual and cultural variables of substance use in Liberia, particularly in relation to Liberia’s post-war status [19]. For example, students often used culturally specific phrases and idioms of distress when describing behaviors or consequences related to substance use in the school setting. The term ‘weesie’ referred to getting high or becoming intoxicated, and the phrase ‘it becomes a part of you’ seemed to refer to symptoms of addiction. The term ‘opium’ was often and somewhat confusingly used as a synonym for marijuana, which is documented in other studies as well [18]. Therefore, understanding how culturally specific expressions, local customs, and attributions shape perceptions of behaviors and consequences is critical to developing relevant epidemiologic tools to better understand such behavior as well as developing meaningful strategic interventions [23,24]. | |

| In many African countries youths tend to be marginalized, which further exacerbates many socioeconomic consequences such as unemployment, exposure to violence/crime, and lack of societal engagement [22]. Indeed, study participants in these focus groups described violence, particularly sexual violence towards women, as well as other criminal behaviors such as theft in connection with substance use and truncated schooling. Importantly, students also felt that parents were unaware that substances were being concealed and brought to school, which is perhaps a reflection of lack of parental and family involvement. | |

| In this study, substance use in the school setting was associated with important individual consequences, such as intoxication, risk for developing addiction, misbehavior and confrontations with the teacher, and decreased motivation to attend school which in turn led to premature exiting from school, and increased risk for engaging in deviant behaviors. Conversely, students perceived that school was protective against violence and juvenile delinquent behavior. These findings are supported in the literature that describe actively engaged families along with high academic achievement, and motivation to learn in school, as being important protective factors against juvenile delinquent behavior [25]. The latter findings are particularly important, in that they support the importance of a school classroom environment that is safe and conducive to learning, something that students also described as being adversely affected by substance use in the school setting. | |

| Individual consequences associated with substance use in the school setting seemed to begin with clearly described behaviors associated with substance use which involved students concealing substances and alcohol and bringing them to school. Students described concealment of substances in their school bags, or mixing opium in with popular snack items such as kanyan or various beverages including juice and tea. Students described one instance where a ‘gate man’ or school security officer seemed to be aware of this behavior and allowed students outside to use the substances, but no indication of consequences was mentioned in that particular narrative. In private schools, students were described as using substances in school and bribing teachers to avoid consequences. Students also described being wary of consuming kanyan or juice at school out of fear that they may unknowingly ingest a snack item mixed with opium or other substance and become intoxicated even as early as elementary school. What was unclear is how common such behavior was, and to what degree this behavior was viewed as socially and culturally normative by students and school officials. These are important research questions for further study. | |

| Students described various reasons for bringing substances to school ranging from helping them to overcome social anxiety to selftreating mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression. PTSD and major depression are common conditions connected with witnessing or being associated with atrocities of past conflict [26]. In some cases students made reference to some of their classmates serving as “child soldiers”, where substance use was very common in programming and desensitizing these individuals [27,28]. Other students simply indicated that they wanted to “disturb” the class and confront their teachers. Whatever the reason for bringing substances to school a direct consequence of this behavior described by students was either knowingly or unknowingly becoming intoxicated. | |

| Previous research has found that substance use and intoxication from alcohol and cannabis in the school setting is associated with a number consequences including increased likelihood of heavy drinking over time, increased rates of school dropout, increased highrisk behaviors, and decreased development of positive peer relationships [25,29]. We did find that substance use among schoolaged youths was associated with choosing to drop out of school, whether due to development of addiction, or lack of motivation, or some combination of factors. Students described high-risk behaviors associated with truncated schooling such as increased sexual behaviors and unplanned or unwanted pregnancy, which was consistent with other studies [30]. Students discussed their concerns that intoxication from alcohol and substance use led to changes in their classmate’s behavior, disruption of the classroom setting, and that alcohol and substance use was associated with suspension/expulsion or dropping out of school. | |

| Disruption of the classroom setting and subsequent mandatory interruption of school attendance or removal from school altogether are important consequences that have individual, environmental, work force, and societal ramifications [5-7,25]. In this study, students described substance-use related disruption of the classroom setting as having both individual as well as classroom milieu consequences. Students cited disruption of the classroom setting as a reason for discipline from the school including suspension or expulsion. Students described different examples of intoxicated students who would confront teachers in school, which led to suspension or expulsion from school. Teachers were not interviewed to learn about their perspective when intoxicated students confronted them, as this was not the focus of our study, but would be important for future studies. | |

| Other forms of intervention for managing disruptive students included transferring a student to a different school. This was also associated with the socioeconomic disparity among public school students with more affluent students tending to be transferred to private schools, and other students simply being expelled from school. This may reflect general uncertainty as to how best to respond to the disruptive student especially when associated with alcohol or substance use. | |

| Expulsion of students of privilege, students whose parents were sufficiently affluent enough to send them to private school, who were using substances was not only viewed as an ineffective individual consequence but in fact seemed to enable the behavior, and in some cases placed the individual at increased risk for addiction with recurrent substance use, as private schools were viewed as more accepting of student substance use. Conversely, expulsion of students of lower socioeconomic status could place school-aged youths at increased risk for violence and other consequences associated with substance use on the streets, in addition to the individual consequence of halting that student’s schooling. | |

| Suspension, expulsion, and dropping out of school are all particularly concerning consequences due to the high rates of unemployment among Liberian youth and the vital role that education could play in improving the post-conflict Liberian economy. In this study, students believed that alcohol and substance use occurred frequently on school campuses, although our study design did not allow us to quantify this perception. Students also believed that peer alcohol and substance use was adversely affecting their future. Students also clearly describe school milieu consequences such as disruptive behavior secondary to peer alcohol and substance use. Specific consequences described by students included decreased quality of learning, and confrontations with school teachers. | |

| This is a challenging dilemma without an easy solution. In other countries brief school based interventions for substance using adolescents have been trialed with mixed results [31]. This study was not designed to determine the frequency of school suspension, expulsion, or dropouts associated with alcohol or substance use, which would be an important follow up research question. Another significant concern is how these disruptive behaviors affect the quality and safety of the school environment, and the impact this has on education and the future of young people who are motivated to learn. Previous studies have cited poor quality of school environment and lack of schoolteachers as important school-related factors that influence poor attendance among Liberian school students [32]. | |

| Students had some sense that alcohol and substance use in school was affecting their future, which may be a protective factor. Student engagement could serve as an impetus for school students to become actively involved in developing strategies and interventions to reduce alcohol and substance use in the school settings. What is unclear from this study is the importance of alcohol and substance use in school settings relative to other challenges school students in Monrovia face. | |

Limitations |

|

| This was a relatively small, qualitative study that used focus groups to gather information about important themes related to substance use in the school setting from public school students in Monrovia, Liberia. As described in other qualitative studies strength of opinion was difficult to determine within focus groups as solicited opinions are context-specific and may not accurately reflect how strongly held a particular belief is [18,19]. Larger and more targeted epidemiologic studies are needed to confirm these results and identify strategies for further education about substance use in West African schools, promote harm reduction, and reduce substance use in the school setting are needed to confirm and expand on the results reported in this study. Additionally, this study was not designed to detect the frequency of behavior or consequences associated with alcohol or substance use among school students, and as such we attempted to highlight important follow up research questions raised by this study throughout the discussion. | |

| One of the challenges of cross-cultural research is obtaining data that is both accurate and meaningful to the country and culture of study. Although there have been numerous studies investigating substance use among youths in the school setting world-wide, there is a paucity of data among Liberian schools and students. While this highlights the importance of studies such as ours, it is also akey limitation when attempting to make inferences from other studies and applying them to our cohort population. | |

| We also note that for purposes of standardization world bodies such as WHO, United Nations (UN), and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) collectively use the term ‘youth’ to refer to persons ages 15-24, although individual societal variation of the term ‘youth’ is commonly recognized [5,33]. Our group of study participants ranged in age from 12-20 approximating the standardized age range of the term ‘youth’. Developmentally speaking the term ‘youth’ was intended to capture a cohort of persons who fall between the life-stages of leaving mandatory education and first becoming employed [33]. We have used the term ‘school-aged youths’ as this was the developmental categorization that best described our study participant cohort, but recognize that this may be a potential limitation when comparing this study to other studies using the term ‘youths’. | |

Conclusion |

|

| A better understanding of important themes associated with substance use among Liberian school-aged youths and how they affect individuals and the school environment is critical to developing public health strategies to address this issue. This study highlighted important behaviors and consequences of alcohol and substance use among school students in Monrovia, Liberia, and underscored the importance of school as a protective factor that is important for the future of young people. This study provides a further understanding of the important problem of substance use, and may lead to the development of appropriate and meaningful intervention strategies in Liberia, and could have implications for other countries with similar profiles. | |

Acknowledgement |

|

| The corresponding author is supported by a NIH grant (#5K01MH100428). | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi