Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 11 Issue: 2

Stigma: A Barrier Created by Limited Access to Care and Health Education on Hepatitis C (HCV) Testing and Treatment within the Puerto Rican Population

Lisa Ruiz-Casprowitz*

Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Touro University, New York, NY 10036, United States

*Corresponding Author: Lisa Ruiz-Casprowitz

Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Touro University, New York, NY 10036, United States

E-mail:lisacaspro@gmail.com

Received date: 01 July, 2024, Manuscript No. IJMHP-24-142430; Editor assigned date: 04 July, 2024, PreQC No. IJMHP-24-142430 (PQ); Reviewed date: 19 July, 2024, QC No. IJMHP-24-142430; Revised date: 10 June, 2025, Manuscript No. IJMHP-24-142430 (R); Published date: 17 June, 2025, DOI: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000290.

Citation: Ruiz-Casprowitz L (2025) Stigma: A Barrier Created by Limited Access to Care and Health Education on Hepatitis C (HCV) Testing and Treatment within the Puerto Rican Population. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 11:2.

Abstract

Significance: Hepatitis C (HCV) is a long-term illness that progresses gradually and has become increasingly common among People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico. Barriers such as inadequate access to healthcare and limited health education contribute to widespread stigma against both HCV and the PWID community.

Purpose: This review aims to explore the existing evidence on how stigma related to Hepatitis C negatively influences testing and treatment among PWIDs in Puerto Rico. It also emphasizes the urgent need for federal support and funding to implement prevention and treatment initiatives targeting this stigma.

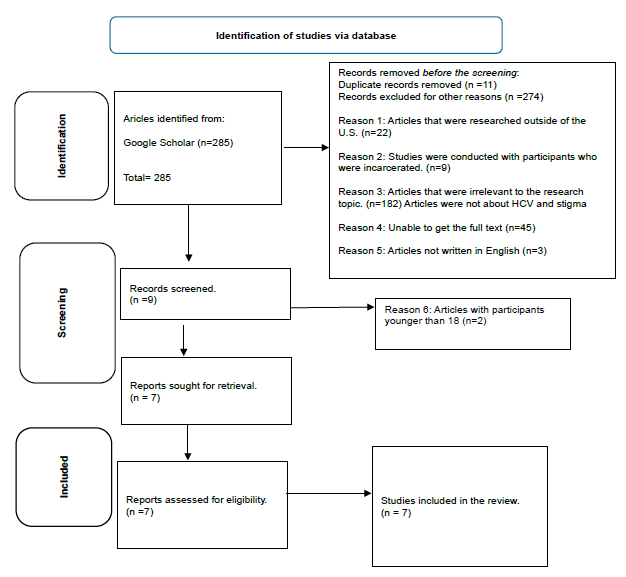

Methodology and scope: This systematic review did not involve any participants. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework guided the literature review process. A total of 285 articles were initially identified through a targeted keyword search, including terms like "Puerto Ricans," "Chronic Hepatitis," "Hepatitis C," "HCV stigma," and related topics. After removing 11 duplicates and excluding 274 articles based on various criteria such as geographic relevance, study population, and language only 7 articles met the inclusion criteria for review.

Key findings: Stigmatization related to HCV significantly affects PWIDs’ willingness to undergo testing and pursue treatment, thereby impacting timely diagnosis and healthcare outcomes in Puerto Rico. The literature suggests that stigma acts as a critical barrier, deterring individuals from accessing essential medical services.

Results: Out of 285 initial sources, a rigorous screening process led to the selection of 7 articles suitable for review. Reasons for exclusion included non-U.S. based studies, incarcerated populations, lack of relevance, unavailability of full texts, and studies involving minors.

Conclusion: This review highlights a pressing public health issue: persistent stigma surrounding HCV and drug use among PWIDs, coupled with limited healthcare access and health literacy, continues to hinder effective intervention in Puerto Rico. According to data presented by Watson (2022), approximately 95% of those diagnosed with HCV report having faced stigma at some point in their lives. To curb the spread of HCV and mitigate stigma, it is vital for the U.S. government to allocate resources for public education, expand access to testing and treatment, and support community-level programs. Collaborative efforts among policymakers, medical professionals, and local organizations are essential to improve healthcare infrastructure and deliver equitable care to vulnerable populations.

Keywords: HCV; PWIDs; Populations; Symptoms

Introduction

Viral hepatitis remains a significant public health concern in the United States, with the primary culprits being Hepatitis A, B, and C [1]. These viruses are all capable of causing acute liver inflammation and, in severe cases, chronic liver disease [2]. Hepatitis C (HCV), in particular, has earned the nickname “the silent killer” due to its tendency to remain asymptomatic for many years, often until irreversible liver damage has occurred. Without timely diagnosis and treatment, HCV can lead to liver cirrhosis, liver failure, and even death [3].

Symptoms of HCV infection vary widely, ranging from minor discomfort to life-threatening complications. Many individuals remain unaware of their infection until advanced liver damage is evident. HCV transmission can occur through various means, including medical procedures performed in countries with inadequate infection control, unregulated body piercings or tattoos, dental work, organ transplants, childbirth, sexual contact with an infected partner, and blood transfusions. However, intravenous drug use remains the most common transmission route [4]. Because HCV is transmitted through blood-to-blood contact, People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) are at especially high risk. Early screening and treatment are essential to improving health outcomes [5].

Impact of stigma on individuals living with HCV

Hepatitis C is often associated with socially stigmatized behaviors, such as injection drug use. As a result, individuals diagnosed with HCV may face judgment and discrimination, which can negatively influence their emotional well-being and access to care. These stigmatizing attitudes foster isolation, both self-imposed and from social networks, and can affect employment opportunities and medical treatment [6].

Research by Lekas et al., revealed that many individuals perceive HCV as a highly contagious disease, even when it is not transmitted through casual contact. These misconceptions fuel fear and alienation, leading to self-stigma and social withdrawal. The study highlighted the significant impact of stigma on the behavior and mental health of those living with HCV.

Stigma within the healthcare system

Stigmatization in healthcare settings presents a serious barrier to effective treatment and disease management. Stigma can influence the way medical professionals view and treat individuals with HCV, particularly those with a history of injection drug use. This judgment can manifest in the form of neglect, avoidance, or unequal treatment, further marginalizing an already vulnerable population [7].

A study by Hernández et al., identified increased rates of HCV and HIV among PWIDs in Puerto Rico, attributing these outcomes to both individual behaviors and broader social factors, including systemic stigma. Healthcare providers’ biased attitudes toward chronic conditions such as HCV can discourage patients from seeking or continuing treatment.

Building trusting relationships between healthcare professionals and HCV-positive individuals is crucial for overcoming stigma. Engaging patients as active participants in their care and addressing the social context of their illness can help mitigate the negative effects of stigmatization [8].

Hepatitis C in Puerto Rico

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection rates among People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico are alarmingly high. Research conducted at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City found that HCV prevalence among Puerto Rican PWIDs born on the island (86%) is significantly higher than among those born in the mainland U.S.(70%) [9]. Contributing factors include limited access to substance use treatment programs and a lack of comprehensive HCV-related healthcare services.

In 2023, the estimated HCV prevalence in Puerto Rico ranged from 76.5% to 78.4%, with PWIDs comprising the majority of affected individuals. Contributing to this crisis are low diagnosis rates, minimal treatment access, inadequate referrals, and negative encounters with healthcare providers. These factors create substantial barriers for those most in need of care.

A study by Silvia-Diaz et al., confirmed that Puerto Ricans suffer from poorer health outcomes compared to both non-Hispanic and other Hispanic populations in the U.S., highlighting widespread healthcare disparities. Similarly, research by Perez, et al., found elevated HCV rates among high-risk groups in San Juan, Puerto Rico, urging further investigation into the behaviors and environmental factors contributing to the spread. This growing public health concern underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive HCV prevention and treatment strategy tailored to Puerto Rico’s specific challenges.

Medicaid barriers to HCV treatment

Despite global recognition of HCV as a critical health issue, Puerto Rico has historically relied on punitive policies in addressing it. Between 1998 and 2002, under the guise of health reform, the Puerto Rican government reduced drug treatment options for PWIDs by 41%, effectively limiting their access to care [10].

By 2014, Medicaid policies further restricted HCV treatment eligibility. Patients were required to meet strict criteria, including proof of advanced liver damage, documentation of sobriety, and consultation with a specialist. Access to medication was limited to those deemed the most severely ill, due to the high cost of HCV drugs. Pre-authorization protocols and narrow prescribing privileges created significant delays in diagnosis and treatment for many high-risk individuals. These discriminatory restrictions disproportionately affected Puerto Rican PWIDs, leaving many undiagnosed and untreated.

The role of HCV education in reducing stigma

A lack of public understanding about how HCV is transmitted contributes significantly to stigma and discrimination. Study participants often described the general population’s awareness of the virus as “ignorant” or “uneducated,” pointing to widespread misinformation. A study by Soto-Salgado, et al., involving Puerto Ricans aged 21–64 in both New York City and Puerto Rico, found that a large portion of the participants lacked basic knowledge about HCV transmission and risk factors.

Comprehensive, evidence-based public health education is essential in dispelling these myths. Anti-stigma campaigns that address misconceptions can reduce public fear and discrimination while encouraging early diagnosis and treatment. Educational efforts during the Interferon treatment era demonstrated significant improvements in patient outcomes by raising awareness, enhancing care coordination, and promoting treatment adherence. Moving forward, similar interventions are crucial for reducing the HCV burden among vulnerable populations in Puerto Rico.

Problem statement and research question

People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico face significant challenges when it comes to accessing Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) care and health education. These limitations contribute to widespread stigma, which, in turn, discourages testing and delays treatment, ultimately worsening health outcomes. The purpose of this review is to explore how the intersection of limited healthcare access and insufficient HCV education perpetuates stigma and impacts the healthcare-seeking behaviors of PWIDs.

Research question

Does restricted access to HCV healthcare services and inadequate health education contribute to stigma that prevents PWIDs in Puerto Rico from pursuing HCV testing and treatment?

Materials and Methods

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review focused on literature exploring the relationship between HCV-related stigma and healthcare access among PWIDs in Puerto Rico. To be eligible for inclusion, articles had to meet the following criteria:

Discuss the relationship between HCV, stigma, and healthcare in the context of Puerto Rico include participants aged 18–64, include both male and female participants. Exclude studies involving incarcerated individuals, be published in English, be based on U.S.- based research, with a particular focus on Puerto Rico. Provide data related to PWIDs and HCV stigma.

Due to the abundance of literature on HCV, the review was limited to studies that strictly met the above criteria in terms of topic relevance, geographic focus, participant demographics, and language.

Information sources

The review utilized Google Scholar to identify peer-reviewed articles and academic journals relevant to HCV, stigma, and PWIDs in Puerto Rico. The search strategy was built around specific keywords, including: Puerto Ricans, chronic hepatitis, Hepatitis C, Hispanic population, HCV stigma in healthcare, and HCV education. Only articles based on credible, evidence-based research were selected. Each source underwent a thorough evaluation to ensure its scientific validity and relevance to the research question (Table 1).

| Publication | Author (s) | Data of search and database |

| Hepatitis C virus care cascade among people who inject drugs in Puerto Rico: Minimal HCV treatment and substantial barriers to HCV care | Pedro Mateu- Gelabert | Date of search: September 12, 2023 Database: Google scholar |

| Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it | Nyblade L | Date searched: May 14, 2022 Database: Google scholar |

| Understanding Barriers to Hepatitis C virus care and stigmatization from a social perspective | Treloar C | Date of search: May 14, 2022 Database: Google scholar |

| When "the Cure" is the risk: Understanding How substance use affects HIV and HCV in a layered risk environment in San Juan, Puerto Rico | Hernández D | Date of search: May 14,2022 Database: Google scholar |

| Hepatitis C, stigma, and cure | Marinho, | Date of Search: May 20,2022 Database: Google scholar |

Table 1: Information source chart.

Search strategy

An extensive literature search was carried out using Google Scholar to identify studies focused on stigma related to Hepatitis C (HCV), particularly within the Puerto Rican and broader Hispanic communities. Key terms included: stigma, HCV stigma, Hepatitis C, Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican, access to healthcare, healthcare disparities, HCV-related health education, and stigma in healthcare settings. The search returned 285 results. Studies were considered for inclusion if they involved individuals or populations who were People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs), had been diagnosed with HCV, and had encountered stigma due to their condition. Only research providing data on prevalence and incidence was selected for detailed review.

Selection process

A single reviewer independently screened and evaluated the studies based on relevance and quality. Priority was given to those exploring HCV-related stigma, healthcare access issues, and health education efforts within the Puerto Rican population, including both urban and rural contexts. The inclusion criteria were limited to English-language publications, adult participants aged 18–64, and studies conducted in the United States and Puerto Rico. Exclusion criteria included studies involving incarcerated individuals, non-relevant topics, and articles without full-text availability. After applying these filters, seven studies were deemed suitable for inclusion in the analysis.

Data collection process

Information was extracted from each selected article, including author names, publication year, and applicable guidelines or frameworks referenced. Data points collected included historical and current statistics on HCV prevalence among the Puerto Rican population, especially among PWIDs, as well as levels of HCV awareness within these groups. Additional information on frequency, duration, sample characteristics, and qualifications was also compiled. This data was critically analyzed to support the research objectives and formulate evidence-based conclusions.

Risk of bias assessment

The seven studies selected for this review underwent detailed evaluation by multiple reviewers, who extracted data using a range of participant-focused and literature-based methods, as outlined in Table 2. Each study prioritized objectivity and critically analyzed evidence related to HCV and stigma. Diverse survey techniques were applied to minimize bias, and no participants were subjected to harm or undue risk during the studies. The findings from these studies were consistent with previous systematic reviews, with no contradictory or unexpected results reported.

Data items

| Author and date | Themes | Summary of studies |

| P Mateu-Gelabert | Lack of HCV information, Lack of access to HCV care, Negative interactions and stigma felt by medical providers, Stigma felt by individuals with HCV. | Participants in Puerto Rico were asked questions on factors that would prevent them from getting treated for HCV. Participants. Felt unwelcome at medical facilities due to their HCV status and felt stigmatized. Felt stigma affects their decision to get treated. Had lack of awareness and accessibility to HCV information and services and treatment restrictions. |

| Hernández D | Lack of HCV education and treatment services Lack of HCV medical care access Puerto Rican IDU’s feeling of stigma felt by healthcare professionals. |

The research concluded that IDUs in Puerto Rico experience. Various issues that affect linkage to HCV care treatment, Stigma that impedes treatment and testing, Stigma felt by medical professionals creates a reluctance to disclose the status, Lack of HCV education and medical and treatment services increases HCV rates and creates stigma. |

| Treloar | Stigma felt by healthcare professionals. Stigma impacts the decision to get treatment. Individual feelings on stigma Stigma creates a barrier between individuals and medical providers. |

The study brings to awareness on how Stigma impacts decision-making for treatment and when to engage. The disconnect between the personal experience of HCV and the assumptions of medical providers affects treatment. Healthcare settings are where individuals most report to have experienced stigma. Education on HCV awareness is needed. |

| Varas-DÃaz | Stigmas affect the quality of life. Health professionals’ negative attitudes and stigma affect HCV treatment. Denial of the basic standards of care to specific populations (IDUs) Stigma influences the decision to get treated. |

The qualitative results revealed Puerto Rican healthcare professionals in training had stigmatizing attitudes toward illicit drug users. HCV education is needed to provide awareness. Stigma impacts the treatment of those with HCV. |

| Nyblade | The research examined how stigma in healthcare facilities can contribute to Not seek treatment due to stigma. The lack of knowledge regarding certain conditions Disclosing stigmatizing status |

The findings showed Stigma in health facilities is evident. Stigma negatively impacts patients’ health and eagerness to seek treatment. Disclose their health status due to fear of being stigmatized by health professionals. Medical professionals have stigmatizing views towards certain conditions. Stigma interventions are needed to reduce stigma. |

| Marinho RT | HCV impacts socialization and quality of life. HCV Stigma is associated with anxiety and fear of transmission. Stigma causes social isolation. Stigma affects diagnosis and treatment. Lack of adequate HCV information creates stigma among health professionals |

Marinho researched on how Stigma impacts how the virus is viewed. Stigma influences the decision not to seek testing and treatment. Stigma affects a person throughout HCV. Healthcare professionals’ perception of HCV might influence the treatment of HCV patients. |

| Lekas HM | HCV as an added layer to HIV was more stigmatizing than HIV alone or both. How felt stigma from health care providers is due to a lack of understanding of behaviors among IDUs and HCV as a disease Experiences of felt and enacted stigma among former and current IDUs |

The study examined Which of the two conditions (HIV/HCV) were stigmatized the most Participants’ perceptions of their statuses. Stigma felt by participants among their peers, family, and medical professionals. Lack of knowledge of HCV creates negative perceptions and stigma. |

Table 2: Lists the author, common themes, and the summary of each study.

Evaluation of effectiveness

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework was used to guide the selection and evaluation process. Each article was reviewed for methodological soundness, including clearly defined study design, variables,demographic details, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. To assess effectiveness, the authors employed both qualitative and quantitative approaches, ensuring an objective understanding of each study’s findings. Population data were analyzed through both input and output metrics, and all research measures were reviewed for precision and consistency.

Methods of data synthesis

The synthesis process began by compiling essential details publication year, author(s), data collection methods, and study titles into a structured Excel sheet. Duplicates, incomplete texts, and irrelevant articles were removed to maintain data integrity. The remaining studies, once confirmed relevant, spanned a wide range of research designs including observational studies, interventional trials, systematic reviews, respondent-driven sampling, non-randomized controlled trials, before-and-after studies, case series, and individual case reports. Additionally, qualitative methodologies such as ethnography and content analysis were incorporated. Only Englishlanguage titles and abstracts were retained to ensure uniformity across the dataset.

Assessment of reporting bias

Each included study was critically reviewed to ensure relevance and credibility. A focused search was performed on Google Scholar using targeted keywords such as: Puerto Ricans, Chronic Hepatitis, Hispanic population, Hepatitis C, Puerto Rico, Stigma, HCV stigma in healthcare, and HCV education. The evaluation process emphasized details like publication year, participant demographics, and geographic focus, ensuring that only studies meeting the review criteria were analyzed. This rigorous approach minimized potential reporting bias, enhancing the trustworthiness of the findings.

Certainty of evidence

The PRISMA method guided the comprehensive screening and selection of studies, ensuring a transparent and consistent process. Non-English studies, duplicates, and incomplete records were excluded. The final selection of evidence was cross-verified with authoritative sources to confirm the reliability of the data. This critical appraisal ensured that the findings were grounded in high-quality, evidence-based research, free from misleading or unsupported claims.

Results

Study selection

A total of 285 articles were initially identified through a targeted Google Scholar search using specific keywords, including: Puerto Ricans, Chronic Hepatitis, Hispanic population, Hepatitis C, Puerto Rico, Stigma, HCV stigma in healthcare, and HCV education. Each article’s title, abstract, and introduction were thoroughly screened to determine its relevance to the research focus. This systematic review process ensured that only studies closely aligned with the topic were included (Table 3). The careful selection of credible and relevant sources was aimed at producing accurate and meaningful insights. A detailed overview of the study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

| Author and date | Age | Genders | Region | Populations |

| P Mateu Gelabert | 21 years old> | Both genders | Puerto rico | 150 Puerto Rican participants with positive HCV status and previous or current injection drug users who are disproportionately affected by HCV and access to care. 87% HCV Ab positive 72% were RNA positive 48% were linked to care, 32% were already in treatment 58% completed treatment 71% were cured |

| Hernández D | 24-55 years of age |

Both genders | San Juan, Puerto Rico | 150 Puerto Rican participants who were PWIDs and have or are at risk for HIV/HCV who have experienced challenges in linkages to care and retention in care. |

| Varas-DÃaz, N | 21 years and older | Both genders | Various hospitals and universities throughout Puerto Rico |

501 participants were healthcare professionals from multidisciplinary teams in Puerto Rico. |

| Trelaor C | 21 years and older | Both gender | Global | The general population with HCV has experienced stigma from medical providers |

| Lekas M | 20-69 | Both genders | New York City and Puerto Rico | 132 participant’s HIV/HCV-coinfected men (69%) and women (31%) U.S. born Puerto Ricans and Puerto Ricans born on the island. Who have experienced multiple layers of stigmatization due to coinfection. |

| Nyblade L | 21 and older | Both genders. | Global- United States, Canada, and Ghana |

Healthcare providers and patients who have various chronic conditions |

| Marinho RT | No age range was mentioned. | Both genders | Globally | General population with HCV positive status |

Table 3: Study characteristics.

Figure 1: Study selection flow chart.

Results of individual studies

Table 4 depicts the results for each study. The extracted data from each article included the author, title, study aims, data collection methods, study type, and conclusion.

| Title | Author | Research methods |

Study type |

Study aims |

Conclusion |

| Hepatitis C virus care cascade among people who inject drugs in Puerto Rico: Minimal HCV treatment and substantial barriers to HCV care | Mateu- Gelabert P | Respondent-driven sampling method referral sampling |

Quantitative/ Qualitative |

The goal of the study was to describe the HCV cascade of care among IDUs in Puerto Rico, and to identify gaps and barriers to HCV care. With stigma and perceptions presenting as a barrier to HCV care. |

The study identified HCV barriers that included lack of HCV testing, linkage to care, knowledge of treatment and testing, and treatment restrictions. Other barriers included transportation, drug abstinence, and stigma. |

| Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it | Nyblade L | The study used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. |

Systematic review |

The research assessed the impact of stigma in healthcare and how interventions to reduce stigma in health facilities and address multiple stigmatized health conditions. |

The study concluded that stigma in health facilities affects treatment decisions and health outcomes. |

| Understanding Barriers to Hepatitis C Virus care and stigmatization from a social perspective | Treloar C | An online search strategy was conducted using databases such as: Google Scholar WorldCat PubMed CrossRef |

Literature review |

The review wanted to raise awareness and understanding of stigma and its role in individuals’ decisions on “if and how” to engage in HCV care. |

The study concluded that stigma directly influences mental and physical health outcomes and the decision to seek testing and treatment. |

| Understanding How Substance Use Affects HIV and HCV in a Layered Risk Environment in San Juan, Puerto Rico | Hernánde z D | Rapid ethnographic assessment |

Quantitative/ Qualitative |

The article examined the individual and social factors that affect HIV/HCV risk among people who use drugs living with or at risk in San Juan, PR. |

The research findings suggest that IUDs in PR face various challenges that affect HIV/HCV and impede treatment, linkage to, and retention in care. The challenges were access to prevention, care, and treatment, social isolation, and stigma. |

| Hepatitis C, stigma, and cure | Marinho R | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines |

The systematic review |

Marinho’s article examined the impact of HCV stigma and how HCV is a mental, psychological, familiar, and social disease, with the primary cause being the lack of adequate HCV information, even in the health professionals setting, causing stigma felt by those affected with HCV. |

The study concluded that chronic hepatitis C is a disease with the stigma associated with it. People infected with HCV experience stigma, anxiety, and fear of transmission, which causes social isolation and reduced intimacy in relationships, which affects the decision to seek treatment and disclose HCV status. The study also concluded that there is a need to bring awareness of the chance of a real cure and eradicate the virus. |

| Stigmatization of Illicit drug use among Puerto Rican health professionals in training | Varas-Diaz N | Quantitative/Q ualitative methods High-depth interview with sequential mixed method |

Qualitative analysis |

The study aimed to explain how social stigma felt by individuals from medical providers is a barrier to treatment in Puerto Rico and how HCV is a stigmatized health condition that continues to be criminalized in Puerto Rico. |

The conclusion of the research findings showed that social stigma affects IDUs in Puerto Rico and how stigma further criminalizes them and contributes to the lack of effective treatment from healthcare professionals. It showed that intervention strategies are needed to reduce stigma among health professionals in training to increase better health outcomes on the island. |

| Felt and enacted stigma among HIV/HCV-coinfected adults: The impact of stigma layering | Lekas H | Qualitative interview |

Qualitative analysis |

The article explored the impact stigma layering of HIV and HCV and the experiences stigma felt among former and current injecting drugs with both diseases. |

The analysis concluded how coinfected individuals perceived and felt about having two stigmatizing diseases and how it impacts intervention. |

Table 4: Results of individual studies.

Results of syntheses

The studies reviewed employed a range of research methodologies to explore the complexities of Hepatitis C (HCV), particularly focusing on how stigma impacts individuals living with the condition. These investigations examined HCV status among participants and explored themes such as stigmatizing attitudes from healthcare professionals, the effect of stigma on treatment adherence, fear of disclosure, and how misinformation contributes to stigma. The recurring theme across the studies was that healthcare provider stigma significantly discourages individuals from seeking care or disclosing their health status.

Collectively, the findings emphasize the struggles faced by People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico and the pressing need for healthcare systems to adopt a more informed and compassionate approach. All seven studies stressed that increasing awareness and understanding of HCV can enhance testing and treatment participation, particularly among Puerto Rican PWIDs.

Researchers utilized search strategies across multiple databases including Google Scholar, PubMed, and PMC, using targeted keywords such as Hepatitis C, Chronic, Therapy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatic cirrhosis, Interferon-alpha, Ribavirin, Social stigma, and Depression. The review encompassed 65 articles examining various HCV-related themes such as the disease’s progression, patient quality of life, therapy options, and the impact of stigma and discrimination. These sources offered in-depth insights into how stigma contributes to delayed diagnosis, treatment gaps, and a diminished quality of life for those affected.

All seven selected studies confirmed that a lack of accurate knowledge regarding chronic illnesses like HCV contributes to harmful stereotypes and misconceptions among healthcare professionals, patients, and the general public. Education and access to HCV-related services are therefore crucial for reducing stigma and infection rates. However, a recurring barrier across the research was the limited availability of HCV services in Puerto Rico, which exacerbates existing healthcare disparities. Stigma remains a major deterrent for individuals needing treatment, as fear and misinformation prevent many from accessing timely care.

In the study by Mate-Gelabert, et al., researchers aimed to uncover gaps in the HCV treatment continuum. The study assessed factors such as testing availability, connection to care, knowledge of treatment options, and participant perceptions. Using descriptive analysis and respondent-driven sampling, data were gathered from 150 individuals. Among them, 84% had been tested for HCV, 87% were HCV antibody-positive, 72% were RNA-positive, 48% were linked to care, 32% were undergoing treatment, 58% had completed treatment, and 71% had been cured. Reported barriers included limited transportation options, healthcare-related stigma, and lack of awareness about treatment locations. The study highlighted the critical need to address gaps in testing, treatment initiation, and retention in care within Puerto Rico’s healthcare system.

Hernández et al., investigated social and individual factors influencing the experiences of PWIDs living with or at risk of HIV and HCV in San Juan. Using an ethnographic approach, researchers conducted 150 field observations, 49 informal interviews with PWIDs, and 19 interviews with staff from community-based organizations. The study utilized transcripts, field notes, and photos to identify patterns and recurring themes. Findings revealed that participants frequently faced social marginalization, limited access to medical and substance use treatment, heightened risk of infection, and inadequate linkage to or retention in care. These outcomes underline the need for innovative intervention models to improve HCV care engagement.

In a systematic review, Treloar, et al.. examined how stigma within healthcare environments influences outcomes for HCV-positive individuals. Reviewing 46 peer-reviewed, evidence-based studies, the authors concluded that provider stigma reduces patient trust and impedes care-seeking behavior. A more trusting and respectful relationship between patients and providers was shown to significantly improve treatment adherence and overall outcomes. Their search strategy utilized keywords such as Hepatitis C, injection drug use, stigma, trust, clinical encounters, and patient-provider relationships to identify relevant literature.

Nyblade, et al., explored how stigma negatively influences healthcare access, diagnostic accuracy, treatment outcomes, and overall patient well-being. The articles included in their analysis were categorized by the type of stigma related to specific diseases and the intervention methods applied. Study quality was assessed using a 27- item Downs and Black checklist, where a score of 14 or above denoted high quality. Additionally, an 18-item quality assessment tool was used, with studies scoring 10 or more also considered highquality. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework guided their review process. Out of 728 peer-reviewed abstracts screened, 68 full-text articles were reviewed, and 37 met the inclusion criteria. Nyblade's findings emphasized the harmful impact of stigma in healthcare environments and highlighted various effective approaches to reduce it.

Varas-Díaz, et al., conducted a study in Puerto Rico investigating stigma directed at PWIDs (People Who Inject Drugs) and its role as a barrier to accessing care. The research included 501 participants. In the qualitative phase, 80 individuals comprising 40 practicing clinicians and 40 students from disciplines such as nursing, psychology, and social work were interviewed. In the quantitative phase, 421 health professional trainees completed standardized questionnaires. The study demonstrated that stigmatizing attitudes toward PWIDs were prevalent among both practicing professionals and students. These attitudes significantly hindered access to appropriate care for individuals with HCV. The authors concluded that comprehensive health education and targeted stigma-reduction interventions are urgently needed for healthcare professionals in Puerto Rico.

Marinho, et al., presented a systematic review on the global HCV epidemic, noting that 170–200 million people are HCV-positive, many of whom are unaware of their infection. The study highlighted the strong connection between stigma and insufficient public and professional education on HCV. The review also emphasized that stigma from healthcare providers remains a significant barrier to HCV treatment and prevention, despite the availability of a cure. Utilizing the PRISMA strategy, the authors screened relevant literature using search terms such as Hepatitis C, PWID, cascade of care, barriers to care, and Puerto Rico. No primary participants were involved in this review, as the analysis was based on previously published literature.

Reporting biases

Among the seven studies included in the review, three exhibited a low to moderate risk of bias due to specific limitations in their methodology:

Mateu-Gelabert, et al., acknowledged limitations related to the reliance on participants’ self-reported HCV status, testing history, and treatment experiences. This raises potential concerns about data accuracy and recall bias.

Varas-Díaz, et al. employed convenience sampling, which may have introduced selection bias and limited the generalizability of the findings. While the study aimed to address stigma toward drug use, its sampling method constrained the representativeness of the population.

Lekas, et al., focused exclusively on underserved minority populations from specific racial and ethnic backgrounds. This narrow demographic scope posed a moderate risk of bias by limiting the applicability of the findings to broader populations.

These limitations are visually represented in Figure 3, which outlines the assessed risk of bias for each included study (Table 5).

Risks of bias in the studies

| Study | Bias due to randomization | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data |

| Understanding Barriers to Hepatitis C Virus care and stigmatization from a social perspective. Treloar, C | Low bias risk | Low bias risk | Low bias risk |

| Hepatitis C virus care cascade among people who inject drugs in Puerto Rico: Minimal HCV treatment and substantial barriers to HCV care. P Mateu-Gelabert, et al. 2023 | Low bias risk | Medium bias risk This study had several limitations. The first limitation was on self-reporting data on HCV testing and HCV history, treatment, and linkage to care. The second was the timeframe of analysis on the HCV cascade of care because it was for a participant’s lifetime, so the self-reported data is limited by the participant’s recollection of receiving HCV-related services, which they may have received a long time before. | Low bias risk The data lacked medical record information that could provide a more detailed medical history. |

| Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it Nyblade, L | Low bias risk | Low bias risk | Low bias risk |

| Understanding how substance use affects HIV and HCV in a layered risk environment in San Juan, Puerto Rico Hernández D | Low bias risk | Low bias risk | Low bias risk |

| Study | Bias due to randomization | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data |

| Hepatitis C, stigma, and cure Marinho RT | Low bias risk | Low bias risk | Low bias risk |

| Stigmatization of illicit drug use among Puerto Rican health professionals in training Varas-DÃaz, N | Low bias risk | Medium Bias risk The study's limitations were the lack of convenience sampling, whose purpose was to understand stigma and how to reduce the stigma related to illicit drug use. | Medium bias risk |

| Felt and enacted stigma among HIV/HCV-coinfected adults: The impact of stigma layering Lekas, H. M | Low Bias risk | Medium bias risk The limitations of the study were associated with the study’s sampling. All the participants were former or current IDUs that belonged to certain racial/ethnic, underserved minority groups. | Medium bias risk The study lacked subsets of coinfected White participants, which was needed for comparison. |

Table 5: Shows the levels of risk of bias of the studies.

Certainty of evidence

This review incorporated seven studies that employed a range of methodological approaches to gather and analyze data. Four of the studies adopted empirical, scientific strategies, including quantitative and qualitative surveys, respondent-driven sampling, referral sampling designs, and rapid ethnographic assessments. These methods ensured a robust exploration of stigma and barriers to care for individuals with HCV.

The remaining three articles applied the PRISMA framework in conjunction with online search strategies to identify peer-reviewed and evidence-based literature. All seven studies were rigorously assessed for potential bias and limitations, as illustrated in Figure 3, which indicates that three of the studies presented a medium to low risk of bias due to issues such as incomplete data or restricted access to participant information.

Despite some limitations, the collective body of work demonstrated strong reliability and validity through the use of diverse data collection methods, such as unstructured interviews, mixed-method surveys, and well-defined sampling techniques. These strategies helped to minimize bias and enhance the overall credibility of the review’s findings.

Discussion

The current review underscores the significant role stigma plays in limiting access to Hepatitis C testing and treatment among People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico. Across the reviewed literature, it became evident that insufficient healthcare access and a lack of public and professional education about HCV are major barriers to managing the virus effectively on the island. Individuals living with chronic conditions such as HCV often face judgment and blame from healthcare providers, further exacerbating the issue.

These findings are consistent with those of earlier systematic reviews, confirming that stigma not only hinders testing and treatment but also perpetuates fear, shame, and avoidance among those most at risk. Enhancing health education for both the public and medical professionals is therefore essential in efforts to reduce stigma and increase service uptake.

One notable gap revealed by the review is the limited availability of epidemiological data on HCV in Puerto Rico. This lack of research restricts the development of tailored public health strategies and impedes efforts to curb the spread of the virus. As noted by Perez, more in-depth studies are needed to understand the behaviors, needs, and lifestyles of vulnerable populations, especially PWIDs.

Additionally, Samali-Lubega highlights the importance of raising awareness among healthcare providers to ensure equitable and stigmafree access to care. Without such improvements, marginalized populations will continue to face barriers that prevent them from seeking timely medical assistance.

The reviewed studies particularly those by Lekas, Marinho, Treloar, and Mate-Gelabert consistently advocate for reducing stigma and expanding healthcare services as crucial strategies for addressing HCV in Puerto Rico. These articles emphasize the urgency of fostering compassion and inclusivity within the healthcare system to ensure that those living with or at risk for HCV feel supported and empowered to pursue care.

In conclusion, addressing systemic stigma, expanding public health education, and improving resource allocation are essential for encouraging more individuals to seek HCV testing and treatment. For Puerto Rico to effectively respond to the HCV epidemic, collaborative efforts between government, healthcare providers, and community organizations must be prioritized to develop sustainable interventions that meet the needs of at-risk populations.

Implications

The findings of this review carry significant implications for policymakers, healthcare providers, and stakeholders involved in delivering and financing healthcare services in Puerto Rico. Given the high prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), particularly among People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs), coordinated efforts are needed to implement effective prevention and intervention strategies to control and ultimately eliminate the virus.

Recommended strategies include expanding research efforts to accurately measure HCV incidence and prevalence within the PWID population, establishing needle exchange programs, improving linkage to care, extending prescription authority for HCV treatment to primary care physicians, and broadening access to direct-acting antiviral therapies. Stigma reduction efforts should focus on educational programs and skill-building workshops for healthcare providers. These initiatives can foster empathy and competence when working with stigmatized populations and help dismantle harmful stereotypes by encouraging direct, humanizing interactions with affected individuals.

While these strategies are promising, they require strong support from federal and territorial governments. This includes increased funding for HCV-related programs, removal of unnecessary treatment restrictions, and expansion of services to reach underserved populations. Without meaningful policy changes and dedicated resources, progress in reducing HCV-related stigma and improving health outcomes in Puerto Rico will remain limited.

Limitations

This review faced several key limitations. One major challenge was the delay between the initial publication of some studies and the completion of the review process. The lag in publishing timelines meant that some findings risked becoming outdated by the time they were analyzed, especially given the evolving nature of HCV treatment and public health interventions. To address this, articles were carefully reviewed for ongoing relevance.

Another limitation was that the review and data extraction were conducted by a single reviewer, increasing the possibility of selection bias or the inadvertent omission of relevant information. This constraint may have impacted the comprehensiveness of the literature included.

Additionally, the scope of this review was narrowed to HCV among Puerto Rican PWIDs a population for which research remains sparse. The limited number of studies focusing specifically on this group creates gaps in understanding the behaviors, perceptions, and health needs related to HCV and stigma. This lack of localized data highlights the urgent need for further research to guide contextually appropriate public health strategies.

It is also important to note that no participants were recruited for this systematic review, and therefore, no risk or harm was posed to any individuals during the research process.

Future research

Identifying the connections between stigma, HCV, and behavior among Puerto Rican PWIDs has been hindered by a scarcity of focused research. To gain a deeper and more accurate understanding of how stigma influences chronic disease outcomes, future studies should expand beyond this narrowly defined population and include a broader range of chronic conditions and affected groups.

Future research should prioritize: Developing standardized methodologies to examine stigma and its effects.

Investigating the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of both healthcare providers and stigmatized individuals.

Conducting comparative studies that evaluate stigma-related interventions across different contexts.

Ensuring inclusion of marginalized and underrepresented populations, particularly Puerto Ricans and other Latinx communities disproportionately affected by HCV.

Furthermore, systematic reviews should adopt multi-reviewer screening and data extraction procedures to improve reliability and reduce potential bias. Research efforts should also aim to explore overlapping stigmas (e.g., drug use, infectious diseases, poverty) to better understand the compounded barriers faced by at-risk individuals.

Ultimately, increasing the volume and quality of research targeting Puerto Rican populations especially those at the intersection of chronic illness and social vulnerability is essential for designing effective public health responses and improving health equity on the island.

Conclusion

Due to limited access to healthcare and insufficient public education regarding Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and substance use, stigma remains a persistent barrier particularly for People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) in Puerto Rico. According to Watson, approximately 95% of individuals diagnosed with HCV have reported experiencing stigma at some point in their lives. This stigmatization can discourage individuals from seeking timely testing and treatment, thereby exacerbating health complications and contributing to increased transmission rates.

Reducing stigma requires a concerted effort to promote and disseminate evidence-based information about HCV. However, in Puerto Rico, systemic challenges including limited healthcare infrastructure, the ongoing migration of medical professionals, and an inadequate response from the U.S. government continue to hinder progress. These issues have left many individuals struggling to manage their condition while the public health crisis worsens.

To effectively address HCV in Puerto Rico, federal agencies must prioritize increased funding, public awareness campaigns, and access to accurate information and treatment resources. Policymakers, healthcare providers, and community-based organizations must collaborate to strengthen the island’s healthcare system and ensure that vulnerable populations, including PWIDs, receive equitable, compassionate, and stigma-free care.

Findings

The articles' titles, abstracts, and introductions were reviewed to ensure their relevance to the research topic. Overall, this screening process ensured that relevant and reliable sources were selected for the research, and the study outcomes were expected to be accurate and insightful. Each of the seven studies showed that the lack of information about chronic conditions, including Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), leads to stigmas and negative perceptions among healthcare providers, patients, and the public. Health education and HCV services are crucial in reducing HCV rates and addressing the associated stigma.

Meaning

There is a severe lack of resources for HCV services in Puerto Rico, leading to a significant challenge. The stigma associated with HCV causes fear and anxiety among individuals with the virus, leading to reluctance to seek treatment. The lack of awareness about HCV is a significant barrier contributing to the stigma. Overall, health education and HCV services are essential in reducing infection rates and addressing the stigma associated with HCV.

Registration and Protocol

No registration number was required for the review.

Support

No financial support, such as funders, sponsors, and grants, were used for the review.

Competing Interest

There was no competing interest in this review.

Availability of data, code, and other materials- The materials and supporting information used for this review are available on Google Scholar.

References

- Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, et al. (1999) The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 341: 556–562.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrion AF, Ghanta R, Carrasquillo O, Martin P (2011) Chronic liver disease in the Hispanic population of the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:834-841.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz DH, Garcia G, Clare C, Su J, Friedman E, et al. (2020) Taking Care of the Puerto Rican Patient: Historical Perspectives, Health Status, and Health Care Access. MededportaL 16:10984.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ginzburg Lerman S (2022) Sweetened Syndemics: diabetes, obesity, and politics in Puerto Rico. J Public Health (Berl.) 30: 701–709.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG (2013) Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 103: 813-821.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heijnders M, van der Meij S (2006) The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med 11: 353–363.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernández D, Castellón PC, Fernández Y, Torres-Cardona FA, Parish C, et al. (2017) When "the Cure" Is the Risk: Understanding How Substance Use Affects HIV and HCV in a Layered Risk Environment in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Health Educ Behav 44:748-757.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim D, Li AA, Perumpail RB, Cholankeril G, Gonzalez SA, et al. (2019) Disparate Trends in Mortality of Etiology-Specific Chronic Liver Diseases among Hispanic Subpopulations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17: 1607–1615.e2

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laraque F, Varma JK (2017) A Public Health Approach to Hepatitis C in an Urban Setting. Am J Public Health 107: 922–926.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lisker-Melman M, Walewski JL (2013) The impact of ethnicity on hepatitis C virus treatment decisions and outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 58:621–629.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] PubMed]

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi