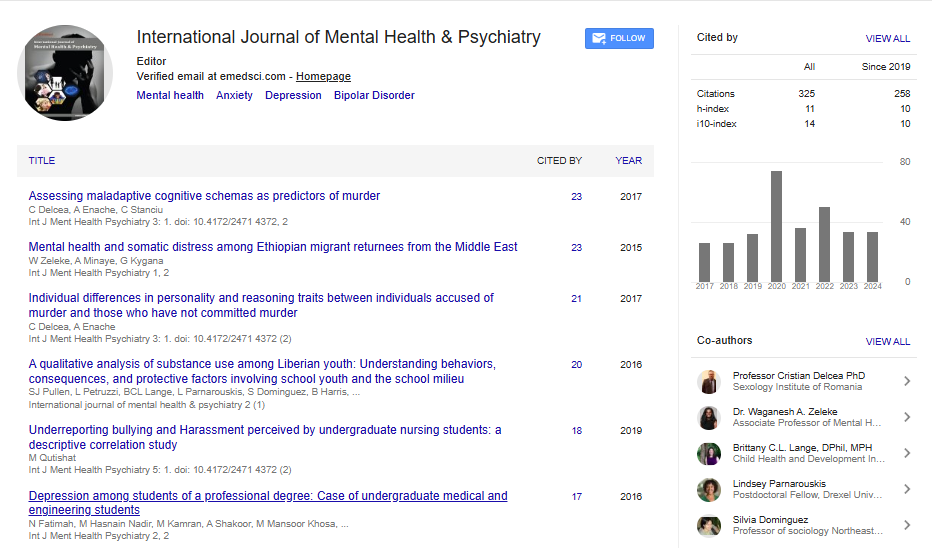

Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 4 Issue: 2

Asian American Mental Health Care: With a Special Focus On the Chinese Population

Xia Wang*

M.S., Mental Health Counselor, Wisconsin, USA

*Corresponding Author : Xia Wang

M.S., Mental Health Counselor, Wisconsin, USA

Tel: 608-433-5818

E-mail: xiawang080211@gmail.com

Received: June 2, 2018 Accepted: June 27, 2018 Published: July 4, 2018

Citation: Wang X (2018) Asian American Mental Health Care: With a Special Focus on the Chinese Population. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 4:2. doi: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000164

Abstract

The Chinese population has a high prevalence of mental illness, but the treatment gap is high; identifying the barriers to mental health services utilization can improve access and promote better mental health care. Very few empirical studies systematically examined the barriers to help-seeking in the Chinese population. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to review the literature on the utilization of mental health services by the Asian American population in order to understand the barriers in seeking professional mental health care among the Chinese. As part of this study, a mix method research survey comprising 10 demographic questions and 26 multidimensional questions pertaining to barriers for accessing mental health services was conducted. This survey combined open-ended and closed-ended questions. The results revealed that people of Chinese descent are less likely to use mental health services due to the critical influence of its culturally-oriented values and beliefs in perceptions of mental health issues and help-seeking behaviors. The practical implications include more culturally appropriate services, changing policy, and addressing stigma through interventions. Since it is a pilot study focus on preliminary data collection with a small sample to test out the survey questionnaire, so further studies with a larger sample population of Chinese especially in China should be carried out to better examine the barriers to mental health services by the former.

Keywords: Asian Americans; Chinese; Mental health services; Mental health treatment barriers; Underutilization of services

Introduction

Mental health disorders are a growing public health concern in China [1]. Zhou Dongfeng, the president of the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, noted that at least 100 million Chinese have various mental disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social phobias [2]. According to Wong et al. there were about 174 million adults in China with a mental disorder [3]. Moreover, Phillips et al. reported that an adjusted onemonth prevalence of any mental disorder in China was 17.5%; the prevalence of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance disorders, and psychotic disorders were 6.1%, 5.6%, 5.9%, and 1.0%, respectively [4]. Compared to the worldwide statistics of community-based epidemiology, the estimated rates of lifetime prevalence of mental disorders among adults ranged from 12.2 % to 48.6% and 12-month prevalence rates ranged from 8.4% to 29.1% [5].

According to China’s Ministry of Health, at least 250,000 people in China commit suicide per year; that is a rate of about 20%-30% per 10,000 compared to a worldwide average of 14% [6]. In urban areas, suicide is often committed by jumping from high-rise buildings or into rivers, and in rural areas; ingesting poison is the primary means of suicide [2]. Zhu Qingsheng, China’s Vice Health Minister addressed the concern that mental health problems have threatened the development of China’s human resources [6]. This tremendous burden of mental illness demonstrates the need for improved mental health services [7].

However, the rate of treatment gap-the percentage of individuals who require care but do not receive treatment-is unacceptably high in China [1]. About 91.3% of all individuals with any diagnosed mental disorder have never received any kind of professional help; in additional, only 8% have ever sought professional health care with regard to mental health and only 5% have ever seen a mental health professional [4,7]. This treatment gap must be addressed in order to reduce the mental health burden, which means exploring factors that influence the utilization of mental health treatment [1]. Leong and Lau noted that identifying the barriers to mental health service utilization can improve access and promote better mental health [8]. Nevertheless, it revealed that there are very few empirical studies examining these barriers within Chinese population when locating literature review. Therefore, the research terms were broadened to Asian Americans in order to gain empirical evidence to create a survey questionnaire to understand how Chinese response to the barriers.

The underutilization of mental health services for Asian Americans as an ethnic minority has been well documented [9]. The factors that influence Asian Americans’ use of mental health services include race and ethnicity, birthplace and acculturation, age, gender, marital status, education, financial status, language and attitude, beliefs, and practices toward mental health services [10-15]. In addition, social and structural stigma and discrimination, and the traditional Chinese belief system on mental health were also important barriers [16].

In order to prevent overgeneralizations and stereotyping, it was important to note that Asian Americans are a heterogeneous group with over 20 subgroups with their own culture, language, sociodemographic backgrounds, and immigration histories to the United States. Leong and Lau indicated that this diversity means differences in mental health service needs, utilization, and outcomes, but often Asian Americans are treated as a single category [8]. There are very few empirical studies of mental health services for each subgroup as the majority of studies tend to treat Asian Americans as a single category. Leong and Lau stated that it was important to study heterogeneity to improve the service delivery system [8]. More qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies should be conducted in order to better understand the problem of underutilization of mental health services by specific Asian ethnic groups. The purpose of this study was to review the literature on barriers to accessing mental health services by Asian American and, to examine how these barriers to service utilization vary within the Chinese population. The comprehensive survey presented as part of this study was used to evaluate the perceptions and attitudes toward mental health services use among Chinese. This is a pilot study involves preliminary data collection with a small sample, so more comprehensive research studies with a larger Chinese population will be needed in order to more adequately understand the underutilization of mental health services by the latter.

Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review examined the barriers to seeking mental health services for Asian Americans. This study started research on the databases of PsycARTICLES at Viterbo University library. The research terms were: Chinese populations, underutilization of mental health services, the barriers of seeking mental health care, which yielded about 375 articles. The researcher filtered the criteria of “full text, reference available, abstract available, publication datas from 2007 to 2017, peer-reviewed, and classification as cultural and ethnology,” and then it yielded 23 papers. The further inclusion criteria were primary sources with related to the barriers of seeking mental health care within Chinese. However, there was no result found. Then the researcher terms were broadened to Asian Americans and the barriers of underutilization mental health services. Eventually, ten primary sources regarding empirical evidence of barriers to seeking mental health services among Asian America were eligible for review. These ten studies were summarized in the literature review, which includes the content of the purpose of the study, methodology, relevant findings, limitations, and implications of the study.

According to previous investigations, there were three major barrier patterns to the utilization of mental services among Asian Americans, including cultural pattern, physical pattern, and demographic pattern. Regarding cultural pattern, it includes cognitive, affective and valueoriented barriers [8,9]. Cognitive barriers refer to personal beliefs and attitudes toward mental health services and self-perception of need. Affective barriers include responses to mental health problems, such as shame and stigma. Finally, value-based behaviors address the norms for mental health management, such as the traditional Asian belief system on mental health and general coping behaviors toward mental health. According to Leong and Lau, barriers can also be physical, practical, actual and structural [8]. In addition, demographic factors such as birthplace, acculturation, age, gender, and marital status also influence whether Asian Americans seek services. The literature review explored demographic barriers, cultural barriers, and physical barriers related to Asian Americans’ use of mental health services.

Demographic barriers to using mental health services

The use of mental health services and user satisfaction is very subjective and can be influenced by birthplace and generation. Abe- Kim et al. addressed the utilization rate of mental health-related services among immigrants and U.S.-born Asian Americans during a period of 12 months [10]. Various immigration-related characteristics (nativity status, years in the United States, English-language proficiency, age at the time of immigration, and generational status), and the perceptions of satisfaction with care and helpfulness on the basis of data from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) were examined. The sample (n=2095) of Asian Americans (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and other) were 18 years old or older and resided in any of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. All participants were interviewed by trained bilingual interviewers face-toface or on the telephone, and the NLAAS instruments were translated with standard translation and back-transition techniques into English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese. The findings indicated that only 8.6% of all Asian Americans sought help through any services [10]. Moreover, just 34.1% of all Asian Americans who had a probable DSM-IV diagnosis sought any services. U.S.-born individuals had significantly higher rates of using any services and seeking mental health care, but not of using general medical care when compared to individuals born outside the United States. In addition, third-generation or later participants with a DSM-IV diagnosis during the 12 months sought help from services at significantly higher rates (62.6%) than did first-generation (30.4%) or second-generation (28.8%) respondents. One limitation was that the cross-sectional survey was based on a retrospective report, so the findings were subjective and had inherent reporting biases. In addition, the validity of the measures was not thoroughly established across the different Asian American ethnic groups. Moreover, the study did not consider other factors that could affect patterns of service use, such as gender, regional variations, income and immigration-related factors. Finally, the study used “other Asians” as a single category which combined various Asian languages, ethnicities, cultures, and practices. Despite these limitations, Abe-Kim et al. suggested that future research could explore how birthplace and generation affect patterns of service use and perceived helpfulness of care [10]. This study was valuable as it helped identify a need to destigmatize utilization of services for Asians.

The second study indicated that age, length of time living in the United States, and culture-influenced personal beliefs were the main determinants of the utilization of mental health services. Jang et al. studied the determinants of attitudes toward mental health services in older Korean Americans (aged ≥ 60) among three different category variables: predisposing factors (age, sex, marital status, length of residence in the United States), mental health needs (anxiety, suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms), and enabling factors (personal experiences and beliefs [11]. An abbreviated version of the Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale was conducted in Korean among 472 participants. The researchers found that the older population showed high rates of mental health problems and an underutilization of mental health services. In addition, individuals who had lived in the United States longer were more likely to have favorable perceptions of the utilization of mental health services. The study also suggested that culture-influenced personal beliefs, like knowledge about mental illness and stigmatism, played a critical role in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward mental health services.

The study called attention to assess how culture influenced the response to mental health needs, establish community education, and outreach programs to close the gaps between mental health needs and service utilization in the older ethnic minority population. A limitation was the cross-sectional design. In addition, the sample was nonrepresentative and cognitive abilities were not systematically assessed. Furthermore, assessment of predictive variables was limited to the population’s barriers, so future research could explore a broader spectrum of barriers, such as environmental and system-level variables. Moreover, the research could extend to the assessment of access and quality issues in mental health services among minority populations [11].

Cultural barriers to using mental health services

Cognitive barriers: Culturally informed conceptions of mental illness shared by Asian American were one type of barrier in seeking mental health services [8]. The following two studies revealed how these ideas of mental health and mental health treatment influenced the utilization of mental health services. The first study indicated that stigmatizing beliefs about mental disorders and mental health treatment deeply influenced Asian Americans’ use of mental health services compared to other ethnicities. Jimenez et al. identified the differences in stigmatizing beliefs about mental disorders and mental health treatment among Whites, African-Americans, Asian- Americans, and Latinos; the study focused on common mental health problems including depression, anxiety disorders, and alcohol abuse [12]. The study used baseline data collected from participants who finished the Mental Health and Alcohol Abuse Stigma Assessment measure. Then they developed for the Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for the Elderly (Prism-E), which was a multisite randomized trial for all participants aged 65 years and older who initially seen by or referred to the study by their primary care clinician. The final study sample consisted of 2,244 participants, including 1,247 Whites, 536 African-Americans, 112 Asian- Americans, and 303 Latinos.

The results of the study suggested that there were differences in stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness and mental health treatment among older adults of various races/ethnicities with a mental disorder. Asian-Americans expressed greater shame and embarrassment of having a mental illness and greater difficulty in seeking mental health treatment than members of the other races and ethnicities. Limitations were associated with the sample, study methods, and design. First, the participants were older primary care patients with a diagnosis of depression, anxiety disorder, or at-risk alcohol use, so the results may not apply to other older adults with other mental health disorders. Second, participants were randomized with two different models of mental health treatment, so perceived stigma related to engaging in mental health treatment may differ. Third, both Latinos and Asian-Americans are people of different nationalities with different cultures, but in the study, they were treated as homogeneous groups. Finally, the stigma assessment measure had no psychometric information. Although these results need to be viewed with caution, they can help researchers and clinicians provide culturally specific psychoeducational materials and implement culturally appropriate interventions when engaging with older adults in treatment for mental health disorders. In addition, Jimenez et al. suggested that future research examine to what extent acculturation level mediates stigmatizing beliefs [12].

Second, individuals’ perceptions of their mental health need to affect their attitudes about seeking help. Nguyen and Bornheimer et al, examined how sociocultural and need factors influenced the patterns of mental health service use by Asian American with a psychiatric disorder [17]. The study sample (n=230) was obtained from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) through multistage random sampling and second-responding; the sample was 32.61% Chinese, 25.22% Filipino, 20% Vietnamese, and 22.17% other Asian. The dependent variable of types of mental health services used in the past 12 months was measured in four categories: mental health specialists, general medical, both mental health specialist and general medical, and no use. The independent variable of the severity of need was measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale, and the perception of mental health need was assessed by asking if participants had a nervous, emotional, drug or alcohol problem anytime in the past year. In addition, acculturation level was reported by the indicators of generation status and English proficiency. The results indicated that about half of Asian Americans with severe mental health needs sought mental health services, a rate higher than the general population. Furthermore, those Asian Americans with severe mental health needs often received services from a mental health specialist or through both mental health services and general medical care. Even though Asian Americans had severe levels of need, social and systemic barriers often prevented early identification and intervention for mental health disorders. In addition, results showed that perception of need played a significant role in service use patterns. Those who conceptualized problems as mental-health-related were more likely to seek care from mental health specialists alone or combined with a general medical provider. Limitations consisted of underrepresented sample size and cross-sectional data. This study might be useful in improving individual health care and potentially reducing health care costs, improving outcomes and satisfaction. Nguyen and Bornheimer suggested that future research examine multidimensional models in mental health help-seeking, such as social policies, organizational factors, and individual-level decisions [17].

Affective barriers: Even after the diagnosis of a mental disorder, culturally based affective responses may act as another source of barriers for Asian Americans in seeking professional help [8]. The following study demonstrated that perceived stigma of mental illness played a critical role in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward service use. Park et al. addressed the differential influences of various factors associated with the utilization of mental health services [13]. Specifically, the researchers explored a correlation between perceived stigma of mental illness and the utilization of mental health services across various age cohorts. The sample (n=3,055) were Koreans age 18 to 74, and the subjects were classified into three age groups: young (18-39), middle-aged (40-59), and late adulthood (60-74). The degree of stigmatization of mental disorders was assessed using the Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination (PDD) scale. The influence of perceived stigma on lifetime utilization of mental health services was examined by logistic regression analyses per age cohorts, which adjusted for demographic variables.

The results of the study revealed that those who had a low level of stigmatization of mental disorders used mental health services more than twice as often as those who expressed a high level of stigmatization. In addition, the elderly cohort group was more likely to have a stigma associated with mental illness than the young cohorts. Moreover, the results revealed that females and never married middleage adults were more likely to use mental health services. One limitation was the cross-sectional investigation based on retrospective reports, so the results may not reflect the actual time of utilization of services by the subjects. In addition, the sample only included community-dwelling individuals, so could have excluded those who had already used mental health services. Park et al. suggested the need for longitudinal analyses to identify additional demographic factors and associations with lifetime use of services [13]. The study indicated that decreasing the stigmatization of mental health was a way to improve the utilization of mental health services among elderly Koreans.

Value orientation barriers: Another type of barrier in seeking professional help involved cultural values that govern norms for mental health treatment. Traditional Asian American hold collectivistic values, which are opposed to the values related to Western psychotherapy. Individuals with roots in Asian cultures often prefer to keep personal and family problems in confidence within the kinship domain since the shameful belief of disclosure these problems to others [8]. The following study revealed that Asian Americans did not indicate a preference for seeking counselors as a source of help. Yeh et al. investigated Asian American coping in terms of attitudes, sources, and practices when dealing with mental health concerns. The sample of participants consisted of 470 Asian American undergraduate and graduate students from nine universities and colleges from the east and west coasts, including 240 Chinese Americans, 62 Indian Americans, 65 Filipino Americans, and 103 Korean Americans. All the participants were asked to complete a Demographic Questionnaire and a Coping Attitudes, Sources, and Practices Questionnaire [15].

Overall, participants showed negative attitudes towards professional counseling, tended not to share problems with a counselor because they felt uncomfortable, and did not believe a counselor could provide assistance. Instead, they preferred to keep problems within the boundaries of the family, sharing problems with parents, siblings, friends, boyfriends or girlfriends, or keeping problems to themselves. Moreover, females were found to be significantly more likely to have positive attitudes about seeking professional counseling but there were no ethnic differences with regard to coping attitudes. The researchers also found that Korean American students were significantly more likely to cope with a mental health problem by talking to a religious leader or engaging in religious activities. One limitation was the demographics of the sample, so the results may not be generalizable. Despite these limitations, the data provided valuable information about coping attitudes, resources, and practices among Asian Americans and assessed why Asian Americans underused mental health services. Future research could include the comparisons across diverse racial and socioeconomic groups in terms of cultural values and indigenous coping [15].

Physical Barriers to Using Mental Health Services

The physical barriers were regarding practical barriers to actual use and structural barriers, such as people lacking awareness of available services or access to services due to economic and geographic realities [8]. The following four studies demonstrated the specific physical barriers to seeking mental health services. First, Cheng et al. examined social and structural stigma experienced by Chinese immigrant patients with psychosis [16]. The sample (n=50) was recruited from two Chinese bilingual psychiatric inpatient units in New York City, and the diagnoses were based on DSM-IV-TR. The study was a semistructured interview based on grounded theory, which examined participant experiences of stigma using an adapted version of the Experience of Stigma Questionnaire and interviews in either English or Mandarin Chinese. The results detailed the top five experiences of social and structural stigma. The most prevalent form of social stigma experienced by participants was being shunned or avoided by others (44%); similarly, 42% of the consumers reported that family members looked down on them because of mental illness. More than 36% of the consumers reported being treated as less competent, 30% had difficulties finding a romantic partner, and 30% were told by family members to hide their mental illness. The top forms of structural stigma were a lack of financial resources (16%), a language barrier (16%), or a lack of insurance (10%). Furthermore, structural stigma from law enforcement officers (16%) and health professionals (12%) was reported [16]. Social stigma was far more prevalent than all other forms of stigma and was the main barrier that impeded Chinese immigrants from seeking mental health treatment. Limitations included a small sample and convenience sampling. In addition, selfselection could have resulted in participants have least stigmatized. There also could have been biases from the coders: two authors are Chinese immigrants with legal status and higher educational status, which could have caused undocumented individuals to feel subtle structural forms of discrimination. Despite these limitations, the study was relevant with regard to policy changes and anti-stigma interventions. Future research could focus on clarifying the family role in the stigma experienced by Chinese immigrants with psychosis [16].

Second, Spencer et al. studied the relationship between perceived discrimination and the utilization of formal and informal mental health services among a national sample of Asian Americans [14]. The data was collected from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), the first national study of Asian Americans. The national sample of Asian Americans included 600 Chinese, 508 Filipinos, 520 Vietnamese, and 467 other Asians (n=2,095). Participants were interviewed in English or their mother language to assess the association between discrimination and services use as well as the interaction between discrimination and English proficiency. The data indicated that perceived discrimination was associated with greater use of informal mental health services, but was not associated with the less frequent use of formal services. Moreover, the data showed higher levels of perceived discrimination with lower English proficiency associated with more use of informal services. The study also suggested a correlation between a lack of health insurance and greater use of informal services. Limitations included limited diversity among participants, no standardized measure to assess language-based discrimination and self-reported data. Spencer et al. suggested that future research focus on the factors that draw Asian Americans to formal services even though they may face discrimination and/or lack English proficiency [14]. The study proved that discrimination was a critical factor in the utilization of mental health services among Asian Americans, which is beneficial in advocating for more bilingual and culturally appropriate services.

Third, Kung examined the relationship between barriers to using mental health services and the predictive power of actual service use based on a larger and more representative sample (n=1,747). The sample data was collected based on a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) funded strata-cluster survey for participants between the ages of 18 and 65. The participants were asked to measure items in the areas of perceived barriers to mental treatment, help-seeking, acculturation, and mental health conditions. The interview was administered by bilingual interviewers and took about 90 min. The results indicated that the greatest barrier was the cost of treatment, with a mean of 3.12 (SD=.98), followed by language, time, knowledge of access, and recognition of need. The lowest rated barriers were the credibility of treatment and a fear of losing face [9]. All of the items were correlated at the level of p ≤ 0.001; expect the language with the credibility of treatment and with loss of face. Overall, the perceived practical barriers had a significant predictive power of mental health service use. A limitation of the study was the low levels of reliability of the measuring scale, so Kung suggested that future research could further refine the measurement constructs to increase psychometric properties. The study was useful because it provided a guideline to address these issues in order to increase the utilization of mental health services among Chinese American population.

The last study revealed how structural barriers reciprocally interact with cultural barriers that influence the utilization of mental health services. Yang et al. integrated frameworks of “structural vulnerability” and “moral experience” to investigate how structural discrimination reciprocally interacted with cultural engagements to produce stigma and mental health disparities [18]. Fifty Chinese immigrants were recruited from two Chinese bilingual psychiatric inpatients units in New York City from 2006 to 2010 to discuss stigma experiences of mental illness. Interviews were conducted predominantly in Mandarin Chinese by one of the Chinese psychologists and the questions were derived from four stigma measures of various life domains. The mixedmethods study used quantitative and qualitative approaches. The participants were asked to elaborate on their open-ended narrative data based on initial rating response to measure items, and the narrative data was analyzed by a deductive approach [18].

The results revealed that mental illness stigma was related to the degree to which immigrants were able to work to achieve “what mattered most” in their cultural context. Structural vulnerability made it harder for new immigrants to access to affordable mental health services [18]. For instance, structural discrimination (institutional policies that intentionally or unintentionally limit the rights of people with mental illness) increased the participants’ treatment costs and interfered their financial accumulation leading to non-adherence to treatment and mental health disparities. Furthermore, participants indicated an internalized powerless structural vulnerability position and extended this view to their experience in the healthcare system, which led to a depreciated sense of self and a reduced capacity to advocate for healthcare system changes. Limitations were the small sample size; convenience sampling that could have caused biases, and potentially underestimating the extent of stigma. In addition, the data only represented the views of Chinese immigrants with mental illness, so the study could be augmented to include other Chinese immigrants. Furthermore, the study focused on structural discrimination, so it possibly overlooked other aspects of discrimination. Despite these limitations, the study emphasized for mental health providers to use the “what matters most” approach to combat stigma for Chinese immigrants facing structural vulnerability. Yang et al. suggested that future research could focus on how local cultural processes and structural mechanisms contribute to stigma experiences and health in other cultural groups.

Rationale

China has been experiencing rapid economic development and changes in lifestyles and culture such as stressful work environments, tense interpersonal relationships, and fast-paced lifestyles, which has resulted in greater mental health problems [19]. The huge treatment gap between mental health need and mental health treatment is a critical issue in the current Chinese mental health system [1,7]. Recognizing the factors that influence the utilization of mental health treatment and identifying the barriers to mental health service utilization are critical steps in reducing the mental health burden [1,8]. A review of the literature revealed that multidimensional barriers in seeking mental health services were well documented among Asian Americans, but relatively few empirical studies examining these barriers among specific Asian ethnic groups such as the Chinese exist. Therefore, the underutilization of mental health services within the Chinese population requires further study. In this study, the literature on the literature of mental health services by the Asian American population was reviewed in order to understand the barriers to seeking professional mental health care among the Chinese. The overall objective of the study was to develop a comprehensive survey based on the literature review to evaluate the perceptions and attitudes toward mental health services use among the Chinese.

Methodology

The research question was: What factors restrict the access to and use of mental health services within the Chinese population? The hypothesis was that there were specific barriers for access to mental health services within this population. This mixed method survey research study was designed to gain an understanding of how socially shared mental health barriers impact the utilization of mental health services within the Chinese population. This non-experimental survey research was granted by school institutional reviewer board (IRB) committee before recruited participant in order to protect the rights and welfare of humans participating as subjects in the research study. Participants in this pilot study completed the demographic questionnaire and the multidimensional barriers questionnaire, which featured a combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions. The formats of the questionnaire were primarily Likert-type scales and multiple-choice questions. Emailed surveys were the main method of data-collection. Surveys were selected as they can generate useful perception-based data and are inexpensive [20].

To be eligible for the study, participants had to be Chinese by birth or of bilateral Chinese descent, have an eighth-grade level of English, and be 18 years old or older. Due to time constraints, this study relied on convenience sampling and a snowball referral technique. The participants were recruited from both USA and China between the dates 9/28/2017 and 10/23/2017. The survey questionnaires were created based on findings from the review of research literature and consisted of 10 demographic questions and 26 survey questions; surveys took approximately 10 min to complete. The main challenge in conducting the survey research was to get individuals to buy into the research and complete the questionnaires. To motivate potential respondents to complete the survey, a cover letter and informed consent form were included. The cover letter provided identifying information about the researcher, the purpose of the survey, potential benefits and disadvantages to participation, and the importance of the participant’s cooperation. The informed consent form included identification and qualifications of the researcher, the purpose of the study, how the research was to be conducted and if there could be any possible risks, discomforts, or benefits [20]. This data was analyzed for distribution and central tendency within descriptive statistics, and it was organized in Excel. Since this action research is for exploratory purpose and the limited generalizability of the findings and recommendations will be shared in the discussion section. There were several ethical issues the researcher paid attention to when conducting this research: G.1.b. Confidentiality in research, G.1.e. Precautions to avoid injury,G.2.a. Informed consent in research, G.2.d. Confidentiality of information, G.3.a. Extending researcher-participant boundaries, and G.4.a. Accurate results [21].

Results

There were 54 participants (22.22% male, 77.78% female). Of the participants, 64.81% lived in the United States for an average of 12 years, and 35.19 % were residing in China. Among the sample, 47.27 were working, 49.12% were non-religious, 42.59% were married, and 38.89% had a graduate degree. Detailed descriptive statistics regarding the participants’ demographic information are shown in Table 1.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender Male Female |

N=54 12 (22.22%) 42 (77.78%) |

| Age 21-29 30-39 65 and older |

N=54 19 (35.19%) 15 (27.78%) 1 (5.56%) |

| Marital status Single, not married Married |

N=54 22 (40.74%) 23 (42.59%) |

| Education Bachelor’s degree Graduate degree |

N=54 16 (29.63%) 21 (38.89%) |

| Live in the U.S. Yes No |

N=54 35 (64.81%) 19 (35.19%) |

| Years living in the U.S (Mean) |

N=35 (12.17) |

| The place got the highest education USA China Other |

N=55 29 (52.73%) 20 (36.36%) 6 (10.91%) |

| Citizenship USA China |

N=55 14 (25.45%) 37 (67.27%) |

| Employment status Working Not working Student |

N=55 26 (47.27%) 10 (18.18%) 15 (27.27%) |

| Religious affiliation and/or practice Christian Non-religious Buddhist Muslim Catholic |

N=57 23 (40.35%) 28 (49.12%) 2 (3.51%) 1 (1.75%) 1 (1.75%) |

Table 1: Characteristics of Participants’ Demographics.

Among all respondents, in the previous 12 months, 78.57% indicated no use of any mental health services from professionals, 5.36% sought mental health help from mental health specialists, 12.50% sought mental health help from general medical providers, and 3.57% sought help from any professionals. No participants answered the open-ended question concerning the reasons that might motivate them to seek professional help for mental health problems. Thirty-two participants answered the open-ended question regarding the reasons that might stop them from seeking professional help. The reasons included: “I do not think I need help for mental health” (40.63%), “I do not think I have a mental health problem” (25.0%), “I prefer to talk to family members and friends” (6.25% ), “I am worried about other’s judgment” (6.25%), “I have a lack of time” (3.13%), “insurance doesn’t cover enough” (3.13%), “hard to approach the appropriate services” (3.13%), “I feel shame to talk about some mental issues” (3.13%), “professionals do not help” (3.13%), and “there is a language barrier” (3.13%).

Participant answers to the Multidimensional Barriers Questionnaire are reported in Table 2, and the questionnaire items are listed from most to least frequent. Based on the rating percentage of “4” (the statement as “somewhat true”) and “5” (the statement as “very true”), as much as 55.32% of respondents considered mental health problems make it more difficult to find a spouse and romantic partner. Likewise, the majority considered talking to parents, friends, or religious leaders and keeping problems to themselves as their first inclination when dealing with mental health problems (54.17%). Over half of participants (53.19%) felt people were avoided when it was revealed that they had mental health problems; similarly, 53.19% believed that people with mental health problem were not well understood by law enforcement officers. Overall, based on the mean of the reasons for not seeking mental health services, social and structure stigma was the most frequent (42.86%), followed by value orientation (31.26%), cognitive barriers (30.10%), affective barriers (26.05%), and practical barriers (21.81%).

| Items | n (%) Indicated somewhat or very true |

|---|---|

| In general, mental health problems make it more difficult to find a spouse and romantic partner. | 26 (55.32%) |

| My first inclination would be to get help from parents, friends, religious leaders, or keeping problems to myself when I have mental health issues. | 26 (54.17%) |

| In general, people are avoided when it is revealed that they have mental health problems. | 25 (53.19%) |

| In general, people with mental health problems are not well understood by law enforcement officers. | 25 (53.19%) |

| In general, family members do not like to talk to others about mental health problems. | 23 (48.93%) |

| I may have some extent of nervous, emotional, and other types of mental health issues, but it was not severe enough to seek professional help. | 23 (46.94%) |

| In general, people are treated as less competent by others when they have mental health problems. | 21 (44.68%) |

| I do not think there is a time I have had a nervous, emotional, drug or alcohol problem, and/or other mental health problem. | 21 (42.85%) |

| It is too expensive to seek treatment for mental health problems. | 14 (29.79%) |

| I worry about what others think about mental health treatment. | 14 (29.17%) |

| In general, people are looked down on when their family found out they have mental health problems. | 13 (27.66%) |

| Treatment with mental health problems takes too much time. | 11 (23.40%) |

| I associate shame or embarrassment with sharing mental health problems. | 11 (22.92%) |

| I think these problems will get better by themselves. | 10 (20.40%) |

| It is difficult in receiving adequate mental health services because of insurance coverage. | 9 (19.15%) |

| In general, people with mental health problems are not well understood by medical doctors or other general medical health professionals. | 8 (17.02%) |

| I do not think treatment for these problems from professionals helps. | 5 (10.20%) |

| I feel uncomfortable talking about mental health problems with mental health professionals. | 4 (8.34%) |

Table 2: Participant’s Experiences of Multidimensional Barriers Questionnaire.

Discussion

This study was attempted to establish a comprehensive questionnaire with empirically based items to test out how these barriers very within the Chinese descent participants. Since it was a pilot study tapping perceived barriers with a very small sample, so there were cautions when interpreting the results. Although these results need to be viewed with cautions, they can help researchers and clinicians for future study in this area and it might be useful in improving mental health care and access among Chinese population. Overall, the results of the study were consistent with findings from previous statistic facts that the Chinese population had lower rates of mental health-related services use [4]. Moreover, The findings also confirmed that there were specific barriers that limited the Chinese population from accessing mental health services. The main findings and its implications, limitations, and recommendations are outlined below.

Implications of main findings

Utilization rate: One of the striking findings of the study was the greater rates (78.57%) in no use of any mental health services from professionals, and compared with service providers, Chinese population was more likely to use general medical providers than mental health specialists (12.50% vs. 5.36%) for mental health needs. The results called attention to the general medical providers working with the Chinese population must have the skills and support to manage their mental health needs. It also called attention to the need for an integrative and collaborative relationship between general medical providers and mental health professionals in order to achieve the best client outcomes. In addition, since a small percentage of the Chinese population had previous experience with mental health professionals, this suggested a lack of information and limited access to services among this population. Informal research of service agencies by the current study researchers revealed no Chinese speaking mental health professionals in the areas where the study was conducted.

The limitation of appropriate services and resources was also true in Mainland China as well. In China, the underutilization of mental health services was due to a lack of professional mental health workers, a lack of professional counseling education programs and resources, and an inappropriate/immature mental health system [7,19,22,23]. For instance, China has only 757 mental health facilities and about 20,480 psychiatrists, which is 1.5 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people, a tenth of the ratio of the United States [24,25]. Moreover, the main treatment approaches for individuals with mental illness in China were hospital-based, institutional, psychiatric, and pharmacological treatments; the services provided by psychologists, social workers, and therapists were quite limited [26]. The implications of the study were to develop more culturally appropriate counseling services and outreach programs to promote knowledge and usage of mental health services. For example, in China, the government can encourage the local university to collaborate with an American university to establish a culturally appropriate counseling education system to train more culturally appropriate and professional mental health providers.

Self-perception of need: Consistent with previous studies, the results of the current study suggested that a person’s perception of mental health need played a significant role in service use patterns [17]. Based on the answers of 32 participants, regarding their reasons for not seeking professional help, 40.63% of respondents perceived themselves as not needing mental health help. Since self-recognition of mental health need was the first step in help-seeking behavior, it is important to evaluate how Chinese culture may influence people’s responses. In China, people tend to believe that suppression of personal emotions is a good virtue [8]. This unique cultural value may hinder the Chinese population from recognizing or admitting their mental health needs. Therefore, self-recognition of the need for mental health care among the Chinese population may differ from other racial groups. In the study, 46.94% of participants indicated that they could have a mental health issue but did not view it as severe enough to seek professional help.When providing services to the Chinese population, mental health providers may benefit from knowing that Chinese people who seek mental health care help may have severe levels of mental health need since their distinctive culture may prevent early identification and intervention for mental health issues. Moreover, it might be a good practice for mental health providers to address the importance of holistic health with people who have little awareness of mental health care.

Social and structural stigma: This study revealed that the degree to which the Chinese population utilized mental health services was more strongly affected by the perceived stigma associated with mental illness than by internalized self-stigma. Perceived stigma in this study was evaluated in the category of social and structural stigma. According to Brohan et al. perceived stigma was a reflection of stereotype or prejudices toward mentally ill people in general [27]. In this study, approximately 55.32% of participants felt mental health problems made it more difficult to find a romantic partner, 53.19 % believed that people were avoided when it was revealed that they had mental health problems, and the same percentage of respondents believed that people with mental health problem were not well understood by law enforcement officers. In contrast, internalized self-stigma was the individual’s own feeling toward mental illness or treatment and in this study, self-stigma was assessed in a group of affective barriers [28]. The results showed that 29.17% of participants worried about what others thought about mental health treatment, and 23.40% of participants associated shame or embarrassment with sharing mental health problems. Overall, the percentage rates of social and structural stigma and affective barriers were 42.86% and 26.05% respectively.

This finding is consistent with previous studies that perceived stigma/social and structural stigma associated with mental disorders or mental health treatment significantly reduced the use of mental health services [13,16]. The higher rate of social stigma could explain by the traditional Chinese belief and Confucian values. It viewed mental disorders as resulting from a lack of harmony of emotions or from evil spirits or regard mental disorders as an internal problem that must tolerate rather than biopsychosocial problems that were treatable [22,13]. When providing mental health services to the Chinese population, it might be beneficial for mental health providers to address the fear of being perceived as weak or being the target of discrimination while seeking professional help.

These findings hold important implications for policy and antistigma intervention. Regarding policy change, providing translations services and having cultural competency training for law enforcement officers and health professionals may benefit the Chinese population living in the United States. In terms of anti-stigma, prior studies had shown that both education about mental illness and contact with those with mental illness were effective in reducing public stigma [29]. Antistigma efforts should also focus on Chinese communities and workplaces since societal attitudes toward mental illness and its treatment impacts individual’s attitudes.

Value orientation: In the study, the results highlighted culturally influenced value orientation were associated with mental health service use. Approximately 54.17% of the Chinese participant sample considered talking with parents, friends, or religious leaders or keeping problems to themselves as their first inclination to deal with mental health problems. This finding was consistent with previous research suggesting that Asian American preferred families and social sources of support over professional sources of help [15]. This result may be explained by the characteristics of Chinese collectivist values. Based on collectivistic values, Chinese people usually do not perceive mental illness was a personal matter but as a threat to the harmony of the family; they usually do not distinguish their own interests from the group and tend to see themselves as inseparable from their surrounding social relationships [8,11].

In the survey, 48.93% of respondents believed family members did not like them to talk with others about mental health problems. Chinese cultures often prefer to keep information about family problems within the domain of kinship. Moreover, in collectivist communities, the society often emphasizes the value of saving face and bringing honor to the family and often views disclosure of personal problems as a way of bringing shame to the family and community [8]. This finding reflected cultural norms and attitudes toward help-seeking can shape individuals’ attitudes and preferences toward mental illness and its treatment. Respondents’ tendency of preferring rational coping attitudes called attention to mental health providers to implement culturally appropriate interventions to engage and maintain Chinese population in mental health care. It was due to that many traditional Western psychotherapies oriented to the value of open verbal communication, exploration of intrapsychic conflicts, and a focus on the individuals, which was inconsistent with Chinese’s collectivistic values [8,12]. Some alternative counseling strategies such as integrated social support systems and outreach programming may more effectively help Chinese people deal with mental health concerns.

Limitations and Recommendations

There were cautions when interpreting the results due to several limitations associated with the sample, study methods, and design. First, convenience sampling may have inherent reporting biases. In addition, the majority of the sample (64.81%) who took the study were living in the United States with an average residential year of 12. A positive association between acculturation and services utilization was previously noted in the research [11]. Moreover, the survey was administered online in English. These resulted in underrepresented of the population in understanding the mental health care and service utilization in China. Furthermore, the instrument was designed by the researcher as a pilot study, so the reliability and validity need to be assessed. There was an undecided option in the survey questionnaire, rather than forced choice. Some people opted for undecided option and it could be evaluated whether that should be included in a further version of the instrument or not.

Although these results need to be viewed with some caution, the findings suggested potential directions for future study. The questionnaire should be further utilized with a more expansive sample. In particular, it should be administered to participants living in China as they may not have been influenced by Western values. The survey questionnaire could also be administered in Mandarin. In addition, future research could evaluate the instrument to see if it is useful for other Asian populations (e.g., Japanese, Korean, etc.). It might be beneficial to have a qualitative focus group regarding access to mental health care and efforts to reduce the stigma. Research could also extend to an assessment of access and quality problems in mental health services to increase providers’ competence and effectiveness of services for minority populations.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, the study provided some meaningful data in understanding the barriers that could hinder the Chinese people from seeking professional mental health help. Recognizing and understanding the barriers are not only beneficial to the mental health providers in delivery more culturally appropriate and effective mental health care but also benefited from the overall development of China’s human resources. This study found that social and structural stigma and cultural value orientation were particularly relevant to the service use of the Chinese population. Such trends of service utilization provided some potential implications, such as calling a provider with more appropriate services concerning to low awareness of mental health needs and collectivistic value orientation, policy change regarding structure barriers, and anti-stigma interventions relating to social stigma and discrimination. Negligence in dealing with these trends may lead to the continued high prevalence of mental illness and the huge treatment gap between mental health needs and mental health treatment among the Chinese population. Therefore, more studies that include a larger sample population of Chinese especially in China should be carried out to better examine the barriers to mental health services use by the former.

References

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B (2004) The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 82: 858-886.

- Lim SL, Lim BKH, Michael R, Cai R, Schock CK (2010) The trajectory of counseling in China: past, present, and future trends. J Couns Dev 88: 4-8.

- Wong DFK, Li JCM (2012) Cultural influence on Shanghai Chinese people’s help-seeking for mental health problems: Implications for social work practice. Br J Soc Work 44: 868-885.

- Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, et al. (2009) Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: An epidemiological survey. Lancet 373: 2041-2053.

- WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology (2000) Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ 78: 413-425.

- Radio Free Asia (2004) Concerns rise over China’s mental health problems. Washington DC, USA.

- Liu J, Ma H, He YL, Xie B, Xu YF, et al. (2011) Mental health system in China: History, recent service reform and future challenges. World Psychiatry 10: 210-216.

- Leong FTL, Lau ASL (2001) Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Ment Health Serv Res 3: 201-214.

- Kung WW (2004) Cultural and practical barriers to seeking mental health treatment for Chinese Americans. J Community Psychol 32: 27-43.

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi, DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, et al. (2007) Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health 97: 91-98.

- Jang Y, Kim G, Hansen L, Chiriboga DA (2007) Attitudes of older Korean Americans toward mental health services. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 616-620.

- Jimenez DE, Bartels SJ, Cardenas V, Alegría M (2013) Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among racial/ethnic older adults in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28: 1061-1068.

- Park JE, Cho SJ, Lee JVY, Sohn JH, Seong SJ, et al. (2015) Impact of stigma on use of mental health services by elderly Koreans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50: 757-766.

- Spencer MS, Chen J, Gee GC, Fabian CG, Takeuchi DT (2010). Discrimination and mental health-related service use in a national study of Asian Americans. Am J Public Health 100: 2410-2417.

- Yeh J, Wang YW (2000) Asian American coping attitudes, sources, and practices: Implications for indigenous counseling strategies. J Coll Stud Dev 41: 94-103.

- Cheng ZH, Tu MC, Li VA, Chang RW, Yang LH (2015) Experiences of social and structural forms of stigma among Chinese immigrant consumers with psychosis. J Immigr Health 17: 1723-1731.

- Nguyen D, Bornheimer LA (2014) Mental health service use types among Asian Americans with a psychiatric disorder: Considerations of culture and need. J Behav Health Serv Res 41: 520-528.

- Yang LH, Chen FP, Sia KJ, Lam J, Lam K (2014) “What matters most:” A cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Soc Sci Med. 103: 84-93.

- Cook AL, Lei A, Chiang D (2010) Counseling in China: Implications for counselor education preparation and distance learning instruction. J Int Couns Edu 2: 60-73.

- Erford BT (2015) Research and evaluation in counseling (2nd edn) Cengage Learning, Stamford, USA.

- American Counseling Association (2014) ACA code of ethics. USA

- Kramer EJ, Kwong K, Lee E, Chung H (2002) Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans. West J Med 176: 227-231.

- Wong DFK, Zhuang XY, Pan JY, He XS (2014) A critical review of mental health and mental health-related policies in China: More actions required. Int J Soc Welf 23: 195-204.

- Liu C, Chen L, Xie B, Yan J, Jin T, et al. (2013) Number and characteristics of medical professionals working in Chinese mental health facilities. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 25: 277-285.

- Xiang YT, Yu X, Sartorius N, Ungvari GS, Chiu HFK (2010) Mental health in China: Challenges and progress. The Lancet 380: 1715-1716.

- Szymanski J (2012) Mental health in China: An interview with experts leading the field of Chinese mental health. Psychology Today, New York City, USA.

- Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Thornicroft G (2010) Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: A review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res 10: 80.

- Pepin R, Segal DL, Coolidge FL (2009) Intrinsic and extrinsic barriers to mental health care among community-dwelling younger and older adults. Aging Ment Health 13: 769-777.

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N (2012) Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv 63: 963-973.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi