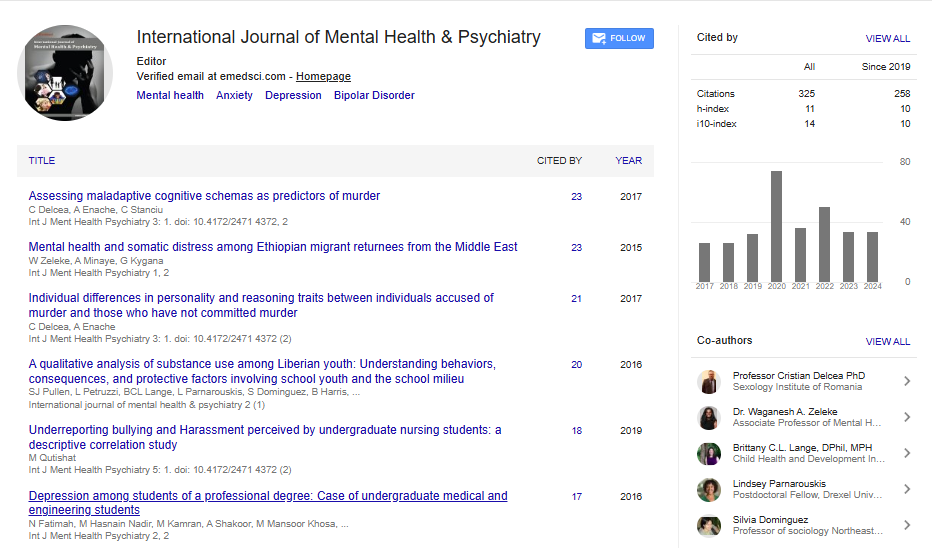

Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 11 Issue: 1

Paternal Postpartum Depression and Associated Factors among Partners of Women Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months in Dessie Town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023: Community Based Cross Sectional Study

Abdulaziz Assefa1*, Amare Werkie2, Mandefro Assefaw2 and Aynalem Belay1

1Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Ethiopia

2Department of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Abdulaziz Assefa

Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Ethiopia

E-mail: abdulazizmom19@gmail.com

Received date: 02 November, 2023, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-119086;

Editor assigned date: 06 November, 2023, PreQC No. IJMHP-23-119086 (PQ);

Reviewed date: 20 November, 2023, QC No. IJMHP-23-119086;

Revised date: 16 June, 2025, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-119086 (R);

Published date: 23 June, 2025, DOI: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000293

Citation: Assefa A, Werkie A, Assefaw M, Belay A (2025) Paternal Postpartum Depression and Associated Factors among Partners of Women Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months in Dessie Town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023: Community Based Cross Sectional Study. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 11:2.

Abstract

Background: Paternal depression among fathers of new-born is a new concept in Ethiopia. It is an emerging public health concern because; it produces insidious effects on the well being of new-born as well as on the whole family, which is currently under screened, under diagnosed and undertreated. However, there is limited evidence on the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression and its predictors among partners of women in Ethiopia.

Methods: A community based cross-sectional study was conducted among 634 partners of postpartum women in Dessie town from January 10-Feburary 10, 2023 to assess the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression and associated factors among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months. The data were collected using a structured and pretested questionnaire though face-to-face interviews and the data were cleaned, edited, and entered into Epi-data version 4.6, and analysed SPSS version 26. The Edinburgh postpartum depression scale was considered at a cutoff point ≥ 10 to detect depression.

Result: A total of 610 fathers were interviewed with a response rate of 96.2% and the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression was 19%, (95% CI: 16.0, 22.3). This study showed that; not comfortable with family income (AOR=2.32 (95% CI: 1.16, 4.66)), substance use (AOR=2.48 (95% CI: 1.22, 5.05)), experience of childbirth (AOR=1.89 (95% CI: 1.02, 3.50)), unplanned pregnancy (AOR=2.81 (95% CI: 1.50, 5.25)) and infant sleep problem (AOR=3.59 (95% CI: 1.80, 7.18)), were significantly associated with paternal depression.

Conclusion and recommendations: This study revealed that almost one-fifth of fathers had paternal postpartum depression. Not comfortable with family income, substance use, experience of childbirth, unplanned pregnancy and infant sleeping problem were significantly associated with paternal postpartum depression. This suggests the need to provide health education to decrease substance use and counselling to the utilization of family planning to minimize unplanned pregnancy and supports offer to multiparous fathers

Keywords: Paternal postpartum depression; Edinburgh postpartum depression scale; Ethiopia

Introduction

Paternal depression is a clinically significant mental health problem for male partners. Conversely, depression among the fathers of new borns is also termed as Paternal Postpartum Depression (PPPD) or “sad dads” [1].

Most studies use the definition for Maternal Postnatal Depression (MPPD) to define paternal postpartum depression [2]. According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, maternal postpartum depression is defined as an episode of major depression symptoms occurring in the 4 weeks following delivery [3].

The onset limitation of 4 weeks has been criticized in different studies, as it does not reflect the epidemiological evidence. In both clinical practice and research, the term postpartum depression refers to depressive episodes occurring in the first year postpartum period. The 12 month timeframe was chosen, because the most significant change and readjustment in family and work life occurred in this period.

Studies show that approximately 10% of fathers develop postpartum depression, typically beginning in the first 12 months after a baby’s birth, with the highest number between 3 and 6 months after birth which is later than when women develop postpartum depression.

The symptoms associated with paternal postpartum depression include insomnia or hypersomnia, eating disorder, fatigue, sadness, crying, anxiety and feeling of guilt related to caring for their infant. While, many postpartum depression symptoms are similar for fathers and mothers, some symptoms are unique to men. These symptoms include irritability, indecision, violent behavior and substance abuse [4].

The risk factors are poor marital relationships, lack of family support, father’s history of depression, infant sleeping disorder and substance use as ecological factors and changes in levels of testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, vasopressin, and prolactin as biological factors [5].

Paternal depression is widely overlooked despite being the most common mental health problem among fathers, and it affects all aspects of family life [6]. Men are under screened, under diagnosed and undertreated for Postpartum Depression (PPD) and other postpartum mental health problems. The prevalence of paternal postpartum depression is approximately 10%, which is a significant public health issue. Therefore, it is not widely acknowledged and there is a dearth of research.

The prevalence of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women in different studies varies widely. The study shows that approximately one in ten fathers develop paternal postpartum depression. The prevalence of paternal postpartum depression ranges from 1.2% to 25.5%, and is most likely to experience a first onset of paternal postpartum depression in the first 3 to 6 months of the postpartum period [7].

A study was performed in Finland to synthesize the evidence on new mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of PPD, and the findings showed that 10% of fathers experienced depressive symptoms [8]. Additionally, in another study, 28.3% of fathers in Pakistan, and 13.6% of fathers in Saudi Arabia had postpartum depression [9,10]. In Nigeria, the prevalence was 8.9%, which is an important finding in this study. When fathers of newborns were followed up for 6 weeks, 1 in 20 developed depression symptoms [11].

Risk factors have been associated with PPD for male partners including paternal factors such as family income, substance use, history of depression and relationship factors such as marital status, poor professional support, poor marital/parental relations and poor family support. Infant and environmental factors like congenital anomalies of infants, place of health care, infant sleeping problems and history of loss of child [12].

Depression in fathers during the first year of child life can have a negative impact on fathers, such as developing chronic depression, suicidal behavior, substance abuse disorder and socioeconomic problems. It also affects families, including increasing social, behavioral, cognitive and emotional developmental problems in their children, poor parenting behaviors and increasing conflicts in the marital relationship.

Children who live with fathers with depression or other mental illness have a 33 to 70% increased risk of developing emotional and behavioral problems [13].

According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendation, depression can be diagnosed and treated in primary health care centers, and midwives have a good opportunity to diagnose fathers’ PPD because of their proximity to families [14]. The American Academy of Pediatrician (AAP) acknowledged that paternal depression during the postpartum period as a clinical problem yet called for pediatricians to screen fathers at the 6 month postpartum visit. The National Perinatal Association (NPA) encourages screening fathers for depression at least twice during the first postpartum year [15].

Strategies in Ireland can be implemented by midwives who initiate screening and outreach programs for fathers as well as to provide information about the potential effects of the transition to parenthood on mental health. Currently in Japan, midwives or public health nurses visit all families within four months after childbirth [16].

In developing countries including Ethiopia, guidelines for assessing paternal mental health are not established, even in areas where midwives are directly involved with pregnancy and postpartum care, Although the WHO has emphasized providing integrated maternal and child health services, new fathers’ mental health has not yet been embedded in these programs. Additionally, there are different literature on the role of fathers, the benefits of paternal involvement in child care and their functioning within families [17].

Several countries, including Ethiopia, have designed and implemented paternity leave policies to help fathers adapt to new fatherhood and have positive effects on parental mental health. However, it is a very short period, which is insufficient, particularly in private sectors and it is important to note socially accepted norms that designate mothers as primary caregivers, while fathers are expected to provide income for family or secondary caregivers that results in negative social outcomes [18].

However, the problem has been studied in developed countries that might have limited generalizability to the developing country population due to the difference in cultural and social values. There are also limited studies from developing countries, whose men have huge environmental and sociocultural vulnerability. As far as the literatures search concerned, there is no studies in Ethiopia regarding to PPPD. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of PPPD and associated factors among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Materials and Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in Dessie town, Amhara Regional state, Northeast Ethiopia. It is one of the city administrations in Amhara Region, which is geographically located 480 km from the regional town (Bahir Dar) and 401 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It has a latitude and longitude of 11°07'60.00" N 39°37'.99" E and an elevation of 243 meters above sea level.

Dessie town has 26 kebeles, the lowest administrative level in Ethiopia (18 are urban kebeles and 8 are rural kebeles). Based on the Dessie town population statics report of 2014 E.C, the town has an estimated total population of 285,530 of whom 141,338 are men and 144,192 are women. There are 9,660 wives gave birth in the last year in Dessie town.

There are two government hospitals, 8 public health centers,14 health posts, 3 private hospitals, and 45 private clinics in the town. The study was conducted from January 10-February 10, 2023.

Study design

A community based cross-sectional study was implemented.

Population

Source population: All fathers whose wives gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town were the source of population.

Study population: All fathers whose wives gave birth in the last 12 months and who are residents in randomly selected kebeles of Dessie town were the study population during the data collection period.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: All fathers whose wives gave birth in the last 12 months and who are residents for at least six months in randomly selected kebeles.

Exclusion criteria: Fathers who were seriously ill and unable to respond to questions during the data collection period were excluded from this study.

Sample size determination

The required sample size of the study was determined by using a single population proportion formula.

n=(Zα/2)2 P(1-P)/d2

Where,

n=The desired sample size

Zα/2= The standardized normal distribution value for 95% CI=1.96

d=The margin of error to be tolerated (5%)

P=by considering 50%, since the prevalence of PPPD in Ethiopia is not known.

n=(1.96)2 0.5(1-0.5)/(0.05)2

n=384

A design effect of 1.5 was used. Because, the sampling procedure is multistage stratified sampling and becomes 576, then none response rate of 10% was added.

Therefore, the final sample size for this study is 634.

Sampling procedure

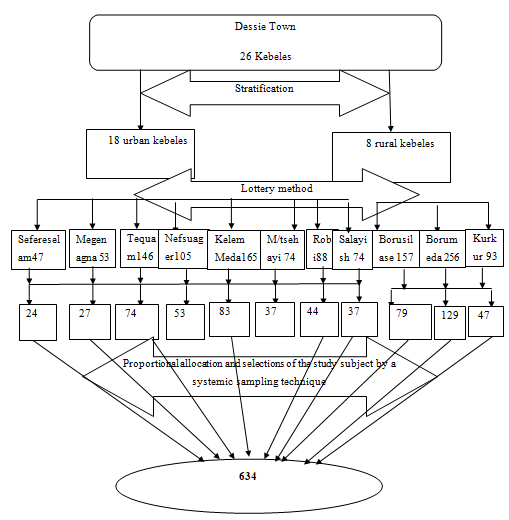

A multistage stratified sampling technique was used. The first 26 kebeles were stratified into two strata rural and urban. Then, three random kebeles were selected from 8 rural kebeles and 8 kebeles from 18 urban kebeles by using the lottery method.

A total of 11 kebeles were included in the study. Then, proportionally allocated the study participants for each selected kebele. To allocate, we used the formula ni × n/N, where ni=total fathers during the postpartum period in each of the selected rural or urban kebeles, and Nis the total number of fathers during the postpartum period in both urban and rural kebeles.

A total of 752 fathers lived in 8 selected urban kebeles and 506 fathers lived in 3 selected rural kebeles. From 11 kebeles, total numbers of fathers were 1258. The sample sizes by using thus formula, 379 fathers were selected from 8 urban kebeles and the remaining 255 fathers were selected from 3 rural kebeles.

Finally, a systematic sampling technique was used to select each individual of fathers during the postpartum period from each kebeles in every Kth interval taking K=N/n, K1 (Sefereselam)=47/24=1.96≈2, K2 (Nefsuager)=105/53=1.98≈2, K3 (Kurkur)= 93/47=1.98≈2, and almost all kebeles Kth interval ≈2.

The first sample was selected randomly, and then samples were taken every Kth interval, where N is the total fathers from selected kebeles and n is the sample size for selected kebeles (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of sampling procedure for paternal postpartum depression and associated factors among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Dependent variable

Paternal postpartum depression

Independent variables

Paternal factors: Age, religion, residence, educational status, employment status, number of newborns, family income, comfortable with family income, substance use, history of depression and experience of childbirth.

Relationship factors: Relationship with parents, marital status, marital relation, number of wives, relative mental illness, friend support, family support and professional support.

Infant and environment factors: Residence of wife after delivery, housing status, planned/unplanned pregnancy, duration of postpartum period, attended ANC, mode of delivery, presence/absence of male partner at delivery of a baby, GA of the pregnancy, congenital birth problems, place of delivery, infant sleeping problem, and history of loss of child.

Operational definition

Paternal postpartum depression: In this study paternal depression during postpartum period was defined as when the cumulative score of Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) was 10 or above.

Family support: Fathers were asked an item regarding their perceived received social support from individual living together as a family member. An item started with the phrase: In my parenting role, I often receive support from my families, with response options Yes/No.

Poor marital relationship: when partners experience the lack of intimacy and the loss of female partner’s interest in a sexual relationship, and sense of lower satisfaction and disruption of relationship with their spouse, with response options Yes/No.

Comfortable with family income: When the male partners not having worry much about money and having sense of satisfaction situation. It is not defined by amount of money rather relative to personal value and other factors, such as overall wellbeing and happiness, with response options Yes/No.

Substance use: When the male partners used any one or more of the substances such as fabricated or local alcohol, chat chewing, cigarette or tobacco smoking and others such addictive substance and measured by at least one yes response prior to the interview irrespective of its dose and frequency.

Infant sleeping problem: Infant sleeping problem was defined based on parent’s response of infant sleep duration as irregular or not sufficient.

Data collection tools and procedures

The data were collected using structured, pretested Amharic questionnaires through face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire was prepared by reviewing different published studies and modified to the objective of this study.

The questionnaire included paternal factors, relationship factors, infant and environment factors and EPDS screening tools. The data were collected by five BSc midwives who had prior experience in data collection and one in MPH was assigned for supervision.

The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) identifies depression symptoms over the preceding 7 days. The scale has 10 items and each item of the scale is scored from 0 to 3, yielding a total range of 0–30. The score of question numbers 1, 2, and 4 was the first choice scored as 0, the second choice was scored as 1, the third choice was scored as 2 and the last choice was scored as 3. The score of question numbers 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 was scored first as 3, second as 2, third as 1 and last as 0.

The EPDS is an easy to self-administered 10-item questionnaire that was originally designed to screen mothers at risk of perinatal depression. Numerous studies have used this scale to assess the presence of postpartum depression among fathers as well, with a lower cut off score. The traditional cut-off scores for the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale when assessing women is 13 or greater. However, a lower cut-off score above 10 is recommended for fathers as men express emotions differently from women, mainly because they are less expressive with their negative emotions.

It is an acceptable, reliable and valid measure of postpartum depression for both mothers and fathers of newborns and its advantages are that it is open access, it takes only a short time to administer, it is easy to understand, and it is a reasonable tool for screening fathers of newborns for PPPD.

Data quality control

The questionnaire was initially prepared in English. The English version was translated to the Amharic local language and retranslated back to English by a language translator expert to ensure internal consistency. The outcome variable (paternal postpartum depression) was assessed by using the Edinburgh postpartum depression scale with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.87.

Before data collection, training was given to data collectors and supervisor for one day on basic data collection skills by the principal investigator. The training was focused on interview technique, ethical issues, rights of the participants, reading through all the questions and understanding them, and ways of decreasing under/over reporting and maintaining confidentiality.

Follow-up was also performed to them during data collection. Moreover, the questionnaire was pretested on 5%, which was on 32 partners of postpartum women of the sample outside of Dessie town (Hayk town kebeles) before 15 days of the actual data collection time to ensure clarity, wordings and logical sequence of the questions. In addition, the supervisor and principal investigator supervised the whole data collection process and checked the completed questionnaires every day for completeness, and correctness.

Data processing and analysis

Data were cleaned, coded and entered using EpiData version 4.6.0.0 software and the data were crosschecked for completeness before analysis. The entered data were exported and analysed with SPSS version 26. Simple descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentages, mean and Standard Deviations (SD) was computed.

The analysed data were presented using text, tables and figures. Bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between outcome and explanatory variables. Variables with a P value <0.25 in the Bivariable analyses were used as the cut point for eligibility in the multivariable binary logistic regression model.

An effort was made to assess whether the necessary assumptions for the application of multivariable binary logistic regression were fulfilled. The final model goodness-of-fit was cheeked by Hosmer and Lemeshow’s test and the model were fit with a p-value of 0.82. Variables were assessed for multicollinearity, and the data met the assumption of collinearity with a variance inflation factor of 1.11-4.97 and a tolerance test of 0.20-0.89. Finally, statistically significant variables were declared at p value <0.05 and were reserved in the final model with 95% CI.

Results

Paternal factors

In this study, a total of 610 fathers were interviewed with a response rate of 96.2%. The mean age ± SD of the participants was 35.13 ± 6.24 years and the majority of respondents, 323 (53%) were between 25 and 34 years old.

Half of the participants, 309 (50.7%) were Muslim by religion. of the participants, 372 (61%) were urban by residence, and 206 (33.8%) had completed higher education and above. The majority of participants, 444 (72.8%) were employed. Among the employed, 393 (64.4%) were permanent employees, of these 374 (61.3%) received paternal leave.

The average family income of the respondents was 4,260 ± 2,748 Ethiopian Birr, ranging from 1,000 to 24,000 and nearly three-fourths of respondents, 443 (72.6%) were not comfortable by their family income.

The majority of the respondents, 536 (87.9%) had no history of depression, and 80 (13.1%) were using one or more substance (alcohol, chat, cigarette). More than half of the respondents, 341 (55.9%) had experienced of childbirth and almost all of the participants, 589 (96.6%) had only one new-born (Table 1).

| Variables | Frequency (n=610) | Percent (%) |

| Paternal age | ||

| ≤ 25 | 12 | 2 |

| 25-34 | 323 | 53 |

| 35-44 | 228 | 37.4 |

| ≥ 45 | 47 | 7.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 285 | 46.7 |

| Protestant | 13 | 2.1 |

| Muslim | 309 | 50.7 |

| Catholic | 3 | 0.5 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 238 | 39 |

| Urban | 372 | 61 |

| Educational status | ||

| Not read and write | 49 | 8 |

| Read and write | 86 | 14.1 |

| Primary education | 130 | 21.3 |

| Secondary education | 139 | 22.8 |

| Higher education and above | 206 | 33.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 444 | 72.8 |

| Unemployed | 166 | 27.2 |

| Family income | ||

| ≤ 1,500 | 46 | 7.5 |

| 1,501-3,000 | 266 | 43.6 |

| 3,001-5000 | 161 | 26.4 |

| ≥ 5,001 | 137 | 22.5 |

| Comfortable with family income | ||

| Yes | 167 | 27.4 |

| No | 443 | 72.6 |

| Substance use | ||

| Yes | 80 | 13.1 |

| No | 530 | 86.9 |

| History of depression | ||

| Yes | 74 | 12.1 |

| No | 536 | 87.6 |

| Experience of childbirth | ||

| Yes | 341 | 55.9 |

| No | 269 | 44.1 |

| Number of newborn | ||

| One | 589 | 96.6 |

| Twin | 21 | 3.4 |

Table 1: Paternal factors of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Relationship characteristics of the participants

The majority of respondents, 597 (97.9%) were married and almost all of the respondents, 605 (99.2%) had only one wife, 555 (91%) of the respondents responded that they have good marital relationship.

Of the total study participants, 78 (12.8%) had relatives diagnosed with mental illness and received family support and friend support (85.1% and 75.1% respectively) (Table 2).

| Variables | Frequency (n=610) | Percent (%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 597 | 97.9 |

| Single | 5 | 0.8 |

| Divorced | 5 | 0.8 |

| Windowed | 3 | 0.5 |

| Number of wife | ||

| One | 605 | 99.2 |

| More than one | 5 | 0.8 |

| Good marital relationship | ||

| Yes | 547 | 89.7 |

| No | 63 | 10.3 |

| Good parental relationship | ||

| Yes | 568 | 93.1 |

| No | 42 | 6.9 |

| Relatives diagnosed with mental illness | ||

| Yes | 78 | 12.8 |

| No | 532 | 87.2 |

| Family support | ||

| Yes | 519 | 85.1 |

| No | 91 | 14.9 |

| Friend support | ||

| Yes | 458 | 75.1 |

| No | 152 | 24.9 |

| Professional support | ||

| Yes | 446 | 73.1 |

| No | 164 | 26.9 |

Table 2: Relationship factors of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

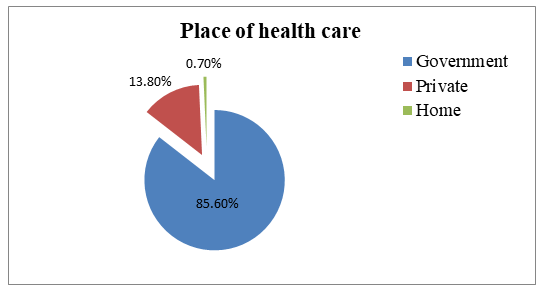

The majority of the respondents’ infants, 522 (85.6%) were delivered at governmental health institutions (Figure 2). Almost more than half of the respondents, 313 (51.3%) were living in their own houses and the majority of the respondents’ wives, 476 (78%) did not go to her mother or family house for delivery.

Figure 2: Place of health care of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Of all respondents’ wives’ pregnancies, 487(79.8%) were planned and 438 (71.8%) and 517 (84.8%) fathers were present at the time of antenatal checkup and delivery of the infant respectively.

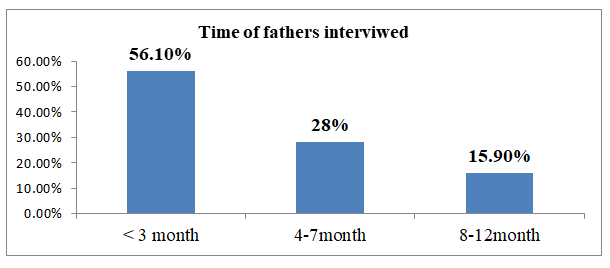

The majority of the respondents’ wives’, 514 (84.3%) reported that the delivery of their child was vaginal delivery and 545 (89.3%) deliveries had full-term of GA. Of all respondents’ infants’, 28 (4.6%) had congenital problems, 93 (15.2%) had sleeping problems (Table 3). More than half of the respondents, 343 (56.2%), the time of the fathers interviewed was <3 months of delivery (Figure 3).

| Variables | Frequency (n=610) | Percent (%) |

| Your housing condition | ||

| Your own | 313 | 51.3 |

| Rental | 297 | 48.7 |

| Did your wives go to her mother or family house | ||

| Yes | 134 | 22 |

| No | 476 | 78 |

| Was the pregnancy planned | ||

| Yes | 487 | 79.8 |

| No | 123 | 20.2 |

| Attend antenatal check up | ||

| Yes | 438 | 71.8 |

| No | 172 | 28.2 |

| Attend delivery of your child | ||

| Yes | 517 | 84.8 |

| No | 93 | 15.2 |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Vaginal delivery | 514 | 84.3 |

| Cesarean section | 96 | 15.7 |

| Gestational age of the pregnancy | ||

| Term | 545 | 89.3 |

| Pre-term | 41 | 6.7 |

| Post-term | 24 | 3.9 |

| Congenital birth problems | ||

| Yes | 28 | 4.6 |

| No | 582 | 95.4 |

| Infant sleeping problem | ||

| Yes | 93 | 15.2 |

| No | 517 | 84.8 |

| Loss of child before this pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 68 | 11.1 |

| No | 542 | 88.9 |

Table 3: Infant and environment related factors of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Figure 3: Time of father interviewed of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Prevalence of paternal postpartum depression

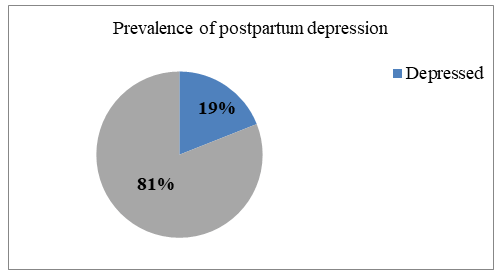

From the overall participants, 116 (19%) (95% CI: 16.0, 22.3) scored above the cut off point for paternal postpartum depression (≥ 10) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Prevalence of paternal postpartum depression among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023.

Factors associated with paternal postpartum depression

In addition to prevalence, this study aimed to identify the factors associated with paternal postpartum depression. A total of 18 variables (residence, employment status, comfortable with family income, substance use, history of depression, number of new-borns, experience of childbirth, relationship with parents, marital status, marital relationship, housing condition, planned pregnancy, ANC check up with your partner, mode of delivery, congenital problem of new-borns, place of child birth, infant sleep problems, and lost child before the birth of this child) were entered to the multivariable binary logistic regression model and analysed by using the entered method.

Only five variables (comfortable with their family income, substance use, experience of childbirth, planned pregnancy and infant sleep problems) were significant variables with paternal postpartum depression.

After adjusting confounding variables, the finding of this study showed that fathers who were not comfortable with their family income were 2.32 times more likely to develop postpartum depression than fathers who were comfortable with their family income (AOR=2.32 (95% CI: 1.16,4.66)).

Those fathers who were currently using one or more substance were 2.48 times more likely to develop postpartum depression than those fathers who were nonusers (AOR=2.48 (95% CI: 1.22, 5.05)).

In addition, experience of childbirth was also affecting the outcome variable (paternal postpartum depression). Those fathers who had experience of child birth nearly two times more likely to be depressed than those fathers who had no experience of childbirth (AOR=1.89 (95% CI: 1.02, 3.50)).

Furthermore, unplanned pregnancy was also an exposure variable that affected paternal postpartum depression. Those fathers whose wives’ had unplanned pregnancy were 2.81 times more likely to develop postpartum depression than those fathers whose wives’ pregnancy was planned (AOR=2.81 (95 % CI: 1.50, 5.25)).

Additionally, infant sleeping problems were a statistically significant independent variable that affected paternal postpartum depression. Those fathers whose infants had sleeping problems were 3.59 times more likely to develop paternal postpartum depression than those fathers whose infants had no sleeping problems (AOR=3.59 (95% CI: 1.80, 7.18)) (Table 4).

|

|

Paternal postpartum depression |

|||

|

Variables |

Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

|

Residence |

||||

|

Rural |

54 (22.7) |

184 (77.3) |

1.47 (0.98, 2.21) |

0.75 (0.43, 1.32) |

|

Urban |

62 (16.7) |

310 (83.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

Employment status |

||||

|

Employed |

70 (15.8) |

374 (84.2) |

1 |

1 |

|

Unemployed |

46 (27.7) |

120 (72.3) |

2.05 (11.34, 3.13) |

1.54 (0.86, 2.75) |

|

Comfortable with family income |

||||

|

Yes |

16 (9.6) |

151 (90.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

No |

100 (22.6) |

343 (77.4) |

2.75 (1.57, 4.82) |

2.32 (1.16,4.66)* |

|

Substance use |

||||

|

Yes |

46 (57.5) |

34 (42.5) |

8.89 (5.34, 14.80) |

2.48 (1.22,5.05)* |

|

No |

70 (13) |

460 (87) |

1 |

1 |

|

Known history of depression |

||||

|

Yes |

27 (36.5) |

47 (63.5) |

2.89 (1.71, 4.88) |

1.12 (0.48, 2.63) |

|

No |

89 (16.6) |

447 (83.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

Number of new-borns |

||||

|

Single |

105 (17.8) |

484 (81.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

Twin |

11 (52.4) |

10 (47.6) |

5.07 (2.10, 12.25) |

1.92 (0.54, 6.82) |

|

Experience of childbirth |

||||

|

Yes |

86 (25) |

255 (75) |

2.69 (1.71, 4.22) |

1.89 (1.02, 3.50)* |

|

No |

30 (11) |

239 (89) |

1 |

1 |

|

Good relationship with your parents |

||||

|

Yes |

105 (18.5) |

463 (81.5) |

1 |

1 |

|

No |

11 (26.2) |

31 (73.8) |

1.57 (0.76, 3.21) |

0.95 (0.35, 2.56) |

|

Marital status |

||||

|

Married |

110 (18.4) |

487 (81.6) |

1 |

1 |

|

Single |

2 (40) |

3 (60) |

2.95 (0.49, 17.88) |

1.46 (0.08, 27.50) |

|

Divorced |

3 (60) |

2 (40) |

6.64 (1.09, 40.22) |

2.47 (0.10, 2.00) |

|

Windowed |

1 (33.3) |

2 (66.7) |

2.21 (0.20, 24.63) |

0.47 (0.13, 17.11) |

|

Good marital relationship |

||||

|

Yes |

91 (16.6) |

456 (83.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

No |

25 (39.7) |

38 (60.3) |

3.30 (1.90, 5.73) |

1.71 (0.76, 3.89) |

|

Housing condition |

||||

|

Your own |

41 (13) |

272 (87) |

1 |

1 |

|

Rental |

75 (25) |

222 (75) |

2.24 (1.47, 3.41) |

1.45 (0.84, 2.50) |

|

Planned pregnancy |

||||

|

Yes |

54 (11) |

433 (89) |

1 |

1 |

|

No |

62 (50.4) |

61 (49.6) |

8.15 (5.18, 12.82) |

2.81 (1.50, 5.25)* |

|

Did you attend ANC |

||||

|

Yes |

49 (11) |

389 (89) |

1 |

1 |

|

No |

67 (39) |

105 (61) |

5.07 (3.31, 7.76) |

1.55 (0.85, 2.86) |

|

Mod of delivery |

||||

|

Vaginal delivery |

83 (16) |

431 (84) |

1 |

1 |

|

Cesarean section |

33 (34) |

63 (66) |

2.72 (1.68, 4.41) |

1.52 (0.77, 3.01) |

|

Congenital birth problems |

||||

|

Yes |

21 (75) |

7 (25) |

15.38 (6.36, 37.20) |

2.58 (0.80, 8.31) |

|

No |

95 (16) |

487 (84) |

1 |

1 |

|

Place of health care |

||||

|

Government |

91 (17) |

431 (83) |

1 |

1 |

|

Private |

23 (27) |

61 (73) |

1.79 (1.05, 3.04) |

1.03 (0.49, 2.15) |

|

Home |

2 (50) |

2 (50) |

4.74 (0.66, 34.06) |

5.10 (0.46, 56.69) |

|

Infant sleeping problems |

||||

|

Yes |

55 (59) |

38 (41) |

10.82 (6.61, 17.70) |

3.59 (1.80,7.18)* |

|

No |

61 (12) |

456 (88) |

1 |

1 |

|

Lost child before this child |

||||

|

Yes |

40 (58.8) |

28 (41.2) |

0.11 (0.07, 0.20) |

2.20 (0.99, 4.89) |

|

No |

76 (14) |

466 (86) |

1 |

1 |

|

Note: *statistically significant at 95% CI, P<0.05 with paternal postpartum depression, CI: Confidence Interval; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; COR: Crude Odds Ratio, 1= reference |

||||

Table 4: Bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analysis of paternal postpartum depression and associated factors among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023 (N=610).

Discussion

The findings of the current study showed the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression and associated factors among partners of women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023. The factors that were significantly associated with paternal postpartum depression were not comfortable with their family income, substance use, experience of childbirth, unplanned pregnancy and infant sleep problems.

In this study, 116 (19%) (95% CI: 16.0, 22.3) partners had postpartum depression. This finding is in line with the studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Sweden, China and Japan, where the prevalence of paternal postnatal depression were 16.6%, 21%, 20.4% and 17% respectively. The reason for this consistency might be due to similarity in the assessment tool (EDPS).

On the other hand, this prevalence of paternal postpartum depression was lower than the studies conducted in Pakistan, in 2020 and 2022, Ireland and Italy, where the prevalence of paternal postnatal depression was 28.3%, 23.5%, 28% and 28% respectively. The possible explanation for this discrepancy in prevalence of paternal postnatal depression may be due to the socio-demographic differences, sample size and study setting differences.

However, the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression in this study was higher than others studies conducted in the UK, in 2016, Germany, in 2020, Hong Kong, China, in 2014, Japan, in 2017, Iran, in 2018, Poland, in 2021, Ireland, Japan, in 2015 and Nigeria, the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression were 3.6%, 5%, 5.2%, 8.8%, 11.7%, 13%, 12%, 13.6% and 8.9% respectively.

The possible explanation for this discrepancy might be due to the socio-demographic differences, sample size differences, different methodological approaches, different assessment tools for screening depression and cut point difference, and the timing of depression assessment (early postpartum vs. late postpartum). For example, the studies conducted in the UK, in 2016 and in Germany, in 2020 used a longitudinal cohort study method. The Kessler 6 (K6) scale was used as an indicator of current depressive symptoms in the UK and the cut off point for the risk of paternal depression in Iran, in 2018, and Ireland, was an EPDS score ≥ 12.

In the current research, among the paternal factors, fathers who were not comfortable with family income were more likely to develop odds of PPPD than those who were comfortable with their family income (AOR=2.32 (95% CI: (1.16, 4.66)).

Fathers who self-reported that they were struggling to survive financially and living in poor economic circumstances had a greater risk of PPPD as compared to those fathers who were financially comfortable. This finding was consistent with a study performed in Ireland, Japan, in 2015 and Poland.

It might be the reason that becoming a parent increases the need to fulfill the materials for the family including the new-born basic needs or facilities, due to this difficulty in economic conditions that might further affect the mood status of the fathers and might cause them to develop depression during this period. Additionally, it might be because in many societies, the main man’s duty is to guarantee the family’s financial security. After the birth of the child, due to the increased financial burden on the family, more emphasis was placed on the breadwinning role of the fathers, and they had less opportunity to perform parental duties. This might further cause them to develop PPPD.

This result is inconsistent with the study conducted in Japan, in 2016, in which the father’s household income issues were not significantly associated with PPPD. This might be due to the socio demographic differences and study setting.

In the current research, fathers who were currently using substances were more likely to develop odds of paternal postnatal depression than fathers who were nonusers (AOR=2.48 (95% CI: 1.22, 5.05)). This finding was in line with studies conducted in Brazil and in Tampere, Finland, 2013. This might be because taking any substance during the postpartum period might change the mood status of the fathers, intensify negative emotion and further cause them to develop depression during the postpartum period.

Additionally, the use of any substance might negatively affect the quality of sleep. This sleep disturbance was also found to be a cause of paternal postnatal depression, as evidenced by research conducted in Pakistan, in 2022, because good quality sleep restores our body and minds and is vital to mental health. Moreover, the use of any substance might also cause them to experience a financial crisis and eventually result in PPPD.

Furthermore, those who had experience of childbirth were more likely to develop odds of paternal postpartum depression those who were first time fathers (AOR=1.89 (95% CI: 1.02, 3.50)). This result was in line with the studies conducted in Iran, 2021, Tampere, Finland, 2013 and Iran, 2017. The reason may be that fathers’ mental health condition deteriorates due to facing the challenge of parenting and money-related worries become the reason for men’s unhappiness. Additionally, the birth of an additional child is an added responsibility of fathers for caregiving, nurturance and financial support.

In addition, this result is also consistent with a study conducted in Sweden, in 2021. This might be evidenced by this Sweden study that multiparous fathers received significantly less professional and social support and were less frequently invited to child health visits than primiparous fathers, and those fathers reported only fewer depressive symptoms when they received professional support from the prenatal midwife, nurse team, and child health nurse as well as social support from their partner. Eventually, multiparous fathers indirectly affected paternal postpartum depression more than primiparous fathers.

Additionally, it might be that having more children imposes a greater burden on parents in terms of both responsibility and costs, which can cause PPPD, especially in countries such as Ethiopia, which are experiencing more economic crises and high inflation rates.

On the other hand, it was not statistically significantly associated with paternal postpartum depression in studies conducted in Japan, in 2015 and in Pakistan, in 2022. This might be due to differences in the sample size, and socio-demographic factors.

Interestingly, these results are contrary to a study conducted in Canada, in 2021, in which fathers who had sleep disturbances caused by different exposures were risk factors for paternal postnatal depression, and first-time fathers were more likely to suffer from depression due to sleep disturbances in the postnatal period than fathers who had experience of childbirth.

Additionally, a study conducted in Sweden, the findings of study indicated that fathers who have their first child may had similar ideals for parenthood, this lack of preconditions may have increased their feelings of inadequacy and experience the responsibility for a new family as more troublesome and negative effects of paternal depression on parenting behavior than fathers who had experience of childbirth. This might be due to socio-demographic differences, study method and study setting.

In the present study, fathers who had unplanned pregnancies were more likely to develop odds of paternal postpartum depression than fathers who had planned pregnancies (AOR=2.81 (95% CI: 1.50, 5.25)). Assuming that these variables are stressors, anxiety, and worry about the outcome of this unplanned pregnancy, they can be effective in causing depression after childbirth. This result was consistent with the study conducted in Iran, in 2021. The results suggested that unplanned pregnancy had a direct and significant effect on PPPD. This might be the reason for the similarity in the assessment tool.

Contrary to investigations conducted in Saudi Arabia, Japan, in 2015, Ireland and Iran, in 2017, there was no significant association between unplanned pregnancy and paternal postpartum depression. The possible explanation for this discrepancy might be due to socio demographic differences, differences in study periods, study methods and study settings.

Another significant variable found in the current study was having an infant with sleeping problems. Fathers who had an infant with sleeping problems were more likely to develop odds of paternal postpartum depression than fathers who had no infant sleeping problems (AOR=3.59 (95% CI: 1.80, 7.18)). This result was congruent with a study conducted in Ireland. These results might be due to the healthiness of the child related worries, stress and anxiety becoming the reason for deteriorating fathers’ mental health conditions and further causing them to develop paternal postpartum depression.

Conclusion

Based on the present study, almost one fifth of fathers had paternal postpartum depression. Paternal factors such as; not comfortable with their family income, substance use and fathers experience of childbirth, and environment and infant factors such as; unplanned pregnancy and infant sleeping problems were significant factors of paternal postnatal depression in this study area.

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations were forwarded to the Dessie town health department, health professionals, different NGOs and researchers working in health and other sectors.

The Dessie town health department recommended collaborating with the FMOH and other responsible sectors to design policies and programs to aid men in the transition period to parenthood such as paternal leave policy while maintaining their livelihood and mental health and developing guidelines for postpartum follow-up that better to integrated with mental and reproductive health screening for both partners.

The Dessie town administration also recommended to offer basic health facilities that are needed for parents and their childcare with acceptable costs during the postpartum period. Additionally, it is recommended to provide further health education on the effects of substance use by using different mass media.

NGOS in collaboration with other sectors working on Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) are better to provide further attention to the utilization of family planning to minimize unplanned pregnancy and support better to offer to multiparous fathers. Additionally, it is better to provide training for health care providers regarding paternal postpartum depression and related mental issues.

Health care professionals are recommended to provide mental health screening for fathers during the postpartum period. The significant predictors better to considered especially fathers who had economic problems, substance users, unplanned deliveries, fathers who had experience of birth and infant sleeping problems, and incorporated into the clinical assessment and intervention of paternal PPD.

It is recommended that researchers conduct further research by using different designs (longitudinal, mixed study), and settings and identify further potentially important unmeasured predictors of PPPD.

Strength and Limitation of Study

This is the first study to be carried out in the study area and in the Northern region of Ethiopia. This study was unique as it attempted to analyze different predictors of paternal postpartum depressive symptoms, acknowledging the existence of this mental health issue in men and adding to our limited knowledge of this problem in Ethiopia.

Additionally, this study was a community-based survey designed to explore different exposures that can predict the depression of fathers by focusing on fathers who cannot visit health institutions for different reasons. Despite this strength, the study has some limitations.

It is difficult to make comparisons in prevalence and associated factors of paternal postnatal depression, due to the limited number of studies on related topics, especially in developing countries, including Ethiopia.

Furthermore, the assessment of depression symptoms was based on self-report measures, and depression symptoms may have a high possibility of underreporting due to social desirability. This is a pertinent issue because the tendency for a significant underreporting rate of depression in men is high.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ethical Review Committee (ERC) with the approval number (CMHS/840/20/15). A formal letter for permission and support was written to the zonal health department of Dessie from Wollo University, official permission to conduct the study was obtained.

The respondents were informed about the objective, purpose, and benefits of the study and the right to refuse to participate, and then informed written and signed consent was obtained. Moreover, the confidentiality of information was guaranteed by using code numbers rather than personal identifiers and by keeping the data locked.

Availability of Data and Material

All related data has been presented within the manuscript. The data set supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the authors on request.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that no one has competing interests.

Author Contribution

AA conceived the study and undertook the statistical analysis. AA and AW supervised the study design and statistical analysis. AA, MA and AB contributed to the writing of the manuscript and all authors read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Wollo University for approval of ethical clearance, technical and financial support of this study. Then, we would like to thank all study participants who participated in this study for their commitment to responding to our interviews and observations. Lastly, we are indebted to each department's health offices for their assistance and permission to undertake the research.

Tel: XXXXXXX

E-mail: XXXXXXXX

Received: April 06, 2020 Accepted: April 17, 2020 Published: May 04, 2020

Citation: XXXXXXXXXXXX.

XXXXXXXXXXX

References

- Musser AK, Ahmed AH, Foli KJ, Coddington JA (2013) Paternal postpartum depression: What health care providers should know. J Pediatr Health Care 27: 479–485.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Philpott LF (2016) Paternal postnatal depression: How midwives can support families. Br J Midwifery 24: 470–476.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) DSM–5 Manual. Am Psychiatr Assoc 9.

- Biebel K, Alikhan S (2016) Paternal postpartum depression (English and Spanish versions). J Parent Fam Ment Health 1: 1-4.

- Glasser S, Lerner-Geva L (2019) Focus on fathers: paternal depression in the perinatal period. Perspect Public Health 139: 195–198.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yazdanpanahi Z, Mirmolaei ST, Taghizadeh Z (2021) Relationship between paternal postnatal depression and its predictors factors among Iranian fathers. Rev Psiquiatr Clin 48: 162–167.

- Wang D, Li YL, Qiu D, Xiao SY (2021) Factors influencing paternal postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 293: 51–63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holopainen A, Hakulinen T (2019) New parent’s experiences of postpartum depression: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 17: 1731-1769.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noorullah A, Mohsin Z, Munir T, Nasir R, Malik M (2020) Prevalence of paternal postpartum depression. PJNS 15: 11-16. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaheen NA, AlAtiq Y, Thomas A, Alanazi HA, AlZahrani ZE, et al. (2019) Paternal postnatal depression among fathers of newborn in Saudi Arabia. Am J Mens Health 13.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayinde O, Lasebikan VO (2019) Factors associated with paternal perinatal depression in fathers of newborns in Nigeria. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 40: 57–65.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom M (2013) Depressive symptoms in new firstâ?ÂÂtime fathers: Associations with age, sociodemographic characteristics, and antenatal psychological wellâ?ÂÂbeing. Birth 40: 32-38.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weitzman M, Rosenthal DG, Liu Y (2011) Paternal depressive symptoms and child behavioral or emotional problems in the United States. Pediatrics 128: 1126-1134.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamalifard M, Payan SB, Panahi S, Hasanpoor S, Kheiroddin JB (2018) Paternal postpartum depression and its relationship with maternal postpartum depression. J Holist Nurs Midwifery 28: 115–120.

- Walsh TB, Davis RN, Garfield C (2020) A call to action: Screening fathers for perinatal depression. Pediatrics 145.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nishimura A, Fujita Y, Katsuta M, Ishihara A, Ohashi K (2015) Paternal postnatal depression in Japan: An investigation of correlated factors including relationship with a partner. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15: 1–8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mcallister F, Burgees A, Kato J, Barker G (2012) Fatherhood: Parenting programmes and policy-a critical review of best practice. 89.

- Barry KM, Gomajee R, Benarous X, Dufourg M, Courtin E, et al. (2023) Paternity leave uptake and parental post-partum depression: Findings from the ELFE cohort study. The Lancet Public Health 8: e15-e27.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi