Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 2 Issue: 2

Depression among Students of a Professional Degree: Case of Undergraduate Medical and Engineering Students

| Fatimah N*, Hasnain Nadir M, Kamran M, Shakoor A, Mansoor Khosa M, Raza Wagha M, Hasan M, Arshad A, Waseem M and Afzal Kayani S | |

| Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Shaikh Zayed Medical Complex, Lahore, Pakistan | |

| Corresponding author : Dr. Nafeesah Fatimah, House Officer Department of Internal Medicine, Shaikh Zayed Medical Complex, Lahore, Pakistan Tel: 0092-333-4243281 E-mail: nafeesahjavaid@gmail.com |

|

| Received: February 01, 2016 Accepted: April 15, 2016 Published: April 19, 2016 | |

| Citation: Fatimah N, Hasnain Nadir M, Kamran M, Shakoor A, Mansoor Khosa M, et al. (2016) Depression among Students of a Professional degree: Case of Undergraduate Medical and Engineering Students. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 2:2. doi:10.4172/2471-4372.1000120 |

Abstract

Objectives: Depression amongst undergraduates has been widely reported, however its correlates have been inadequately identified. Furthermore, a comparison, between the two most stressful curriculum is lacking. We aimed to highlight the prevalence and predictors associated with depression in Undergraduate Medical and Engineering students, with the hope of guiding mental health experts to implement policies that would benefit said individuals.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study in two institutes of Lahore, Pakistan namely Shaikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al-Nahyan Medical College, and University of Engineering and Technology, in 2013. A structured, self-administered questionnaire was used to segregate the predictors associated with depression, and Beck’s Depression Inventory II was used to diagnose depression.

Results: The overall response rate was 94.7%. Among the 451 responders, 87 were clinically depressed with a mean BDI-II score of 28.72 ± 5.144. The difference in prevalence amongst the two, 22.5% for Engineering and 15.0% for Medical was statistically significant (P = 0.047, 95% Confidence Interval). There was, however no significant difference in the severity of depression or gender preponderance.

Using Binomial Logistical Regression Analysis the predictors found to be associated with depression irrespective of gender and institute were ‘always observed arguments between parents’, ‘loved ones taking drugs’, ‘college discontentment’, ‘always feeling like daily workload is too much’, ‘never feeling satisfied with academic performance’, ‘sometimes feeling someone else is being favoured academically’, ‘difficulty meeting parents’ expectations’, ‘always feeling bullied’, ‘always felt socially isolated’.

Predictors more significant in Medical students were ‘not satisfied with living environment’, ‘career-personal life conflict’, ‘college discontentment’, and ‘always feeling bullied’.

For Engineering students, ‘dropping out of college’ , ‘not being satisfied with hair’, ‘always felt socially isolated’, ‘recent breakup’, and ‘sexual abuse’ were significant.

Conclusion: The results identify possibly modifiable psychosocial and academic predictors of depression which need to be further addressed through prospective studies.

Keywords: Depression; Medical education; BDI-II; Undergraduates

Keywords |

|

| Depression; Medical education; BDI-II; Undergraduates | |

Introduction |

|

| Every third university student has experienced depression [1]. In this global system will Pakistan be far behind? | |

| Post-industrial societies have become highly demanding with the resultant stress upon youth to excel in their career. In their efforts to survive in competitive environment, a substantial proportion of youth experiences significant psychological distress ranging from stress and anxiety to depression and suicidality [1-3]. The vulnerability to depression is further augmented by the lack of a buffering role of primary group relations in post modern society. Susceptibility of youth to depression in their student life has been documented in the Western world [2-5]. In the present global system, the Pakistani society is undergoing similar transformations where the complexity of the competitive milieu appears to be all pervasive. Professionals, especially those from health and engineering caders, enjoy a relatively high place in the hierarchy of occupations in Pakistan. Given the limited openings at different tiers of the career – starting from admission into degree programs, successful completion of the coursework to getting selected for a posting – each tier is highly competitive and may predispose young adults to depression. | |

| Depression in young adults negatively impacts their learning abilities [2] and just by living in such a competitive environment they are likely to further recede into bipolar illness later in their lives [6]. Various predictors have been identified in previous studies that are found to be associated with depression among young adults ranging from personal factors to institutional and social factors [1,2,5,7-13]. Environmental and institutional factors that predispose undergraduate students to depression include academic pressure, rising parents’ and teachers’ expectations, hindrances to goal achievement, favouritism, vastness of the curriculum, workload, student abuse, change in role from students to professionals, recent breakup, and childhood adversities [1,2,5,7-12]. Persistent family effect was also seen i.e. the adults whose first-degree relatives were depressed were two to three times more likely to get depressed themselves [13]. | |

| Among young college-going adults, students pursuing degrees in medicine or engineering appear to be exposed to relatively higher levels of mental stress compared to others. One important reason for this reality appears to be the tough competition for limited openings in these relatively prestigious professions, thereby generating a stressful environment, leading to depression. This observation is supported by some sporadic findings from Pakistani studies. A snapshot study [11] found a 43.9% prevalence of depression and anxiety in medical students. Comparatively, the prevalence of depression among engineering students was found to be much higher, with approximately 73.8% of students suffering from depression [14]. For the authentication of these findings, more research is needed. | |

| To address this grave issue, mental health professionals need a scientific basis to devise methods to counter depression among undergraduate students. Also, the wellness curricula can better function if they are designed by studying the specific correlates and predictors of depression among young adults as they tend to vary with age. Furthermore, there is a lack of comparison amongst the predictors that favour depression and the prevalence of depression in particular professional academic settings. In Pakistan, getting admission into a medical or engineering professional schools is highly competitive and stressful with high familial and societal pressure and expectations to achieve excellence. Such an observation and experience led to the driving question of the current study - what is the difference in the prevalence and predictors of depression among medical and engineering students of Pakistan?. | |

| The objectives of the current study are: | |

| • to assess and compare the prevalence of depression among the undergraduate medical and engineering students and | |

| • to determine the specific predictors associated with depression among medical and engineering undegraduates. | |

Methods |

|

| A cross-sectional survey was conducted on a representative sample of 196 out of 400 medical students from a medical college of Lahore and 280 out of 1002 engineering students from an engineering university of Lahore admitted in the year 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012. The sample size of four hundred and seventy-six was calculated with an allowable error of 5%, confidence interval of 95% and 15% for non-responders. Students were selected through stratified random sampling. | |

| By taking written informed consent and preserving anonymity, a structured, closed-ended, self-administered questionnaire was used comprising of three parts: demographic variables, Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Predictors of Depression Questionnaire (PDQ). | |

| The prevalence of depression was determined by using the BDIII [15,16] for which a research license agreement was entered into by and between NCS Pearson, Inc., a Minnesota Corporation, and N.F. (corresponding author). BDI-II scores range from 0 to 60, with a cut-off of ≥ 21 for ‘clinical depression’ and <21 for ‘no depression’ with higher scores indicating severe depressive symptoms. Gradation of the severity of depression was as follows: 1-10 ‘normal ups and downs’, 11-16 ‘mild mood disturbance’, 17-20 ‘borderline clinical depression’, 21-30 ‘moderate depression’, 31-40 ‘severe depression ‘and > 40 as ‘extreme depression’(Beck et al.). The BDI-II scores were also broadly grouped into three categories: 1-16 as low depression, 17-30 as moderate depression, and > 30 as significant depression. | |

| Our non-exhaustive list of fifty predictors of depression was identified and detailed by extensive literature review under the guidance of a team of three psychiatrists, one psychologist, two medical educationists and two public health professionals. The list of these predictors was then used to formulate the PDQ. The predictors were broadly categorized into three headings: ‘personal factors’, ‘institutional/academic factors’, and ‘social factors’. These potential predictors were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’. The PDQ was pilot-tested on forty students, which included an equal number of medical and non-medical students, i.e. 20 medical and 20 non-medical students to assess the validity and reliability. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated, which came out to be 0.624, hence a few questions were removed and finally administered to the study population. | |

| The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean score of the BDI - II was calculated for the overall sample and separately for the medical and non-medical students. To analyze the statistical significance of the differences in the severity of depression between the two groups, independent samples t-test was applied. For discrete variables, χ2 test was used and Fisher’s exact was applied when n ˂ 5. Binomial Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors associated with depression. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) were calculated and overall, p values of ≤ 0.05 were taken to be statistically significant with the confidence interval of 95%. | |

Results |

|

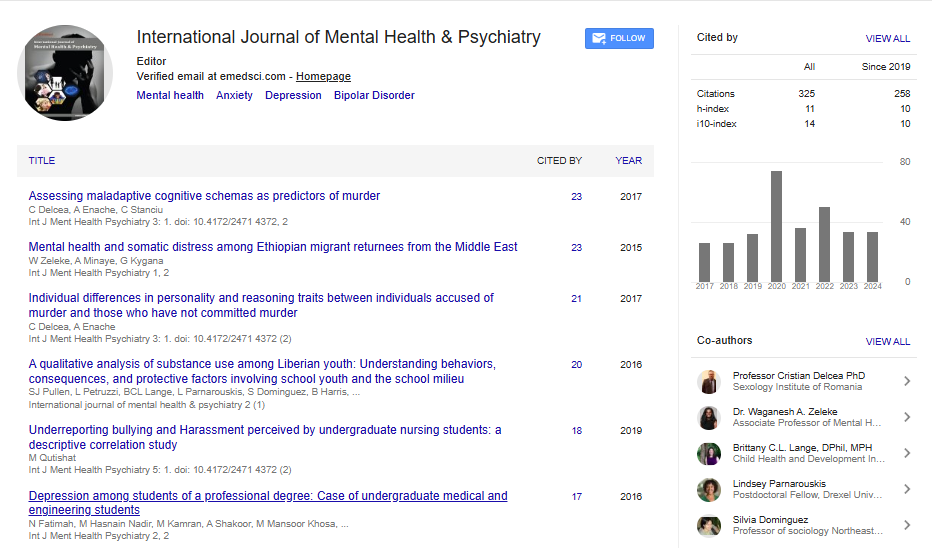

| Out of the targeted 476 students, 451 returned the completed questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 94.7% [98.5% (n=193) for medical and 92.1% (n=258) for non-medical students]. The characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. | |

| Table 1: Characteristics of undergraduate medical and engineering students. | |

| Overall, mean BDI-II score of the students was 13.78 ± 9.130 (mild mood disturbance). Mean BDI-II scores of medical students was 13.68 ± 8.463 while for engineering students, it was 13.86 ± 9.614, which was reflective of mild mood disturbance. This difference was statistically insignificant. | |

| Overall, 19.3% (87/451) students studying in the two institutes of Lahore were found to be clinically depressed (mean BDI-II score of depressed students = 28.72 ± 5.144, ‘moderate depression’). Moderate depression was found in 17.7% (55/311) male students (mean BDI-II score = 28.47 ± 6.874), while 22.9% (32/140) female students (mean BDIII score = 29.16 ± 6.401), with a statistically insignificant difference. | |

| Amongst engineering students, 22.5% (58/258) students were found to be suffering from clinical depression (mean BDI-II score of depressed students = 28.47 ± 6.934, ‘moderate depression’). | |

| Amongst medical students, 15.0% (29/193) of students had clinical depression (mean BDI-II score of depressed students = 29.24 ± 7.293, ‘moderate depression’). There was no statistically significant difference in clinical depression amongst medical students studying in pre-clinical years i.e. years 1 and 2 (overall mean BDI-II score for pre-clinical years = 14.66 ± 8.634, ‘no depression’) and clinical years i.e. years 3 and 4 (overall mean BDI-II score for clinical years = 12.71 ± 8.220, ‘no depression’). | |

| The independent samples t-test showed no statistically significant difference in the severity of depression between engineering and medical depressed students (mean BDI-II score = 28.47 ± 6.934 versus 29.24 ± 7.239 respectively). | |

| Using χ2 test, the difference in the point prevalence of depression observed amongst non-medical and medical students [22.5% (58/258) versus 15.0% (29/193) respectively], was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 3.941, 95% CI, p = 0.047). | |

| The differences in the level of depression with respect to gender and institute are detailed in Table 2. | |

| Table 2: Percentage prevalence of level of depression by profession and gender among undergraduate students. | |

| Predictors | |

| Personal Factors: By using Binomial Logistic Regression Analysis, the personal predictors associated with depression irrespective of gender and institutes are ‘unsatisfied with hair, complexion and height’, ‘sleep and appetite disturbance’, ‘loved ones taking drugs’, ‘difficulty paying college dues’, ‘reduced interest in daily activities’, ‘sexual abuse’ and, ‘arguments with parents and between parents’ (Table 3). | |

| Table 3: Predictors associated with depression among undergraduate students. | |

| Social Factors: Among the social factors, the predictors found to be associated with depression irrespective of gender and institute are ‘recent break up’, and ‘social isolation’ (Table 3). | |

| Academic Factors: The academic factors found to be associated with depression irrespective of gender and institute are ‘college discontentment’, ‘bullying’, ‘daily workload’, ‘always having difficulty coping with exam frequency’, ‘academic performance dissatisfaction’, ‘career-personal life conflict’, ‘difficulty meeting teachers’ and parents’ expectations’, ‘favouritism’, ‘difficuty communicating with authorities’, ‘dropping out of college’, and ‘not being engaged in the preferred extra-curricular activities’ (Table 3). | |

| The factors associated with medical and engineering students are illustrated in Table 4 and 5 respectively. | |

| Table 4: Predictors associated with depression amongst undergraduate medical students. | |

| Table 5: Predictors associated with depression in undergraduate engineering students. | |

Discussion |

|

| Substantial amount of scientific evidence is available on the prevalence of depression and stress among medical students [17-19] but there is a dearth of national data for measuring the differences in prevalence and predictors of depression among students of two different professional curricular settings like medicine and engineering. | |

| Engineering students exhibited more clinical depression (22.5%) than medical students (15%); showing a statistically significant difference. These figures corroborate the results of the multischool study [10] that revealed 12% prevalence of screened major depression among medical students and residents. A study conducted on the general population of Pakistan found a mean point prevalence of 34% for depression as well as anxiety [20] while in the general population of Lahore, the point prevalence of depression was found to be 53.4% [21]. A Turkish study reported the point prevalence of 21.8% of depression amongst the students [22] which correlates with the 19.3% overall point prevalence of depression in the undergraduate students in our survey. The lower prevalence of depression among college students than the general population of Pakistan correlates with the previous studies that identified the lower educational level to be a risk factor for depression. As our study subjects are young adults in various years of their professional degree programs, their education might be a protective factor against depression. Intelligence too can be considered a protective factor as top students with high IQ are selected for admission in these two professional schools in our context. | |

| Furthermore, it was found that academic year has no association with the severity of depression both in medical and engineering undergraduates, which is in sheer contrast to the study conducted at Saudi Arabia [17] which found highly significant association between study year and depression. On the other hand, a study conducted on second and third year Chinese medical students reported no association of depression and study year [3]. However, a few studies from Pakistan report a declining pattern of depression from the first to final year [11,23]. Our findings can have many possible reasons: as the medical college where the study was conducted admits comparatively fewer number of students, it is possible that effective student-teacher interaction has facilitated a smooth transition from pre-clinical to clinical years. But this is just a speculation as baseline data on depression of the students at the time of admission was not available. The level of depression and its association with academic year among undergraduate needs to be studied with the help of longitudinal studies to better understand the relationship. | |

| Gender is often considered a factor predisposing individuals to depression [24-26]. We found that overall there was no difference in the level of depression due to gender. However, there was some difference in the prevalence of depression between the students coming from the two groups. Within the medical group, no difference in the prevalence of depression was found among male and female students. However, the data from the engineering groups appeared to be a little intriguing. Here, some difference, although not significant, was found due to gender. Data in Table 2 showed that at the low and moderate levels of depression, difference between the male and female students was more than 10 percentage points. The proportion of female students at the moderate level of depression was substantially higher than their male counterparts (Table 2). Comparing the medical students with those of the engineering, there was not much difference between the percentages of males at three levels of depression. Interestingly, the proportion of female engineering students suffering from moderate depression was substantially higher than the males (22.3 % for males; 34.0% for females). One explanation could be the relatively late entry of women in the field of engineering and presumably they were still experiencing the male dominance in the profession. | |

| Among the personal factors, perceived physical problems (not satisfied with height or complexion), sleep and appetite disturbance and substance abuse by loved ones are the major predictors associated with depression in medical and engineering students, which is highly consistent with other studies [10,14,23]. Additionally, sexual abuse (p = 0.033) is another alarming factor associated with depression among engineering students . Instant measures should be taken for the protection against sexual harassment and violence as it insidiously adds to the psychological plight of the students during their crucial academic years. | |

| Among the social factors, ‘social isolation’, and ‘recent break up’ were found to be the predictors of depression among medical students, which are also fairly consistent with the study conducted amongst the students of CMH, Lahore [12]. While in males, ‘smoking’ is another important factor associated with depression because of its relatively easy access to the males and acceptability in the society [28]. The only social variable associated with depression in non-medical students is ‘recent breakup’. This has a plausible explanation in terms of the onslaught of western cultural values which have made extramarital relations acceptable in the society and has left the youngsters in the quagmire of emotional turmoil. | |

| Among the academic/institutional variables, ‘not feeling content with institution’, ‘always feeling like workload is too much’, ‘not meeting teachers’ expectations’, ‘always feeling like not being engaged in preferred extra-curricular activities’, and ‘career-personal life conflict’ were linked with depression in students and too were consistent with other regional studies [1,11,12,14,29]. Interestingly, the other common predictor found in the students of both the institutions was ‘always feeling like someone else is being favoured in academics/extra-curricular activities’. Its probable explanation lies in the fact that a high level of favouritism is practiced all over the country and sadly the educational institutions are also affected by this. The presence of favouritism can be very discouraging for the intelligent but shy students whose abilities may remain unexplored throughout their life. Another interesting finding was that bullying was only associated with depression in male students, in both the professional settings reflecting that in our cultural context bullying is considered more humiliating by male gender compared to females. Moreover, college discontentment and career-personal life conflict was found to be associated with depression in female medical students which can be explained by the fact that in our part of the world; society and family has greater expectation from females than males. Hence, it can be argued that it gets difficult for females studying in inherently demanding medical schools to meet family expectations without at the same time compromising education which could possibly lead to them ending up in the dilemma of a conflict between their career and personal lives, which may predispose them to depression. | |

| Although our study is limited to two institutions and thus can not be generalized as well as having a cross-sectional design further reduces its credibility to deduce a temporal or cause-effect association, but still it sheds some light on the psychological plight of the medical students as well as their counterpart engineering students. Our findings need validation by multi-institutional longitudinal studies to study the causeeffect relationship. The personal, academic/institutional, and social predictors need to be explored in further detail. | |

Conclusion |

|

| We found that young adults show a significant prevalence of depression which can have far-reaching consequences and various modifiable predictors predispose these young adults to depression. The multitude of institutional factors identified in our study show that teachers, institutional policy makers, and curriculum developers need to modify both the written and hidden curriculum in a way that makes it more student-friendly. Moreover, there is a need to integrate the reactive and pro-active wellness curricula in our institutions to help students cope with demanding university education. In short, psychologists, mental health professionals, teachers, and our institutional policy makers need to join hands to formulate potent and successful strategies to address this highly sensitive matter. We need to provide counselling and stress management to our students so that there are a minimal depressive episodes and maximum productivity during this the most crucial period of their lives. | |

Acknowledgments |

|

| Authors would like to acknowledge | |

| • Prof. Dr. Ayesha Humayun Shaikh, Head, Deaprtment of Community Medicine and Public Health for her continuous guidance and support in helping prepare this manuscript. | |

| • Dr. Hyder Ali Khan, Demonstrator, Department of Commununity Medicine and Public Health for his help in data analysis. | |

| • Dr. Sameen Mohtasham Khan, House Officer, Department of Internal Medicine for her help in data analysis. | |

Ethical Standards |

|

| The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi