Case Report, Clin Oncol Case Rep Vol: 3 Issue: 2

Imbalance, Progressive Hearing Loss, and Diplopia: Making Sense of Multifocal Neurologic Disease

David Sanders1* and Alyson Plecash B Kin2

Department of Forestry and Biodiversity, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Agartala, India

*Corresponding Author : David Sanders Gordon, and Leslie Diamond Health Care Centre, Division of Gastroenterology, 5th floor, 2775 Laurel Street, Vancouver, BC Canada V5Z 1M9, Canada E-mail: david.sanders@alumni.ubc.ca

Received: January 21, 2020 Accepted: January 30, 2020 Published: February 07, 2020

Citation: Sanders D, Kin APB (2020) Imbalance, Progressive Hearing Loss, and Diplopia: Making Sense of Multifocal Neurologic Disease. Clin Oncol Case Rep 3:2.

Abstract

Multifocal cranial neuropathy can be associated with infectious, autoimmune, inflammatory, infiltrative, and malignant disease processes. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis is an uncommon presentation of metastatic cancer that can cause multifocal cranial neuropathy with cerebellar dysfunction as in this case. This case report describes the presentation, workup, and disease course of a 69-year-old woman with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. She presented with progressive imbalance, progressive hearing loss, and diplopia and was found to have leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from gallbladder cancer.

Keywords: Imbalance; Progressive hearing loss; Diplopia; Neurologic disease

Introduction

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis is an uncommon presentation of metastatic cancer. Diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis requires a contrast-enhanced MRI of the complete neuroaxis and cerebrospinal fluid for cytology. The most common cancers that cause leptomeningeal carcinomatosis are breast, lung, melanoma, and gastrointestinal cancers. Treatment of the disease includes field radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and intrathecal chemotherapy. Here we present an interesting case of a 69-year-old woman, who presented progressive imbalance, progressive hearing loss, and diplopia who has found to have leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from gallbladder cancer.

Case report

A 69-year-old previously healthy, right-handed female, presented with a four-month course of progressive neurologic dysfunction. She initially noticed trouble with balance and walking, then hearing loss, binocular diplopia, and nausea.

Her first symptom was mild non-specific dizziness. This progressed to significant unsteadiness with ambulation, requiring a cane and then eventually a walker. She developedb left more than right-sided hearing loss with tinnitus, requiring bilateral hearing aids.

The patient’s binocular diplopia was constant, but worse with downgaze, which impeded her ability to read, walk downstairs, and use her phone. She developed posterior bandlike headaches without features of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) that improved but did not resolve with antiinflammatories. Three months into her disease course, the patient began to have post-prandial nausea and infrequent emesis. She developed anorexia with a 10-pound weight loss and some symptoms of early-satiety. There was no dysphagia, odynophagia, abdominal pain, and change in bowel habits or overt gastrointestinal bleeding.

The patient was initially evaluated at a community hospital and referred to a regional center. She was admitted directly from an outpatient neurology clinic appointment to a clinical teaching unit for expedited workup of her progressive neurologic symptoms.

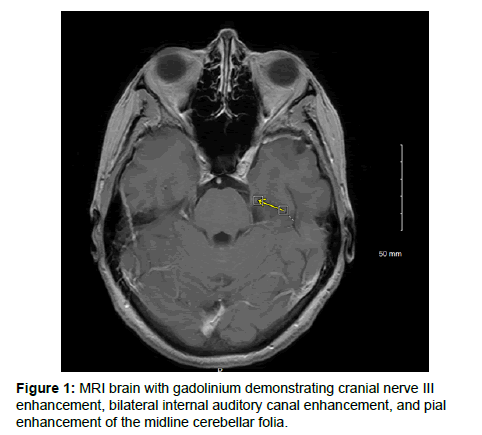

Her physical exam revealed multifocal cranial nerve dysfunction with cerebellar signs. She had vertical binocular diplopia on primary gaze, worst with left and downgaze, decreased hearing bilaterally. Motor and sensory exams were normal. There were mild ataxia and gait was wide-based (Figure 1).

Given the multifocal central nervous system process suspected, an MRI brain with gadolinium was performed (Figure 1). MRI revealed leptomeningeal enhancement of the seventh and eighth cranial nerves bilaterally at the internal auditory canals and of the left third cranial nerve. There was the perineural enhancement of the left fifth cranial nerve extending along its course into Meckel's cave, the left cavernous sinus, and minimally into the foramen ovale. Pial enhancement was also appreciated within multiple cerebellar folia of the cerebellar vermis (Table 1).

| Neoplastic | Primary-lymphoma, gliomatosis cerebri, skull base tumor |

| Secondary-leptomeningeal carcinomatosis (from a CNS or distant primary) | |

| Paraneoplastic | |

| Infectious (Meningitis) | Bacterial-TB, syphilis, lyme disease, mycoplasma |

| Viral-HIV, PML (JC virus) | |

| Fungal-cryptococcus | |

| Inflammatory | Neurosarcoidosis |

| Bickerstaff (post-infectious process) | |

| Autoimmune | Bechet’s |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | |

| Vasculitis | |

| Tolosa-Hunt | |

| Sjogren’s | |

| Amyloidosis | |

| Demyelinating diseases | - |

Table 1: Differential diagnosis for multifocal CNS process in a well patient without cortical features.

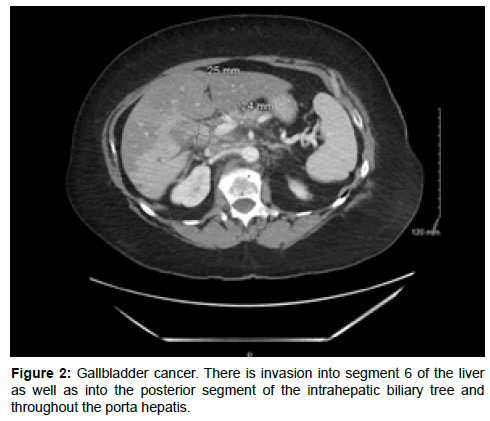

Given the suspicion for leptomeningeal carcinomatosis vs infectious etiologies vs an inflammatory cause, a broad workup was pursued. Basic blood work was unremarkable, apart from a mild elevation in both GGT at 244 (U/L) and alkaline phosphatase at 217 (U/L). Hepatocellular enzymes were near normal with an AST of 30 (U/L) and an ALT of 41 (U/L). CSF showed a WBC count of 377 (× 106 cells/L) with lymphocytic predominance (44%). The protein level was 2.52 g/L. Acidfast bacilli stain and cryptococcal antigen were negative. A paraneoplastic panel (on serum and CSF) was negative (Figure 2).

The CSF cytology showed atypical cells. The thin prep slide preparation showed metastatic non-small cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was strongly positive for CEA and cytokeratin 7 and weakly positive for CDX-2. IHC stains were highly suspicious for metastatic adenocarcinoma from the gastrointestinal tract. Her CT abdomen (Figure 2) showed an ill-defined mass centered at the porta hepatis, in the region of the gallbladder neck, measuring approximately 2.5 × 2.4 × 2.9 cm in size. The liver metastasis biopsy showed adenocarcinoma and IHC stains were consistent with gallbladder origin. Upon oncology review, she was not a candidate for any intrathecal chemotherapy given a rapid functional decline, and she passed away within approximately 2 months of diagnosis.

Discussion

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis is cancerous infiltration of the arachnoid and pia mater, that surround the brain and spinal cord. Other causes of diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement include meningitis, encephalitis, hemorrhage, granulomatous conditions (i.e. neurosarcoidosis), post-operative, and posttraumatic changes. Tumor cell deposition in CSF occurs by multiple mechanisms, including a direct extension from vertebral, subdural, or epidural metastases, hematogenous seeding, spread from choroid plexus, and retrograde transport along nerves [1]. Malignant de novo tumors, like primary leptomeningeal melanomatois, arising in the meninges are also possible. The more common symptoms of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis include headache (from either increased intracranial pressure or meningeal irritation), back pain, and nausea/vomiting [2]. Clinically, intracranial leptomeningeal carcinomatosis can cause multifocal neurologic deficits, altered mental status, seizures, and cerebellar dysfunction. Diplopia can result from the involvement of CN III, IV or VI. Trigeminal nerve and facial nerve involvement are also described [2]. Sensorineural hearing loss tends to be a late finding. Focal cortical signs are less common. Pituitary dysfunction is also possible if there is an invasion of the pituitary stalk.

For a diagnosis of leptomeningeal disease, MRI brain and full spine with gadolinium and CSF for cytology are critical complementary investigations. If a primary malignancy is unknown, targeted investigations for diagnosis are also required. Whenever possible, contrast-enhanced MRI should be performed prior to lumbar puncture to avoid false-positive meningeal enhancement [2]. Common areas to look for enhancement on imaging include the cerebellar folia (as in our case), cerebral sulci, cauda equina, or basal cisterns [3]. For CSF cytology, guidelines recommend collecting between 5-10 mL of CSF and having it sent to the laboratory immediately for best results [2]. In addition to positive cytopathology, CSF findings of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis include increased opening pressure, increased WBC count, elevated protein, and decreased glucose. False-positive cytology is rare, but negative cytology does not rule out leptomeningeal carcinomatosis given the varying rates of sensitivity [2]. The most common cancers that cause leptomeningeal carcinomatosis are breast, lung, melanoma, and gastrointestinal cancers. Primary tumors of the brain that can infiltrate the leptomeninges include astrocytomas, pineoblastomas, ependymomas, and medulloblastomas.

Gallbladder cancer is an uncommon cancer in western countries (Canada, UK, US, Australia) with a lower incidence in men (0.4-0.8 per 1000,000) compared to women (0.6-1.4 per 100,000) [4]. Often, it is asymptomatic until late in the disease course, however, presenting symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, and anorexia in some patients. Generally, about 10% of cases present early enough in the disease course for surgical resection [4]. On physical examination, Courvoisier’s sign is a palpably enlarged gallbladder. Gallbladder cancer is predominately adenocarcinoma [5,6] and can spread locally to invade into the liver, biliary ducts, lymph nodes and blood vessels [6]. Less commonly, patients present with distant metastasis, paraneoplastic syndromes, or paraneoplastic dermatosis. Central Nervous System (CNS) involvement with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in gallbladder cancers, as in the present case, is exceedingly rare.

Treatment of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis includes field radiotherapy, chemotherapy (gemcitabine-cisplatin), and intrathecal chemotherapy but is often limited by performance score, tumor type, and location [7]. Corticosteroids can be used to treat symptoms secondary to compression or increased intracranial pressure [8,9]. Intrathecal chemotherapy can be delivered through an Ommaya reservoir or by lumbar puncture [9]. Prognosis and life expectancy are dependent on tumor type, location, and performance status. The goal of therapy is to treat symptoms and prevent disease spread, but leptomeningeal carcinomatosis is incurable.

Conclusion

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis must be suspected in any individual presenting with multifocal neurologic disease, and especially in the presentation of multiple cranial neuropathies. Diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis can be made based on clinical presentation with leptomeningeal enhancement on post-gadolinium MRI and/or positive cytology in the CSF. Investigation for the primary malignancy is suggested for tissue diagnosis, especially if cytology is bland. Prognosis depends on tumor type and location, however leptomeningeal disease, as presented in the current case, is incurable.

References

- Kokkoris CP (1983) Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis: How does cancer reach the pia-arachnoid? Cancer 51: 154-160.

- Clarke JL (2012) Leptomeningeal metastasis from systemic cancer. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 18: 328-342.

- Drappatz J, Batchelor T (2005) Leptomeningeal and peripheral nerve metastases. Continuum11: 47-68.

- Kanthan R, Senger JL, Ahmed S, Kanthan SC (2015) Gallbladder cancer in the 21st Century. J Oncol 2015: 967472.

- Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, et al. (2008) Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). J Surg Oncol 98: 485.

- Ebata T, Ercolani G, Alvaro D, Ribero D, Di Tommaso L, et al. (2016) Current status on cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer. Liver Cancer 6: 59-65.

- Zaidi MY, Maithel SK (2018) Updates on gallbladder cancer management. Curr Oncol Rep 20: 21.

- Grossman SA, Krabak MJ (1999) Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Rev 25: 103-119.

- Leal T, Chang JE, Mehta M, Robins HI (2011) Leptomeningeal metastasis: Challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Cancer Ther Rev 7: 319-327.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi