Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 9 Issue: 3

A Study on Psychological Traits of Long-Term Fieldworkers

Yasuo Kojima1*, Kohske Takahashi2, Naoki Matsuura3 and Masaki Shimada4

1School of Psychology, Chukyo University, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan

2College of Comprehensive Psychology, Ritsumeikan University, Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

3Department of Human Relations, Sugiyama Jogakuen University, Nisshin, Aichi, Japan

4Department of Animal Sciences, Teikyo University of Science, Tokyo, Japan

*Corresponding Author: Yasuo Kojima,

School of Psychology, Chukyo

University, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan

E-mail: ykojima@lets.chukyo-u.ac.jp

Received date: 17 August, 2023, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-112793;

Editor assigned date: 21 August, 2023, PreQC No. IJMHP-23-112793 (PQ);

Reviewed date: 04 September, 2023, QC No. IJMHP-23-112793;

Revised date: 14 September, 2023, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-112793 (R);

Published date: 22 September, 2023, DOI: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000233

Citation: Kojima Y, Takahashi K, Matsuura N, Shimada M (2023) A Study on Psychological Traits of Long-Term Fieldworkers. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 9:3.

Abstract

Based on interviews with researchers with long-term overseas fieldwork experience, we examined the psychological characteristics that make such fieldwork possible. The study conducted interviews with 10 mid-career researchers in their 30s to 50s in various disciplines, such as zoology, anthropology, and ecology, where fieldwork is frequently undertaken on an individual basis. Afterward, we conducted a qualitative analysis of their narratives. The results led to six major categories encompassing 35 and 19 small and medium categories, respectively. Co-occurrence network analysis based on the small categories that appeared in the narratives of at least three participants and with a frequency of occurrence of at least five pointed to six separate cohesion groups. Experiences unique to fieldwork were extracted such as the assumption that unplanned events may occur, the ability to enjoy local lifestyles and relationships with people while receiving support, and the feeling that can only be experienced by crossing a boundary into a world that is overwhelmingly different from one’s everyday life. Moreover, the results indicated that years of fieldwork experience may influence values and attitudes as well as the manner of engagement in interpersonal relationships.

Keywords: Fieldworker; Psychological traits; Semi-structured interview; Qualitative Study; Co-occurrence network analysis

Introduction

Within the humanities and social sciences, various research methods are used. One of these is the fieldwork approach, in which researchers visit a site, intensively examine the local culture and environment, and collect data. Marinowski a leading anthropologist, pioneered the methodology of fieldwork in the New Guinea

Trobriand Islands, where he developed a method known as participant observation, which remains the standard method of research among anthropologists today [1]. He identified three major characteristics of participant observation, namely, active engagement in the social life of concern, direct observation of life within a society, and inquiry into the social life of a subject. The essence of anthropology denotes staying in a local area for relatively prolonged time periods, overlapping oneself with the people living as well as carefully maintaining objective perspectives, and elucidating locally specific rituals, behavioral patterns, and the cognition of the people behind them. In anthropology, several books address the outlines of research methods and pointers in field research [2-4]. These books provide valuable guidance for beginning scholars from entry into the field to establishing rapport, addressing culture shock, identifying research questions, using techniques for interview and observation, taking notes, compiling data, and observing ethical considerations.

Notably, fieldwork is not limited to anthropology but is widely implemented in other academic domains that mainly involve staying in the field and collecting data. A few representative fields include biology, ecology, archaeology, geology, and political science. Particularly, ethology emphasizes the observation and recording of populations of animals living in their natural habitats to understand their real appearance from an ecological viewpoint. Thus, scholars emphasize capturing natural ecology, which differs from that in artificially created environments such as zoos. Thus, fieldwork is of great significance in meeting this role. Nevertheless, the common characteristics of fieldwork are that it involves staying in a specific region for a given period, engaging in themes and subjects that can only be observed and experienced at the site, and collecting and publishing research data accordingly.

As fieldwork is frequently conducted over a period of weeks, months, or even years, it imposes substantial mental and physical strains on researchers. The majority of fieldwork is conducted outside one’s country, which requires researchers to spend prolonged periods in environments that physically, socially, and drastically differ from those of their origins. In other words, researchers may be extremely deprived of routine and familiarity. Unsurprisingly, this scenario leads to more stress than one would expect, which leads to a major challenge for fieldworkers in terms of appropriately coping with stress. Additionally, researchers in the field are frequently exposed to situations that largely differ from those they originally planned; as such, scholars expect that numerous occasions may emerge when they will have to act through trial and error and rely on intuitive judgment at times.

Another significant element of fieldwork is the large amount of money required for a long-term stay. In addition, researchers who conduct observations of wildlife in forests, savannas, and other locations must also spend considerable money to hire local rangers (assistants) who are familiar with information on the free-ranging areas and migration routes of animals, as well as their seasonal variations, and the environmental and geographical conditions in the surrounding areas. Given the substantial cost of research, researchers undergo intense pressure to return to one’s country with a worthwhile outcome.

As previously mentioned, fieldwork studies are frequently conducted over long periods of time and are far removed from daily life physically, culturally, and environmentally. Thus, researchers are exposed to situations in which plans frequently do not proceed as expected; thus, acquiring specific skills and stress coping strategies is necessary. However, the literature that describe fieldworkers maintain their physical and mental wellbeing under these conditions and their experiences is lacking.

When fieldwork is considered in a broad sense, fieldworks in a few areas are typically conducted in groups, such as astronautics, Antarctic exploration, and archaeological and geological research, which will be discussed later. Other fields are more likely to be conducted by individuals, such as anthropology and the wildlife research described thus far. Especially in the latter, researchers are required nearly all aspects of fieldwork independently, including modifying research plans, establishing and maintaining relationships with the local people, and addressing any problem. Evidently, although obtaining advice from experienced colleagues, listening to their experiences, and reading certain books to obtain a given amount of knowledge are possible options, gradually developing one’s unique methods for addressing various circumstances and developing one’s skills through repeated stays are more likely tendencies.

Thus, this study aims to elucidate the adaptation of fieldworkers to life in the field, their experiences, and learning from their experiences, by interviewing fieldworkers who mainly conduct fieldwork on an individual basis. The participants include anthropologists, biologists, and ecologists; whenever possible, the study highlights their similarities and differences.

In addition, we focus on the mental health of astronauts, Antarctic explorers, and journalists who engage in reporting on politically unsettled areas, whose work requires them to be in harsh environments that significantly differ from everyday life for prolonged periods of time. For example, Kanas et al., conduct an experiment simulating a rocket and find that it can reduce cognitive function, cause depression and emotional instability and may lead to human error, which frequently result in serious accidents [5]. In studies that intend to measure physiological function, exposure to enclosed spaces causes increases in cortisol, epinephrine, and other hormones, which suggests that it can lead to a substantial amount of stress [6,7]. Relatively similar findings are reported in studies of individuals who have undertaken Antarctic expeditions. For example, Zimmer et al., conduct a meta-analysis of previous studies on individuals with experience of prolonged stays in polar regions and observe negative effects, including reduced psychophysiological and cognitive functioning, mood disorders, and problematic interpersonal relationships [8]. Furthermore, in the field of political science, scholars point out that they may go to work in war zones and other areas for coverage, which may cause burnout, and that peer support networks can be effective in regulating emotions and stress under these circumstances [9].

Many studies that address the psychological experiences associated with fieldwork focused on topics such as depression and anxiety due to stress and how to cope with them. However, others have noted the positive contributions of fieldwork. In this regard, John et al., summarized the experiences of fieldworkers in the field of geology and remarked on the potential for fieldwork to promote human development [10].

Extensively, reports emerged on the benefits of long-and shortterm overseas field experiences on participants. For example, Phillips et al., demonstrated that fieldwork experiences can contribute to fostering mental flexibility and teamwork, among others [11]. Meanwhile, studies in Japan have endeavored to incorporate the accumulation in anthropology and other fields of study into a program for overseas experiences as part of university classes, which Konno refers to as field education [12]. Kobari has analyzed reports of students who participated in an overseas educational program and revealed that they experienced various peculiar emotions (e.g., fun, gratitude, surprise, sadness, and stress), recognized the insufficiency of experience and knowledge, viewed Japan from a comparative perspective, gained new perspectives, and obtained opportunities for self-reflection during their stay [13]. In addition, Wakabayashi et al., have investigated the impact of short-term overseas participatory learning (overseas field study) in graduate schools on the career development of participants [14]. The authors have suggested that the program promoted awareness of the importance of teamwork and contributed to the enhancement of multifaceted perspectives and communication skills required for acceptance in an internationally oriented society. In addition, Yakushiji has suggested that spending time in a remote and foreign country, especially in a developing country, could provide various benefits [15]. One of these is an educational experience that fosters a sense of responsibility and understanding of problems, such as poverty, and challenges to development and gender issues. Furthermore, doing so could also lead to self-discovery and personal growth. In Japan, Yabuta et al., among others, have made similar attempts [16-18]. These authors also reported substantial effects on cognitive, knowledge, mental, and behavioral aspects. As previously mentioned, several studies have been conducted on the challenges encountered by researchers and professionals during long-term stays in unusual environments, including those in spaces and in Antarctica, as well as by journalists in countries with political instability. A few efforts have been exerted to examine the forms of stress associated with such stays and the acquisition of skills necessary to conduct work. Others have examined the experience of staying abroad for a few weeks as an educational or enlightening activity and have attempted to implement it in practice. However, few studies have been conducted to clarify issues such as the so-called experience of fieldworkers in general and the consequences that these experiences may yield. We believe that the findings of these studies will provide a valuable insight for those who intend to undertake fieldwork in the future and will serve as guidelines for people in terms of the skills necessary for maintaining positive mental health and for coping with stress.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants in the interviews were 10 researchers whose ages ranged from 30s to 50s. Initially, the first author asked an acquaintance to introduce a middle-aged fieldworker who had been conducting an overseas observational study on certain wild animals for interview. She was then asked to successively introduce other acquaintances who were also fieldworkers (i.e., the so-called snowballing method) to invite more collaborators. When asking them to introduce participants for the interviews, special precautions were taken, such that the locations and expertise of the researchers would not be biased. The disciplines of the 10 participating researchers (male: 7; female: 3) were anthropology (n=5; Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia), zoology (n=4; Africa, Southeast Asia), and entomology (n=1; Southeast Asia). All of them had multiple experiences of conducting research in the field over a period of three months or longer.

Procedure: The first author visited the workplaces or other related facilities (e.g., universities and research institutes) of the participants and conducted in-person semi-structured interviews. An interview guide was arranged such that fieldworkers in their respective specialties could easily respond to the questions. The guide was structured on the basis of the suggestions of the third author, who specializes in anthropology, and the fourth author, who specializes in zoology.

The topics of the interviews consisted of motives for deciding to conduct fieldwork, experiences during the first fieldwork trip, lifestyle in the field (e.g., typical daily schedule, meals, and relationships with the local people), management of physical condition, overall psychological state, stress and coping, characteristics necessary for fieldworkers, and perceived changes through their fieldwork experiences. The interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants. The average duration of the interviews was 89.5 min (range: 75-122 min).

Ethical considerations: The present study was conducted in terms of the principles of the revised Declaration of Helsinki. Also, the present study was approved by Chukyo University Ethical Review Committee (Rinshin 21-013). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before enrollment in the study.

Analyses: The first author transcribed and labeled all recorded data in a manner similar to the Jiro Kawakita (KJ) method with careful attention to the accurate reflection of the descriptions of actual narratives apart from small talk [19,20]. At the outset, 1,650 data were labeled; after a close scrutiny, however, data that were deemed less relevant to the theme of this study were excluded. Eventually, the study extracted 565 labels, which were used for analysis.

The first author then grouped the labels into categories (small), which were further combined into high-level (medium) categories. A few of the data under the medium categories were further aggregated into high (major) categories.

The second author then checked the aggregation process from the original labels to the small, medium, and major categories, and discussed with the first author to adjust the issues that the second author deemed problematic in the aggregation process and the category names. Thereafter, an undergraduate student, who had been well trained, conducted the task of dividing all labels under the categories independent of the first and second authors. At this point, the agreement rate between the classification of the first and second authors was calculated at 63.8%. The first author reconfirmed where a disagreement existed in the classification and discussed it with the student concerned. Thus, the final categorization was completed.

In the analysis, the number of utterances that correspond to the major, medium, and small categories was calculated for each participant, and a co-occurrence network analysis was conducted to evaluate the degree of co-occurrence between the categories, as described below. A KH coder was used as the analysis software [21,22]. The KH coder is text mining software developed by a Japanese researcher that specializes in sociological surveys and is used for empirical studies in many research fields in Japan and overseas [23-26].

Results

Categories derived from the interview data

Table 1 depicts that the study obtained six major categories with the first four major categories containing seven, five, two, and five medium categories, respectively. In addition, a few of these medium categories contained smaller subcategories.

| Level of categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Medium | Small | No. of participants with narratives |

| Issues, coping, and interpersonal relationships specific to field research | (1) Unplanned events | 7 | |

| (2) Arrangements and attitudes in conducting the research | (a) Acting without planning in advance, (b) Behavior reflecting his/her attributes, (c) Being well prepared, (d) Just trying things out, (e) Long-range planning, (f) Letting things happen, (g) Sense of getting by, (h) Persistence and stepping ahead, (i) Never giving in, (j) Never overreach, (k) Never do anything reckless, (l) Responding flexibly | 10 | |

| (3) Data collection and analysis | (a) Recording and analyzing by trial and error, (b) Keeping a steady record | 9 | |

| (4) Impatience and sense of urgency | (a) Impatience and frustration due to a feeling of uncertainty, (b) A sense of urgency to accomplish something | 6 | |

| (5) Everything is within one's competence, responsibility, and discretion | 4 | ||

| (6) Appropriate distance and relationship with colleagues and research associates | 3 | ||

| (7) Transfer to a new field/theme | 6 | ||

| Life in the field and relationships with the local people | (1) Compatibility with the field | 2 | |

| (2) Blending, harmonizing, and deepening | (a) Participation in local events, etc., (b) Enjoying interactions with and receiving support from local people, (c) Becoming familiar with and accepting the local people and lifestyle | 9 | |

| (3) Negotiation and addressing troubles with assistants and/or informants | (a) Negotiation, (b) Trouble with local people | 6 | |

| (4) Schedule and lifestyle management | (a) Comfort with regularly scheduled life, (b) Enduring and enjoying spare time | 6 | |

| (5) Stress and stress management | 10 | ||

| Temporary crossing between the real world and other worlds | (1) Crossing between the real world and other worlds | (a) Crossing boundaries, (b) Homesickness, (c) Want to stay more | 7 |

| (2) Limited period of time | 2 | ||

| Real pleasure from/motivation for fieldwork | (1) Real pleasure of fieldwork | (a) Feeling of being alive, (b) Enjoying interactions with people from other disciplines, (c) Joy of encountering unanticipated things, (d) Confidence through accumulation, (e) Unique feelings and behaviors while in the field | 7 |

| (2) Affirmative look at past fieldwork | (a) Positive reflections on the initial visits, (b) Forgetting unpleasant memories | 6 | |

| (3) Want to know myself | (a) Knowing myself, (b) Myself as an Outsider | 4 | |

| (4) Want to see another or unknown world | 6 | ||

| (5) Additional value apart from data collection | 2 | ||

| Personal change through fieldwork | 10 | ||

| Suitability for fieldwork | 10 | ||

Table 1: Categories derived from the interview data.

Issues, coping, and interpersonal relationships specific to field research

Unplanned events: Seven of the interviewees mentioned that in their field studies, a lot of events deviated from their plans. One of them said, “I had heard from some of my senior colleagues that things did not go as planned, but I did not expect this much” (zoologist, MB). Another said that, “I entered the field after a certain amount of planning, but I had heard from my senior colleagues that everything could completely fall apart” (anthropologist, AZ).

Arrangements and attitudes in conducting the research: This medium category included 12 small subcategories. As for (a) Acting without planning in advance, other comments were, “I didn’t have a plan for how I was going to spend my days, it was almost haphazard” (zoologist, TK) and “I really relied on chance throughout the research” (anthropologist, NZ). (b) Behavior reflecting his/her attributes was related to the pursuit of research activities while taking advantage of personal features such as being Japanese or a woman. The representative narratives were: “The appearance of the Japanese people is good for fieldwork. We are seen as young, so we are less likely to be cautious. This was very helpful” (anthropologist, AZ), “(I am a woman, so) it was hard to be cautious. Men who were doing fieldwork in the same places were more likely to be suspicious” (anthropologist, NZ). In terms of (c) Being well prepared, one of the participants stated, “I had read many articles, so when I noticed a certain behavior (of the target animal), I thought, ah, I’ll attempt to use this topic” (zoologist, SI). Regarding (d) Just trying things out the comments were, “I like talking to various people, and I always have the spirit of going to various places and seeing everything” (anthropologist, SN) and “I thought I could probably get this data here based on some past papers, so I just tried the same thing out for now” (zoologist, SI). With respect to (e) Long-range planning, a few of the participants expressed that, “With three months to go, I can roughly plan out my schedule, and then I’ll follow it” (zoologist, TK). Many of the participants (n=6) mentioned (f) Letting things happen: the typical statements were, “I didn’t necessarily decide to go to that research field, it was just someone who gave me the opportunity to go there in the beginning and I found myself there” (anthropologist, NM), “Working hard doesn’t always produce good results. It may be rather better to be passive” (anthropologist, NZ). In terms of (g) Sense of getting by, the participants said, “I think I’ll get help from someone somewhere. I thought it was something like that” (zoologist, TK), and “I didn’t really have an idea of anything, but I just thought that with this data, I might be able to do something after returning back home” (anthropologist, NZ). For (h) Persistence and stepping ahead, the narratives were, “Even if I think it is dangerous, I will try until the very last minute” (zoologist, NB) and “Even if I have an appointment at 6 a.m. the next morning, I will never leave if I think there might be some interesting stories later” (anthropologist, AZ). In terms of (i) Never giving in, one participant said that, “It’s tough, but I felt I had to get results here at all costs” (anthropologist, AZ). For the category (j) Never overreach, the participants stated that, “If I even think for a second that it would be bad if I would fall off or get lost and the sun would set, I will quit” (zoologist, MT) and “I wonder how far I would go with it. Somewhere you have to give up” (anthropologist, AZ). In (k) Never do anything reckless, the interviewees expressed the following, “I think I judged that I would not do anything risky at first” (zoologist, MT). Finally, regarding (l) Responding flexibly, the narratives were, “When I go to a field site and think that there is no possible way but to do things this way, I do so. Of course, I have a plan, but if I think it is impossible, I change it there and then” (ecologist, HS), “When I couldn’t carry out the research, I analyzed the data and sorted out the photos I had taken” (zoologist, NB), and “If my attitude becomes rigid, it is difficult to control the situation. If I don’t respond flexibly, then it is mentally hard for me and causes trouble for other people” (anthropologist, NM).

Data collection and analysis: This medium category included two smaller subcategories. The first is (a) Recording and analyzing by trial and error with the following typical narratives. “I was never taught how to collect data manually. I learned everything by watching and learning, and eventually I did it on my own” (anthropologist, SM), and “My academic advisor used time sampling methods, so I tried it myself, but I had to think about the details in the field and make adjustments on my own” (anthropologist, SN). The second is (b) keeping a steady record: “I followed and recorded the target individuals diligently. I rarely observed interesting behaviors, but I kept on recording” (zoologist, SI), and “If you keep on observing and recording without laziness, you will encounter some interesting experiences” (zoologist, MT).

Impatience and sense of urgency: This included two smaller subcategories, (a) Impatience and frustration due to a feeling of uncertainty and (b) A sense of urgency to accomplish something. Example comments of the first are: “When I was not able to observe XX (target animal) for a whole month, I was really upset” (zoologist, TK) and “I always felt like I didn’t know what or how things were progressing” (anthropologist, NZ). For the second, an example is as follows: “I was under pressure to achieve something” (zoologist, MT).

Everything is within one’s competence, responsibility, and discretion: The narrative that represents this category is as follows: “I think that if I don’t do anything within my ability in the field, then it will be my own life and the other people will also be at risk” (zoologist, TK).

Appropriate distance and relationship with colleagues and research associates: Those that fell under this category included: “Sure, there are times when I want to be alone, but when I feel that way, I can be alone in the woods” (zoologist, MT) and “I have no problem staying in the field with other people” (anthropologist, SM).

Transfer to a new field/theme: The narratives that corresponded to this category were: “I am rather easily bored; after two years in the field, once I got a sort of feel for it, I lost the sense of freshness” (anthropologist, NM), and “I have little attachment to a certain field” (zoologist, NB).

Life in the field and relationships with the local people

Compatibility with the field: Two participants discussed about compatibility with the field: “I am not sure if I can have fun anywhere” (ecologist, HS), and “It is very important that you feel comfortable or not when you visit somewhere” (anthropologist, NM).

Blending, harmonizing, and deepening: This medium category contained three smaller categories under it. As for (a) Participation in local events, etc., “I was invited many times to attend local events in the village. It was great that I could ask for help when I needed it” (ecologist, HS), and “There was a religious meeting once a week, and I attended that meeting as much as I could” (anthropologist, AZ). Seven of the participants mentioned (b) Enjoying interactions with and receiving support from local people: “I learned from the local people to climb trees up by using a machine” (Zoologist, NB), “Everyone in the village is very kind and helps me out. Even if I didn’t understand their language immediately, I could live without much inconvenience” (anthropologist, SN). In addition, eight participants mentioned (c) Becoming familiar with and accepting the local people and lifestyle: “I was delighted to eat food prepared by the wife of the local assistant” (zoologist, SI), and “I felt like I was attuning to the local way of living and interacting with people” (anthropologist, NZ).

Negotiation and addressing troubles with assistants and/ or informants: Two subcategories emerged. (a) Negotiation was discussed in the following narratives: “When the assistant came late at the appointed time, we made an arrangement to extend the working time to the afternoon” (zoologist, SI) and “This is as far as we can ask local informants to go” (anthropologist, AZ). For (b) Trouble with local people, one participant said, “Since I am a complete stranger, there were some cases in which relationships with local people became strained in ways that I could not have imagined” (anthropologist, AZ).

Schedule and lifestyle management: Two smaller subcategories were observed. The first was (a) Comfort with regularly scheduled life with specific narratives such as, “I get out at a certain time every morning, find YY (target animal), collect data, and then go to bed at night, healthy, right after dinner” (biologist, SI). The second was (b) Enduring and enjoying spare time: “When I have no work to do, I can spend it relaxing, not rushing around” (biologist, TK).

Stress and stress management: In long-term fieldwork, the participants exhibited various strategies for stress and stress management: “It was stressful because I could not be alone” (anthropologist, NM) and “I seriously had trouble with food” (anthropologist, NK). Regarding stress, the participants mentioned many types: “I really felt lonely when the research was not going well” (zoologist, SI), “The place I lived at was full of cracks. People were always peeking in on me since I was an outsider” (zoologist, SI), “It was stressful not to be alone” (anthropologist, NM), “I really had trouble with food” (anthropologist, NK), and “It was tough because there was absolutely no way of communicating with Japan” (zoologist, TK). In addition, their narratives for stress management were as follows: “I tried to take a rest at a predetermined time. For example, I always took a nap” (ecologist, HS), “I would make a place where I could escape. When things were tough, I would leave the research site and stay there for about two weeks” (anthropologist, AZ), “It is important to be aware of what condition I feel comfortable in” (zoologist, TK), and “At the end of each day, I would write a mark on the calendar to mark off my feelings and keep myself motivated again tomorrow” (anthropologist, SN). Each participant cited unique strategies for managing mental health that is, maintaining a stable mental state.

Temporary crossing between the real world and other worlds

This category was composed of two medium categories, as follows.

Crossing between the real world and other worlds: This included three smaller subcategories. The first is (a) Crossing boundaries: “After passing through the security and departure gate, my mind is set. I think I have to move on” (biologist, TK) and “I don’t like going to the field with ease. It’s sort of like a ritual to arrive at the field after being on the bus for hours” (anthropologist, NM). For (b) Homesickness, one participant said that, “I always think I am alright after I know that I can go home” (anthropologist, SN). In addition, the participants expressed their feelings, such as “I was counting down the days until I had to leave, I was so lonely” (biologist, SI) and “I felt like it was a long summer vacation while I was over there” (ecologist, HS), for (c) Want to stay more.

Limited period of time: The comments related to this category are, “If there is no end, certainly you may not have the mental health to keep going” (anthropologist, SN).

Real pleasure from/motivation for fieldwork

This major category obtained four medium categories as follows.

Real pleasure of fieldwork: This included five smaller subcategories. First, for (a) Feeling of being alive, one participant (biologist, SI) said, “When in the field, I can truly feel that I am actually alive” (biologist, SI). In (b) Enjoying interactions with people from other disciplines, the following comments emerged: “There were researchers from other countries in the same place. I found it fascinating to talk with them, who were in completely different academic backgrounds. I was surprised that they have totally different interests though they were the similar age as me” (biologist, NB), and “When talking with people in other specialties, it was fun that the topics jumped to totally unexpected topics” (anthropologist, SM). For (c) Joy of encountering unanticipated things, the common comments were, “The most exciting thing in fieldwork is when I see unexpected things for the first time” (zoologist, TK) and “It was intriguing to describe the world that only I know, and to report it” (anthropologist, NM). As for (d) Confidence through accumulation, one participant commented that, “It seems to me that a series of small successful experiences have built up a sense of confidence” (anthropologist, SM). With regard to (e) Unique feelings and behaviors while in the field, the participants stated that, “When in the field, I am very enthusiastic. Once I get to the research field, I do greet all the inhabitants of the village each time I see them” (biologist, TK), and “I am there with my eyes on various things, keeping a certain amount of tension” (anthropologist, SN).

Affirmative look at past fieldwork: This category is concerned with the positive perception of the participants about their initial fieldwork experience and consists of two medium categories. The first was (a) Positive reflections on the initial visits with specific narratives such as, “At that time, I felt that every day was very fulfilling” (biologist, SI) and “I thoroughly enjoyed my first stay” (anthropologist, SN). The second was (b) Forgetting unpleasant memories, in which a participant said, “I probably had feelings of loneliness, but I can’t actually remember them” (biologist, MT).

Want to know myself: This category presents two small subcategories under it. In (a) Knowing myself, the narratives were: “I feel like doing fieldwork to understand who I am” (biologist, TK) and “I would rather like to know others, but that in turn means knowing myself” (anthropologist, NM). For the second one, (b) myself as an Outsider, one of the participants said, “I am at the side watching the counterpart, but at the same time we are at the side of being watched. From the very moment we wake up in the morning, children are watching us from the outside wall” (anthropologist, NM).

Want to see another or unknown world: Example comments under this category are as follows: “It was so appealing to me at that time to go where nobody had gone before” (biologist, TK), and “I have been continuing (fieldwork) because I have a simplistic feeling of wanting to see a different world” (anthropologist, SN).

Additional value apart from data collection: For this category, biologist TK and anthropologist AZ presented corresponding narratives. TK stated, “I always mention to my juniors that it is boring to just collect data,” and AZ mentioned that, “Fieldwork is about getting something more than just collecting data.” Although neither of these narratives specifically point to some concrete things, they seemingly indicate that fieldwork can make people aware of or be stimulated by an unknown aspect apart from the research findings.

Personal change through fieldwork

The participants mentioned that they had changed in the course of their fieldwork. To give a summary of the contents, “I have become less preoccupied with matters” (zoologist, NB), “I think I have learned to be more flexible in a positive sense. Things are just the way they are” (anthropologist, NM), “I think I have started to take one step further in interpersonal relationships” (anthropologist, NZ), “I have come to see things from a different perspective” (anthropologist, SN), and “I feel like I can now see things like Japanese peculiarities well” (ecologist, HS) are typical examples.

Suitability for fieldwork

The participants also noted references to qualifications as fieldworkers. They described the following attributes: “interested in everything” (biologist, MB), “can be absorbed in the moment all at once” (biologist, TK), and “receptive to everything” (anthropologist, SN). Regarding interpersonal relationships, they mentioned characteristics such as “enjoys being with people” (biologist, TK) and “likes to talk and is interested in other people” (anthropologist, AZ). One of the intriguing narratives was, “I find joy in being in a hard situation” (anthropologist, NM).

Correlation among utterances

Regarding the abovementioned categories, the number of corresponding narratives was counted for each participant, and their correlations were analyzed (Table 2). 5 Stress and stress management, Personal change through fieldwork, and 6 Suitability for fieldwork were excluded from the variables, because all participants reported these issues. Analysis demonstrated 48 significant correlations at the 5% level, which was close to the chance level, given the total number of combinations (903).

| Variables | 1-(1) | 1-(2)a | 1-(2)b | 1-(2)c | 1-(2)d | 1-(2)e | 1-(2)f | 1-(2)g | 1-(2)h | 1-(2)i | 1-(2)j | 1-(2)k | 1-(2)l | 1-(3)a | 1-(3)b | 1-(4)a | 1-(4)b | 1-(5) | 1-(6) | 1-(7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-(1) | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)a | -.261 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)b | .226 | .427 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)c | -.338 | .194 | -.258 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)d | -.304 | -.216 | -.195 | -.097 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)e | 0.584+ | .067 | -.208 | -.310 | -.234 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 1-(2)f | -.037 | 0.712* | 0.825** | .020 | -.025 | -.315 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 1-(2)g | .534 | .360 | .000 | -.213 | -.321 | 0.944** | -.027 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 1-(2)h | .329 | .378 | 0.702* | -.105 | -.396 | -.211 | 0.773** | .000 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 1-(2)i | .435 | .083 | 0.773** | -.231 | -.097 | -.310 | 0.646* | -.213 | 0.734* | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 1-(2)j | -.153 | .035 | -.163 | -.365 | -.276 | .196 | -.278 | .101 | -.249 | -.122 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 1-(2)k | .087 | .096 | .031 | -.230 | -.453 | .074 | .059 | .102 | .314 | .138 | 0.671* | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 1-(2)l | -.052 | -.233 | .055 | .414 | -.230 | -.301 | -.148 | -.298 | -.056 | -.083 | -.550 | -.606+ | 1.000 | |||||||

| 1-(3)a | -.268 | .482 | .476 | .000 | -.072 | -.459 | 0.687* | -.236 | 0.679* | .285 | -.427 | -.119 | .215 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 1-(3)b | .185 | .318 | 0.722* | -.294 | -.123 | .000 | .449 | .136 | .200 | .490 | .155 | .118 | -.053 | .000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 1-(4)a | .153 | 0.567+ | 0.818** | -.342 | -.258 | .118 | 0.609+ | .297 | .400 | .440 | -.015 | -.182 | .116 | .398 | 0.685* | 1.000 | ||||

| 1-(4)b | .000 | -.323 | -.250 | -.187 | -.047 | .075 | -.428 | -.026 | -.382 | -.187 | .532 | .538 | -.262 | -.553+ | .358 | -.333 | 1.000 | |||

| 1-(5) | .000 | -.073 | -.339 | -.506 | .255 | 0.612+ | -.386 | .490 | -.518 | -.506 | .520 | .273 | -.627+ | -.515 | .000 | -.129 | .431 | 1.000 | ||

| 1-(6) | -.375 | -.051 | -.191 | -.286 | -.216 | -.021 | -.337 | -.101 | -.354 | -.286 | 0.880** | 0.614+ | -.319 | -.327 | .232 | -.089 | 0.733* | .479 | 1.000 | |

| 1-(7) | -.047 | .360 | -.350 | .075 | .432 | .361 | .095 | .392 | -.102 | -.224 | -.047 | -.063 | -.611 | -.028 | -.381 | -.218 | -.290 | .344 | -.298 | 1.000 |

| Note: ** p<.01, * p<.05, + p<.10; a: Correlations among medium and smaller subcategories in major category 1 are shown; The abbreviations of the variables correspond to the categories in Table 1. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2a: Correlation among utterances.

| Variables | 2-(1) | 2-(2)a | 2-(2)b | 2-(2)c | 2-(3)a | 2-(3)b | 2-(4)a | 2-(4)b | 3-(1)a | 3-(1)b | 3-(1)c | 3-(2) | 4-(1)a | 4-(1)b | 4-(1)c | 4-(1)d | 4-(1)e | 4-(2)a | 4-(2)b | 4-(3)a | 4-(3)b | 4-(4) | 4-(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-(1) | -.426 | .326 | .223 | -.397 | .000 | .389 | -.159 | .458 | -.077 | -.291 | .235 | -.182 | .130 | -.037 | -.406 | -.130 | .025 | .085 | -.389 | -.595+ | -.389 | -.104 | .389 |

| 1-(2)a | .481 | -.342 | -.338 | .534 | -.483 | -.253 | -.301 | .123 | .523 | -.167 | -.458 | -.216 | -.253 | -.291 | .500 | -.253 | .269 | -.010 | -.268 | .348 | 0.640* | 0.561+ | .067 |

| 1-(2)b | -.195 | .080 | -.143 | -.038 | -.269 | .138 | -.254 | .326 | -.247 | -.103 | -.250 | -.065 | -.138 | -.159 | -.309 | -.138 | -.244 | .091 | -.208 | -.272 | -.138 | .111 | .000 |

| 1-(2)c | 0.872** | .040 | .498 | 0.823** | .361 | -.207 | .000 | -.365 | .041 | -.258 | 0.561+ | -.291 | .207 | -.238 | 0.647* | -.207 | -.122 | .000 | .310 | .316 | 0.620+ | .000 | -.310 |

| 1-(2)d | -.220 | -.211 | .018 | .063 | .172 | -.156 | -.064 | -.276 | .031 | 0.843** | -.047 | 0.756* | .364 | -.180 | -.349 | -.156 | .235 | .545 | -.234 | 0.602+ | -.156 | .334 | -.234 |

| 1-(2)e | -.234 | -.225 | .115 | -.371 | -.275 | -.167 | -.153 | .196 | .529 | -.208 | .075 | -.234 | -.167 | -.072 | .000 | -.167 | .523 | -.055 | -.250 | -.145 | -.167 | .134 | .375 |

| 1-(2)f | .222 | .051 | -.326 | .394 | -.418 | .158 | -.419 | .278 | -.031 | .092 | -.428 | .123 | -.158 | -.302 | .024 | -.263 | -.165 | .069 | -.394 | .195 | .368 | .548 | .000 |

| 1-(2)g | -.054 | -.309 | .010 | -.164 | -.405 | -.229 | -.298 | .185 | 0.555+ | -.285 | -.026 | -.321 | -.229 | -.140 | .128 | -.229 | .465 | -.075 | -.343 | -.075 | .057 | .298 | .300 |

| 1-(2)h | .132 | .436 | -.388 | .130 | -.465 | .563+ | -.431 | .497 | -.279 | -.140 | -.382 | .000 | -.282 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -.442 | -.277 | -.423 | -.184 | .282 | .339 | .211 |

| 1-(2)i | -.291 | .519 | -.071 | -.019 | .040 | .620+ | .000 | 0.608+ | -.287 | -.052 | -.187 | .097 | .207 | -.238 | -.462 | -.207 | -.203 | .271 | -.310 | -.406 | -.207 | .000 | .310 |

| 1-(2)j | -.276 | .051 | -.259 | -.345 | -.006 | .131 | 0.721* | .327 | .298 | -.163 | -.355 | -.123 | -.196 | -.225 | -.146 | -.196 | .295 | -.171 | .441 | -.243 | -.196 | -.236 | .441 |

| 1-(2)k | .012 | .282 | -.460 | -.108 | -.183 | .421 | .425 | .306 | -.133 | -.216 | -.359 | -.104 | -.322 | -.299 | -.166 | -.322 | -.277 | -.470 | .260 | -.254 | .173 | .060 | .260 |

| 1-(2)l | .188 | -.077 | .445 | .091 | .307 | -.312 | -.218 | -.419 | -.380 | -.388 | .544 | -.438 | .134 | 0.570+ | .299 | 0.579+ | -.354 | -.029 | .200 | -.272 | -.089 | -.554+ | -.468 |

| 1-(3)a | .287 | -.044 | -.579+ | .276 | -.542 | .076 | -.632* | .022 | -.167 | .095 | -.553+ | .107 | -.306 | .418 | .342 | .459 | -.352 | -.225 | -.459 | .234 | .459 | .399 | -.172 |

| 1-(3)b | -.370 | -.356 | -.091 | -.049 | .179 | -.264 | .242 | .000 | -.104 | -.328 | -.119 | -.370 | .264 | -.265 | -.471 | -.264 | .000 | .431 | .000 | -.460 | -.264 | -.211 | -.198 |

| 1-(4)a | -.258 | -.249 | -.145 | -.153 | -.367 | -.184 | -.290 | .294 | .193 | -.229 | -.333 | -.258 | -.184 | .053 | -.059 | .079 | .191 | .155 | -.276 | -.247 | -.184 | .042 | .118 |

| 1-(4)b | -.283 | -.272 | -.121 | -.168 | .497 | -.201 | 0.739* | -.355 | -.259 | -.250 | .091 | -.283 | .302 | -.159 | -.449 | -.201 | -.158 | .099 | .452 | -.395 | -.201 | -.443 | -.302 |

| 1-(5) | -.383 | -.368 | -.164 | -.479 | -.251 | -.272 | .167 | -.080 | .324 | .339 | -.185 | .255 | -.272 | -.215 | -.304 | -.272 | .387 | -.089 | .102 | .208 | -.272 | .218 | .102 |

| 1-(6) | -.216 | -.208 | -.327 | -.283 | .119 | -.154 | 0.736* | -.107 | .003 | -.191 | -.278 | -.216 | -.154 | -.036 | -.156 | -.014 | .003 | -.210 | 0.608+ | -.241 | -.154 | -.381 | -.021 |

| 1-(7) | .244 | -.101 | -.166 | .331 | -.304 | .040 | -.270 | .189 | 0.708* | .450 | -.290 | .432 | .040 | -.357 | .269 | -.361 | .622+ | .210 | -.542 | 0.692* | .441 | 0.772** | .361 |

| Note: ** p<.01, * p<.05, + p<.10; a: Correlations among medium and smaller subcategories in major category 1 are shown; The abbreviations of the variables correspond to the categories in Table 1. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2b: Correlation among utterances.

| Variables | 2-(1) | 2-(2)a | 2-(2)b | 2-(2)c | 2-(3)a | 2-(3)b | 2-(4)a | 2-(4)b | 3-(1)a | 3-(1)b | 3-(1)c | 3-(2) | 4-(1)a | 4-(1)b | 4-(1)c | 4-(1)d | 4-(1)e | 4-(2)a | 4-(2)b | 4-(3)a | 4-(3)b | 4-(4-) | 4-(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-(1) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2-(2-)a | -.010 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2-(2-)b | .107 | .214 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2-(2-)c | 0.834** | -.145 | .064 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2-(3)a | -.081 | -.008 | .516 | .212 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2-(3)b | -.156 | .923** | -.115 | -.196 | -.129 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2-(4)a | -.223 | .092 | .129 | -.069 | .673* | .068 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2-(4)b | -.276 | .682* | -.090 | -.285 | -.323 | .784** | .020 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 3-(1)a | .134 | -.268 | -.015 | .182 | -.209 | -.198 | -.013 | .298 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 3-(1)b | -.195 | .080 | -.143 | -.141 | -.269 | .138 | -.254 | .000 | -.027 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 3-(1)c | .188 | .117 | .917** | .112 | .595 | -.201 | .123 | -.355 | -.259 | -.250 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 3-(2) | -.220 | .292 | -.161 | -.178 | -.283 | .364 | -.223 | .184 | -.072 | .973 | -.283 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 4-(1)a | -.156 | -.150 | .268 | .319 | .841** | -.111 | .408 | -.196 | .022 | -.138 | .302 | -.156 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 4-(1)b | -.180 | -.173 | -.297 | -.343 | -.149 | -.128 | -.313 | -.225 | -.228 | -.159 | -.159 | -.180 | -.128 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 4-(1)c | .815** | -.144 | .000 | .575+ | -.241 | -.248 | -.304 | -.146 | .443 | -.309 | .000 | -.349 | -.248 | .214 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 4-(1)d | -.156 | -.150 | -.306 | -.298 | -.129 | -.111 | -.272 | -.196 | -.198 | -.138 | -.201 | -.156 | -.111 | .990** | .248 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4-(1)e | -.174 | -.265 | .116 | -.012 | .004 | -.196 | .120 | .295 | .924** | .081 | -.158 | .031 | .240 | -.225 | .146 | -.196 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 4-(2)a | -.307 | -.295 | .213 | .222 | .593+ | -.218 | .245 | -.064 | .260 | .091 | .099 | .034 | .873** | -.251 | -.325 | -.218 | .506 | 1.000 | |||||

| 4-(2)b | .156 | .097 | .401 | -.062 | .372 | -.167 | .612+ | -.294 | -.297 | -.208 | .452 | -.234 | -.167 | -.192 | .000 | -.167 | -.294 | -.327 | 1.000 | ||||

| 4-(3)a | .488 | -.201 | -.100 | .447 | -.348 | -.218 | -.386 | -.243 | .332 | .695* | -.175 | .602+ | -.218 | -.251 | .380 | -.218 | .209 | -.032 | -.145 | 1.000 | |||

| 4-(3)b | .885** | -.150 | -.306 | .834** | -.237 | -.111 | -.272 | -.196 | .242 | -.138 | -.201 | -.156 | -.111 | -.128 | .745* | -.111 | -.087 | -.218 | -.167 | .509 | 1.000 | ||

| 4-(4-) | .334 | -.052 | -.368 | .322 | -.674* | .089 | -.600+ | .157 | .336 | .555+ | -.443 | .543 | -.356 | -.346 | .199 | -.356 | .157 | -.117 | -.535 | .758* | .535 | 1.000 | |

| 4-(5) | -.234 | .580+ | -.029 | -.293 | -.275 | .667* | .102 | .932** | .529 | .000 | -.302 | .156 | -.167 | -.192 | .000 | -.167 | .523 | -.055 | -.250 | -.145 | -.167 | .134 | 1.000 |

| Note: ** p<.01, * p<.05, + p<.10; a: Correlations among medium and smaller subcategories in major category 1 are shown; The abbreviations of the variables correspond to the categories in Table 1. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2c: Correlation among utterances.

Based on the abovementioned narrative categories, the study conducted a co-occurrence network analysis to analyze the cooccurrence relationships among categories. Previous studies employing co-occurrence network analysis frequently select categories that appear in approximately 20% of the sample as variables. Thus, the categories that appeared in approximately 3 (30%) of the narratives were extracted for analysis in the current study. Analysis was conducted with 26 words that displayed a minimum number of occurrences of 5 or more (Table 3).

| Categories | Frequency of Narrative |

|---|---|

| Becoming familiar with and accepting the local people and lifestyle | 29 |

| Letting things happen | 25 |

| Negotiation | 22 |

| Unique feelings and behaviors while in the field | 18 |

| Acting without planning in advance | 17 |

| Enjoying interactions with and receiving support from local people | 16 |

| Unplanned events | 15 |

| Responding flexibly | 14 |

| Never overreach | 13 |

| Appropriate distance and relationship with colleagues and research associates | 11 |

| Persistence and stepping ahead | 10 |

| Keeping a steady record | 10 |

| Transfer to a new field/theme | 9 |

| Crossing boundaries | 9 |

| Knowing myself | 9 |

| Sense of getting by | 8 |

| Recording and analyzing by trial and error | 8 |

| Comfort with regularly scheduled life | 8 |

| Want to see another or unknown world | 8 |

| Impatience and frustration due to a feeling of uncertainty | 7 |

| Never do anything reckless | 6 |

| Enduring and enjoying spare time | 6 |

| Positive reflections on the initial visits | 6 |

| Being well prepared | 5 |

| Never giving in | 5 |

| Joy of encountering unanticipated things | 5 |

Table 3: Narratives with high frequency.

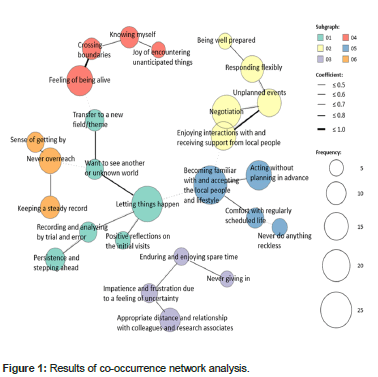

Jaccard coefficients greater than or equal to 0.2 were used to examine associations among words, and a minimum spanning tree was drawn (Figure 1). The study employed the random walks method to detect clusters of strongly connected words (subgraphs) [21]. In the diagram, stronger co-occurrence relationships are drawn with thick lines, and more frequently occurring words are depicted as large circles. Connections within the same subgraph are drawn with solid lines, and those between different subgraphs are drawn with dotted lines.

The subgraphs were grouped into six categories. The first contained the category Want to see another or unknown world, which was associated with the second highest number of occurrences overall, Letting things happen (0.71) and Transfer to a new field/ theme (0.71, values enclosed in parentheses are Jaccard coefficients). In addition, letting things happen was linked to Affirmative look at past fieldwork (0.67) and Recording and analyzing by trial and error (0.57). Furthermore, Recording and analyzing by trial and error was linked to Persistence and stepping ahead (0.67). The second subgraph contained not as expected, which was linked to Enjoying interactions with and receiving support from local people (0.75) and negotiation (with assistants and/or informants) (0.62). Not as expected was associated with responding flexibly (0.62), and Responding flexibly was further associated with Being well prepared (0.50). In the third subgraph, Impatience and frustration due to a feeling of uncertainty was included and linked to Enduring and enjoying spare time (0.50) and appropriate distance and relationship with colleagues and research associates (0.50). In addition, the study confirmed that enduring and enjoying spare time was associated with never giving in (0.50).

The fourth subgraph reveals a strong link between Crossing boundaries and unique feelings and behaviors while in the field (1.0), which was linked to knowing me (0.6). Moreover, knowing me was associated with Joy of encountering unanticipated things (0.6). The fifth subgraph includes becoming familiar with and accepting the local people and lifestyle, which had the highest number of occurrences and linked too haphazardly (0.62) and Comfort with a regularly scheduled life (0.62). In addition, Comfort with a regularly scheduled life was associated with never do anything reckless (0.60). Finally, the sixth subgraph contained three categories; with never overreach being associated with Sense of getting by (0.67) and Keeping a steady record (0.57).

Discussion

In the fields of humanities and social sciences, various types of resources and other data are used in research. The styles of the research vary from those in which the researcher develops a hypothesis based on the existing studies and systematically collects the data necessary for verification with those in which the researcher aims to discover a novel issue or generate a hypothesis, because few researchers are engaged in them. Many of the fieldwork studies examined in this paper are relatively similar to the latter style, and, in fact, require visiting the field, actually observing or interacting with the subjects or target individuals, and establishing a relationship with them before determining which data to consider and the method to be used for collecting them. In the case of research on wild animals or on the habits, rituals, and cultures of peoples for which information is unavailable, collecting data as planned may not always is possible. In certain cases, substantially and drastically altering the topic may be necessary. Furthermore, for long-term fieldwork, returning to the home country with a satisfactory research output is frequently imperative due to the high cost of staying and other expenses despite the highly unpredictable circumstances. The current study aimed to clarify their experiences in fieldwork, their motivation to pursue their research, and the lessons brought by their fieldwork experience. Toward this end, the study conducted interviews with mid-career researchers engaged in long-term fieldwork overseas for many years as they faced many of these challenges.

Experience of researchers undertaking long-term fieldwork overseas

A qualitative examination of the interviews identified six major categories.

Concerns, coping, and interpersonal relationships specific to field research: Unsurprisingly, fieldworkers go into the field for the purpose of research. Therefore, the most frequently mentioned narratives were related to research activities. First, a number of interviewees remarked on the fact that several plans deviate from their original expectations. Interestingly, the most representative responses were to let things happen as they go, not to overreach, and to be flexible and adaptable to whatever happens. Apparently, the willingness to accept the fact that things do not go as planned are seemingly natural, and remaining calm is one of the most basic attitudes required to continue fieldwork. Nevertheless, their narratives also suggested that fieldworkers need to be persistent and unyielding at critical moments, and, occasionally, they need to utilize their own characteristics tactfully and with a voracious appetite. Possessing a que sera attitude (letting things go as they come), perseverance, and strength to push forward vigorously was considered necessary for fieldworkers as well as skillfully striking a balance the two. Another interesting but related characteristic is the attitude of being well prepared. The narratives suggested that letting go with the flow is never done thoughtlessly and that constant preparation and skill development in pursuing research are necessary to improve sense of balance and the timing between the gas pedal and the brake. One intriguing remark made by an anthropologist was being reckless with a calm mindset. Unexpected situations normally occur in the field; thus, being prepared is considered effective as a foundation for coping with situations with a calm attitude.

In addition, the study obtained comments about impatience with the lack of prospects for research and pressure to achieve results, as was expected. As we have repeatedly indicated, long-term fieldwork requires a reasonable amount of funding, such that the researcher is expected to return to his/her home country with certain satisfactory achievements despite the little prospect of success. For example, in the study on wild animals and the ecological research on living creatures, daily observation and recording are extremely simple tasks. However, continuing to do so in a straightforward manner is, in fact, necessary. Although one cannot confirm visible results on a daily basis, one will only realize achievements with the accumulation of data. Thus, continued perseverance in such a work is also a unique trait of fieldworkers.

At the same time, however, such efforts do not always lead to good results, even if continued. Typically, one would have given up at a certain point, but the narratives of many participants revealed that those who could continue fieldwork would not be discouraged. Instead, they present an optimistic attitude that they could manage and that they would have the grace to change their research theme and, oftentimes, even switch the subject of the research. In fact, one biologist mentioned that she had been studying a certain animal for a relatively long time, but when she realized that it did not lead to any certain outcome, she switched to an entirely different set of data during her stay. Another participant (an anthropologist) talked about the fact that once he had got stuck collecting data at one research field, he dashingly and without remorse decided to explore another research field. The ease with which the fieldworkers were able to move from one theme or subject to another without hesitation was also considered to be a characteristic of fieldworkers.

Life in the field and relationships with the local people: Once again, a common discourse among many of the participants was that being able to familiarize themselves naturally with the lifestyles, customs, and practices of the local people and to do so effortlessly was important for continued fieldwork. One anthropologist referred to it as “being able to be there spontaneously.” Another anthropologist stated that they “definitely attend events to when invited” and “eat the food that is served to them.” Although anyone who has entered an environment that is relatively different from that in which he or she was born and raised can be imagined to experience a certain degree of culture shock, the acceptance of such shock without resistance and the ability to adapt to local customs and lifestyles easily are also considered necessary qualities for continuing fieldwork. As previously mentioned, unexpected things can happen in the field, and one may get into trouble that was previously never experienced. However, many of the participants pointed out that by becoming familiar with the local lifestyle, building relationships with the local people, and simply having fun, one will be able to get help when needed.

Temporary crossing between the real world and some other world: Many participants discussed the fact that the research field was overwhelmingly different from their everyday lives regardless of area of expertise. Moreover, they suggested that staying in the field for at least several months, instead of only a week or two, then returning, would give fieldworkers a unique perspective. The remark that intentionally going all the way to a world that is entirely different from one’s daily life is part of the distinctive characteristics of fieldwork is relatively common among anthropologists. One anthropologist described it as, “like going through a tunnel to another world.” However, the narratives of the participants also acknowledged that they had a sense of assurance that they would not go away and never come back, but only for a limited period of time. As will be discussed later, these border-crossing experiences were recognized as opportunities for seeing and touching objects that are normally unavailable, to possess feelings that can otherwise only be experienced in the field, and to view oneself and one’s country objectively, which were the driving forces that underlie the continued fieldwork.

Real pleasure/motivation of fieldwork: In everyday world, people are not frequently exposed to fresh or stimulating perspectives, as each day relatively repeats itself. In contrast, the participants discussed how going out into the field gave them opportunities to experience firsthand the feeling of being alive, to be freshly surprised by unexpected events, and to interact with people with whom they would not normally have contact. Consistent with previous statements, the fieldworkers who participated in this study generally shared a similar disposition of being comfortable with and enjoying things that differ from themselves and their environment. Through their fieldwork experience, they realized that the world is full of diversity, and these experiences led them to know themselves and to have an opportunity to view their own countries in an objective and calm manner, which they considered to be the most exciting aspect of fieldwork.

Personal change through fieldwork: The fieldwork experiences made all participants aware of a certain form of change. One of the things abovementioned aspects was exposure to the diversity of people and the environment, which was a great experience and led to an objective point of view on things. Another major experience was the tolerance for when their plans are not going as expected or taken for granted, an attitude of acceptance, calmness, and unfazed that their plans would turn out the way as they expected. Scholars reported that university training programs bring about self-growth and selfawareness through overseas residency experiences. However, the current study demonstrated the specifics of such experiences in a more concrete way.

Suitability for fieldwork: Regarding the question of whether or not anyone is suited for fieldwork, all participants responded that more or less so. They all shared a curiosity for novelty, a tolerance for things not working out as planned, and an ease in socializing with others. One participant noted that “fieldworkers, regardless of discipline, seem to have something in common,” and another stated that those who withdraw from fieldwork do not possess a few of these qualities.

Co-occurrence network analysis: Co-occurrence network analysis is a statistical method that is frequently used in text mining, which visualizes and shows the frequency and co-occurrence patterns of words with interview data as the main source. This process enabled six major cohesions to be recognized in this study. First, it included a strong motivation and curiosity for the unknown, a world that could never be experienced or seen in everyday life, and willingness to easily shift to new fields and themes. The motivation to see a different world was also associated with an attitude for letting things happen, which suggests that this attitude could lead to unexpected new discoveries and experiences that could not be obtained through a predetermined plan. In addition, the attitude of letting things happen was related to the positive perception of the fieldwork experience in their early years. This result indicates that the initial experience may have played an important role. A few of the biologists and anthropologists among the participants described their strong impression that the first fieldwork was just a lot of fun.

The second cohesion centered on things not proceeding as planned, which many of the participants mentioned from their specific experiences. At the same time, however, this unpredictability was strongly associated with support from the local people and with negotiations with assistants and informants who were indispensable to the research activities. For example, zoologists are frequently required to travel long distances through forests, because the location of a target animal for that day is frequently unknown. In these situations, an assistant who is familiar with the local geography is essential. One of the participants talked about an experience in which a hired assistant repeatedly failed to appear at the appointed time. However, she persistently negotiated and maintained the relationship; thus, she was able to successfully collect valuable data. In addition, not having things go as expected was associated with flexibly responding to situations. Interestingly, this flexible response was related to being well prepared, which suggests that careful preparation enabled a flexible response to unexpected situations.

The third cohesion included impatience and frustration regarding the uncertainty of research prospects. In fieldwork, uncertainty about research prospects is common and repeatedly encountered, and the traditional scientific research method, which aims to formulate a hypothesis in advance and examine it, rarely succeeds. In general, the basic principle of fieldwork is to start a research by first going to the actual site and generating research questions [2]. However, research themes are not always found immediately, and finding the appropriate theme often takes time. Moreover, even after a theme is established, immediately getting in touch with the target of the observation or the person with whom one wants to talk may not always be possible, such that one may be stuck in a place for days or even months. One zoologist described his anxiety after a month in the forest, when he could not see a target for observation and only had to patiently wait for it to appear. This scenario suggested that tolerance of such situations it is necessary for long-term fieldworkers; in certain cases, they need to be patient to enjoy the situation.

The fourth cohesion included the word boundary crossing. Many of the participants expressed the nuance that going into a field involved willingness to go to a place that is tremendously far removed from the everyday world. In a highly emphatic tone, one anthropologist mentioned that taking the time and effort to access a site by taking the bus and spending hours on unpaved roads instead of flying was essential for him to change his mind into a mode that differed from his daily activities, and that it was like a ceremony for him. Another biologist noted that as soon as they pass through the departure gate at the airport, he feels prepared for no turning back, and his feelings are calmed. The peculiar sensations that can only be experienced in the field and the behavior in the field were deeply connected with such transboundary experiences and with the objective reconsideration of oneself. The narratives implied that long-term overseas fieldwork provides a fascination that captivates those who have experienced the real excitement of fieldwork.

In relation to the fifth cohesion, the participants said that once they were in the field, they were able to easily adapt to the local lifestyle and the style of interacting with people, which was common to many of the participants. Within this cohesion, this attitude was further linked to conducting research in a haphazard manner, which indicates the need for a spontaneous attitude instead of going against the local way of doing things in the field.

Finally, the sixth cohesion consisted of an attitude of never overdoing things in research, collecting and recording data diligently, and maintaining an optimistic attitude that things will be all right. To stay in the field for a long period of time and carry out the research continuously, collecting data continuously without disruption of concentration is necessary. The study infers that to maintain this concentration, possessing an optimistic attitude that if they kept at it, they would get by may be imperative.

Conclusions

The interviews were conducted with researchers engaged in longterm fieldwork overseas across disciplines. Beginning with episodes from their earliest days in the field, the researchers were interviewed about how they felt when they went out into the field, what it was like in the field, what troubles they experienced thus far, and what they learned or changed as they continued their fieldwork. The text data were classified and analyzed for co-occurrence and relevance in the content of their utterances. Analysis revealed that fieldworkers, regardless of their discipline, have a unique research style and attitude deeply related to the fact that they have to conduct their research activities based on the assumption that things do not go on as planned, a curiosity for sensations, and new stimuli that can only be experienced by crossing over into a world that is overwhelmingly different from everyday life. A flexible mindset enables them to acknowledge and enjoy that the world is comprised of a diverse range of landscapes. The results also indicated that years of fieldwork experience may influence the values and attitudes of an individual, as well as the nature of one’s interpersonal relationships.

One of the limitations of this study is that the research fields of the interviewees were limited to a certain extent. A few areas of study in which fieldwork is conducted, such as archaeology, geology, and geography, address nonliving subjects, while others typically require a group of many people to go into the field to investigate. Thus, whether or not these people have the same experiences as those in the current study remains to be examined. In addition, whether or not they have entirely different narratives requires further clarification. Furthermore, whether or not individuals who were able to continue fieldwork possessed qualities that enabled them to do so, whether or not they acquired qualities suitable for fieldwork as they continued their activities, or whether or not they were interacting with one another was unclear based on the data in this study. To determine these aspects, conducting a longitudinal study is necessary. Future studies are also necessary to find out this.

References

- Malinowski B (2001) Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. 1st edn, London: Routledge & Sons.

- Bernard HR (2017) Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 6th edn, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dewalt KM, Dewalt BR (2010) Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. 2nd edn, Maryland: AltaMira Press.

- Ybema S, Yanow D, Wels H, Kamsteeg FH (2009) Organizational ethnography: Studying the complexity of everyday life. 1st edn, London: Sage.

- Kanas N, Weiss DS, Marmar CR (1996) Crewmember interactions during a mir space station stimulation. Aviat Space Environ Med 67: 969-975.

- Pierson DL, Stowe RP, Phillips TM, Lugg DJ, Mehta SK (2005) Epstein-barr virus shedding by astronauts during space flight. Brain Behav Immun 19: 235-242.

- Stowe RP, Pierson DL, Barrett AD (2001) Elevated stress hormone levels relate to epstein-barr virus reactivation in astronauts. Psychosom Med 63: 891-895.

- Zimmer M, Cabral JCCR, Borges FC, Coco KG, Hameister BDAR (2013) Psychological changes arising from an antarctic stay: Systematic overview. Estudos de Psicologia 30: 415-423.

- Hummel AC, Kiel EJ, Zvirblyte S (2016) Bidirectional effects of positive affect, warmth, and interactions between mothers with and without symptoms of depression and their toddlers. J Child Fam Stud 25: 781-789 .

- John CM, Khan SB (2018) Mental health in the field. Nat Geosci 11: 618-620.

- Phillips T, Gilchrist R, Hewitt I, Scouiller S, Booy D, et al. (2007) Inclusive, accessible, archaeology: Good practice guidelines for including disabled students and self-evaluation in archaeological fieldwork training. 1st edn, The Higher Education Funding Council for England.

- Konno H (2022) Field kyouiku to gakushu seika. Hito to Kyouiku 16: 8-12.

- Kobari Y (2021) Analysis of participant reports for the overseas experiential learning program: Multicultural field study in the Philippines. J Int Relat Asia Univ 30: 179-200.

- Wakabayshi M, Ieshima A, Uwasu M, Si Q (2019) Impact of the short-term overseas field study program on career development: Follow-up study of graduate students. Osaka University Higher Education Studies 7: 23-30.

[Crossref]

- Yakushiji H (2017) The performance amongst Japanese-participated orphanage volunteer tour in Cambodia. Tour Rev 5(2): 197-213.

[Crossref]

- Yabuta H (2020) Effects of fieldworks on university students' learning and adaptation to campus life. Bulletin of Mimasaka University Mimasaka Junior College 53: 43-52.

- Ohira W (2021) Lasting impact of international service learning: A case study of a service learning program in Africa. J F Oberlin Journal of Service Learning 2: 28-40.

- Moriizumi S (2021) Significance and tasks of overseas fieldwork: Through the implementation of GLS fieldwork (Philippines). J Nanzan Academic Soc 21: 155-167.

- Kawakita J (1975) The KJ method: A scientific approach to problem solving. Tokyo: Kawakita Research Institute.

- Scupin R (1997) The KJ method: A technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology. Hum Organ 56(2): 233-237.

- Higuchi K (2014) Quantitative text analysis for social researchers: A contribution to content analysis. Nakanishiya 1-16.

- Higuchi K (2016) A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using anne of green gables (Part I). Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Rev 52 (3): 77-91.

- Cioban S, Lazar AR, Bacter C, Hatos A (2021) Adolescent deviance and cyberdeviance: A systematic literature review. Front Psychol 12: 748006.

- Wiley SMP, Terada M, Kinoshita I (2018) The psychological ownership of ethnobotanicals through education. Environ Behav 3(8): 12-21.

- Sakurai R, Stedman RC, Tsunoda H, Enari H, Uehara T (2022) Comparison of perceptions regarding the reintroduction of river otters and oriental storks in Japan. Cogent Soc Sci 8(1): 2115656.

- Yamashita A, Nakajima T (2022) Nursing students’ use of recovery stories of people with mental illness in their experiences: A qualitative study. Nurs Rep 12(3): 610-619.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi