Research Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 9 Issue: 3

The Psychological Effects of Screening Patients at Risk for COVID-19 on Primary Care Professionals in an Ambulatory Setting

Kiran Bhatia1*, Jasvinder S. Bhatia2

1Department of Psychology, Brookline High School, Massachusetts, United States of America

2Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Massachusetts, United States of America

*Corresponding Author: Kiran Bhatia,

Department of Psychology, Brookline High School, Massachusetts, United States of America

E-mail: kiransbhatia@outlook.com

Received date: 14 June, 2023, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-102535;

Editor assigned date: 16 June, 2023, PreQC No. IJMHP-23-102535 (PQ);

Reviewed date: 30 June, 2023, QC No. IJMHP-23-102535;

Revised date: 07 July, 2023, Manuscript No. IJMHP-23-102535 (R);

Published date: 17 July, 2023, DOI: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000223

Citation: Bhatia K (2023) The Psychological Effects of Screening Patients at Risk for COVID-19 on Primary Care Professionals in an Ambulatory Setting. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 9:3.

Abstract

This study investigated the psychological effects of screening patients at risk for COVID-19 on primary care professionals in an ambulatory setting.

A 13 question survey was administered to 24 primary care professionals in an ambulatory setting between designs: A 13 question survey was administered to 24 primary care professionals in an ambulatory setting between June 4th and July 9th. There were yes/no questions, checkbox questions, and an open-ended question focusing on depression and anxiety symptoms. Twenty-four practitioners completed the survey.

The survey response rate was 69%. Analysis of the data showed a strong correlation between seeing patients at risk for COVID-19 and depression and anxiety symptoms among primary care professionals of the respondents, 45.8% felt that they had more trouble concentrating, remembering details, or making decisions. A total of 70.8% of respondents experienced increased fatigue and sleep disturbances, 54.2% felt unexplained irritability or anger, and the same number of respondents experienced fluctuations in appetite and weight. 20.8% of respondents lost pleasure in doing the things they enjoy and 41.7% felt detached from family and friends, and 50% of respondents have had trouble sleeping. 75% of respondents have felt nervousness, restlessness, or have felt tense.

There is a strong psychological effect of screening patients at risk of COVID-19 on primary care professionals, as evidenced by the presence of numerous symptoms of depression and anxiety. Better screening and timely intervention for depression and anxiety among this cohort is warranted to maintain their well-being and allow for the optimization of their patients’ care.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stress; Anxiety, Depression, Primary care, Ambulatory care

Introduction

As of June 14th, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) has found that coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has infected over 767 million people, killed 6.9 million people, and spread to over 200 countries [1]. The psychological effects of seeing patients at risk of COVID-19 on healthcare workers have been documented, yet most of these studies were done internationally and all inpatient [2,3,4]. These previous studies found that anxiety and depression, mental health disturbances and stress were common [5].

Due to the rising numbers of COVID-19 positive patients in hospitals around the United States, many patients are avoiding emergency rooms and instead are seeking advice and treatment for possible COVID-19 symptoms with their local primary care providers, who may not be as well equipped with personal protective equipment or social distancing protocols as larger hospital systems.

This study is intended to explore the feelings of these professionals on treating possible COVID-19 affected patients and the effect these feelings have on their wellbeing.

Materials and Methods

24 primary care professionals at a large primary care practice in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts were given questionnaires inquiring about symptoms of depression and anxiety.

The questionnaire questions were created by the author and based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) criteria for depression and anxiety. It consisted of 13 questions on a worksheet that was distributed by the office manager and returned anonymously in a secure bin, which was emptied by the author every 2 weeks during the study period..

The survey was conducted from June 4th to July 9th, 2020. Respondents were selected at random, and consisted of physicians, nurse practitioners, medical assistants and nurses. The completed questionnaires were entered into the database and the dataset was checked for missing data and outliers. All participants received full explanation of the purpose of this survey and provided informed consent prior to study entry.

Results

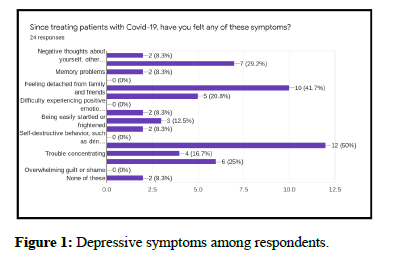

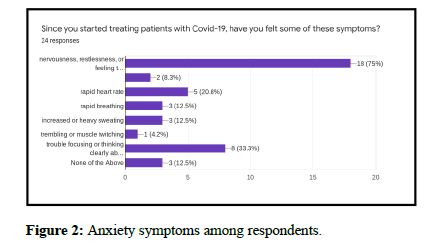

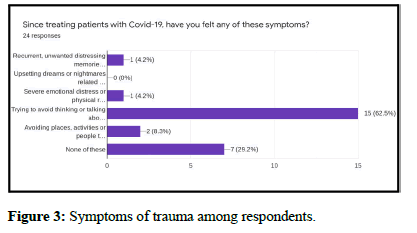

25 questionnaires were returned to the author. One questionnaire was not included due to missing data, which left 24 questionnaires in the final analysis. 45.8% of respondents feel they have more trouble concentrating, remembering details, or making decisions and 70.8% feel they have increased fatigue and sleep problems since they have been screening patients at risk of COVID-19. 54.2% have felt irritable or angry for unclear reasons and the same numbers of respondents have had fluctuations in appetite and weight. 8.3% have had trouble coping with reality and 4.2% have thought about a world without them in it. 41.7% of respondents have occasionally felt sad, anxious, or "empty", 37.5% of respondents have sometimes felt sad, anxious, or "empty", 4.2% of respondents have often felt sad, anxious, or "empty", 12.5% have never felt sad, anxious, or "empty", and one respondent marked “other”, saying it was due to “Not knowing what the future will bring for COVID”. 20.8% of respondents have lost pleasure in doing the things they enjoy and 41.7% have felt detached from family and friends. 50% of respondents have had trouble sleeping (Figure 1). 75% of respondents have felt nervousness, restlessness, or have felt tense, 20.8% of respondents have experienced rapid heart rate, 12.5% of respondents have experienced rapid breathing and the same number have experienced increased or heavy sweating, 4.2% of respondents have experienced trembling or muscle twitching and 33.3% have had trouble focusing or thinking clearly about anything other than COVID-19 (Figure 2). 29.2% of respondents have felt hopeless about the future and 62.5% of respondents have tried to avoid thinking or talking about COVID-19 (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Depressive symptoms among respondents.

Figure 2: Anxiety symptoms among respondents.

Figure 3: Symptoms of trauma among respondents.

Discussion

It has been widely acknowledged that health care providers caring for patients in the inpatient setting have experienced depression and anxiety, but the effect on ambulatory practitioners caring for patients whose COVID status is unknown had not been described [6,7]. This study is the first which has investigated the psychological effect of seeing patients at risk of COVID-19 on primary care professionals in an ambulatory setting and has shown that a large percentage exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety. The findings of increased fatigue and sleep problems, feeling of irritability and unclear anger, and difficulty concentrating are particularly important as this may have an impact on the care delivered to their patients. This study highlights the importance of screening of primary care practitioners for signs of depression and anxiety and the need to intervene in those exhibiting these signs. Interventions such as adequate PPE, appropriate triaging of patients prior to arrival for symptoms or testing may ease some of the tension that is felt. Offering psychology services can also be beneficial for patients who show clear signs of depression and/or anxiety.

The results of this study build on previous research on the mental health and psychosocial effects of medical health workers in China during the COVID-19 epidemic, which found that anxiety and depression was highly prevalent [3,8,9].

Some limitations of our study include the use of a non-validated questionnaire, though the questions that were given were based on DSM-V criteria for depression and anxiety. Another factor that may have influenced the outcome was the location of the practice. At the time of the study, Massachusetts had the 4th most cases in the country and practitioners in less affected states may not have shared the same fears and anxieties [10]. The study was small in size and was done in a single center, but was meant to be an exploratory investigation, which has clearly shown a need to screen more ambulatory primary care practitioners in practices around the country.

Conclusion

This questionnaire exploring common symptoms of depression and anxiety among ambulatory primary care providers screening at risk patients for COVID-19 has shown a high prevalence of these symptoms in the cohort. It can be concluded, therefore, that there is a clear psychological effect of screening patients at risk of COVID-19 on primary care professionals in an ambulatory setting, most likely stemming from depression and anxiety.

References

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. World Health Organization.

- Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, et al. (2020) Psychological impact of COVID-19 on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med 173: 317-320.

- Zhang W, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao W, Xue Q, et al. (2020) Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom 89: 242-250.

- Liu M, Cheng S, Xu K, Yang Y, Zhu Q, et al. (2020) Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross sectional study. Bmj 369: m2195.

- Cooch N (2020) The psychological impact of COVID-19 on physicians: Lessons from previous outbreaks. COVID-19.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3: e203976.

- Spoorthy M, Pratapa S, Mahant S (2020) Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-A review. Asian J Psychiatr 51: 102119.

- Xiong N, Fritzsche K, Pan Y, Lohlein J, Leonhart R, et al. (2022) The psychological impact of COVID-19 on Chinese healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57: 1515-1529.

- Guo WP, Min Q, Gu WW, Yu L, Xiao X, et al. (2021) Prevalence of mental health problems in frontline healthcare workers after the first outbreak of COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19: 103.

- Health DP (2020). Archive of covid-19 cases in Massachusetts. Mass Gov.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi