Case Report, Clin Oncol Case Rep Vol: 5 Issue: 5

Pseudocirrhosis in Metastatic Breast Cancer in a Male Successfully Treated with Leuprorelin and Anastrozole Followed by Eribulin: A Case Report

Hafez Golzarian1*, Morgan Turnow2, Alaha Mariam1, Sidra R. Shah1, Syed H. Haq1, Benjamin A. Pasley1, Christopher J. Hawkins1, Rajpal Aujla1 and Joseph J. Sreenan3

1Department of Internal Medicine, BonSecours Mercy Health-St. Rita’s Medical Center, Lima, OH, USA

2University of Pikeville Kentucky College of Osteopathic Medicine, Pikeville, KY, USA

3Department of Clinical Pathology, BonSecours Mercy Health-St. Rita’s Medical Center, Lima, OH, USA

*Corresponding Author: Hafez Golzarian

Department of Internal Medicine, Mercy Health - St. Rita's Medical Center, 751 West Market Street, Lima, Ohio 45801, USA

E-mail: HGolzarian@mercy.com

Received: May 07, 2022; Manuscript No: COCR-22-63046;

Editor Assigned: May 09, 2022; PreQC Id: COCR-22-63046 (PQ);

Reviewed: May 22, 2022; QC No: COCR-22-63046 (Q);

Revised: May 24, 2022; Manuscript No: COCR-22-63046 (R);

Published: May 31, 2022; DOI: 10.4172/cocr.5(5).231

Citation: Golzarian H, Turnow M, Mariam A, Shah SR, Haq SH, et al. (2022) Pseudocirrhosis in Metastatic Breast Cancer in a Male Successfully Treated with Leuprorelin and Anastrozole Followed by Eribulin: A Case Report. Clin Oncol Case Rep 5:5

Abstract

Introduction: There are very few studies and cases in the literature describing metastatic breast cancer in the male population, accounting for less than one percent of all cases. Of those who have been reported, the vast majority fail to survive beyond five years from time of diagnosis. The lack of literature in this population makes it difficult for clinicians to foresee and prepare for upcoming complications in management. One of the more serious complications in managing metastatic breast cancer is the development of pseudocirrhosis, a frequent long-term side effect of chemotherapy and/or radiation typically seen in patients with malignancy in the liver.

Case Presentation: We report the case of a 48-year-old male with a completely unremarkable family, medical, and social history other than a homozygous mutation in his MTHFR gene who was diagnosed with stage IV ER/PR-positive, HER-2/neu negative, BRCA1 and BRCA2-negative breast cancer with metastasis to bone, lung, and liver. He was successfully treated with an initial regimen consisting of radiation, Denosumab, Leuprorelin, and Anastrozole. After completing five years of hormone therapy, he was initiated on Eribulin. Eight years since time of diagnosis, he continues to survive and undergo symptomatic management of long-term side-effects of his treatments.

Conclusions: To our knowledge this is the only reported case of metastatic breast cancer with pseudocirrhosis in a male patient. It is imperative to report this unique case to help increase awareness for clinicians managing other males with breast cancer. What makes this case even more reportable is the good outcome overall as our patient remains alive and well eight years since time of diagnosis, a relatively difficult and rare feat to achieve in end-stage breast cancer.

Keywords: Pseudocirrhosis; Male Breast Cancer; Metastasis; Ascites; Anastrozole; Eribulin

Abbreviations

Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR), Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER-2), Intravenous (IV), Computerized Tomography (CT), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP)

Introduction

Breast cancer in males is rare, representing roughly only one percent of all breast cancers worldwide [1]. Cases of males with metastatic breast cancer who’ve successfully been treated and surpassed five-year s urvivability are e ven l ess p revalent. A common complication of breast cancer with metastasis to the liver is pseudocirrhosis. However, to our knowledge we are the first to report such a case in a male. Pseudocirrhosis refers to changes in the liver that mimic cirrhosis, however the typical histological findings seen in cirrhosis are absent [2-5]. It is characterized by multifocal capsular retraction, enlargement of the caudate lobe, and nodularity of the liver. [2,6] Pseudocirrhosis commonly occurs in patients with metastatic breast cancer, although it has been reported in other malignancies, such as lung and gastric adenocarcinoma. [4,7,8] The mechanism and cause of pseudocirrhosis in relation to breast cancer remains unclear [9]. The leading proposed mechanism is the conversion of previously viable tissue into scarred and physiologically dead tissue as a result of chemotherapy and/or radiation. Often the areas of damage are at the sites previously invaded by cancer cells.

Regarding metastatic breast cancer, the literature does have several cases of pseudocirrhosis in women undergoing chemotherapy; however, no cases of pseudocirrhosis have been previously reported in a male patient until now.

Case Report

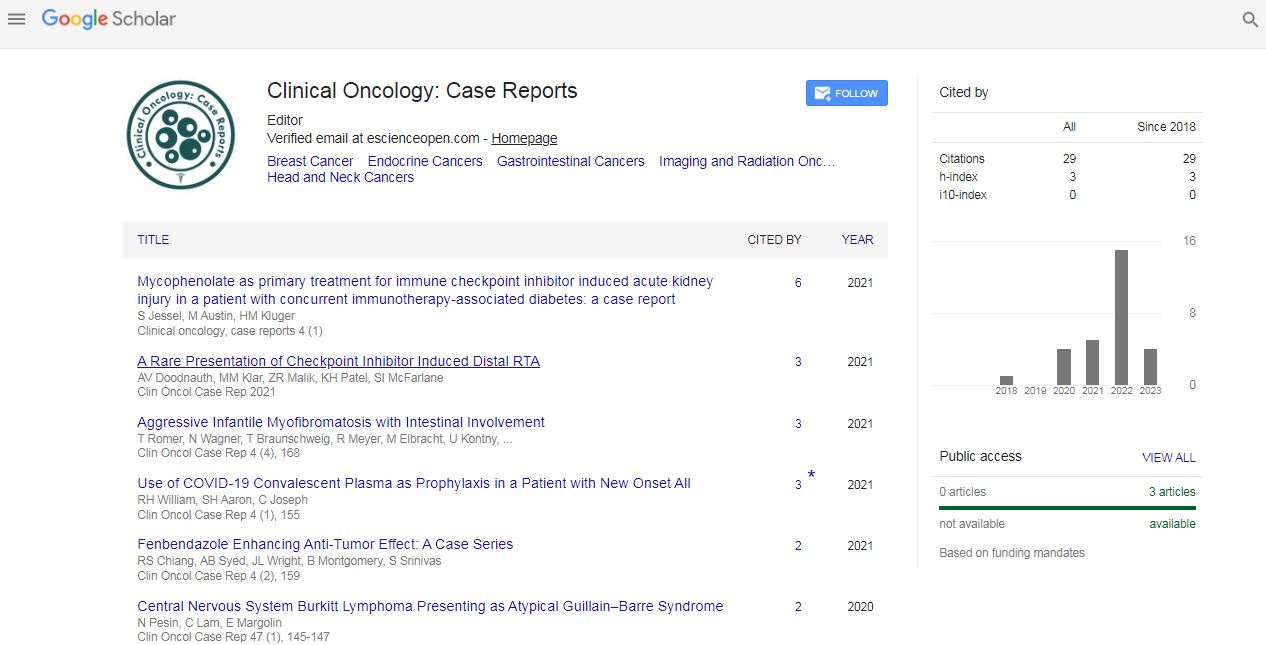

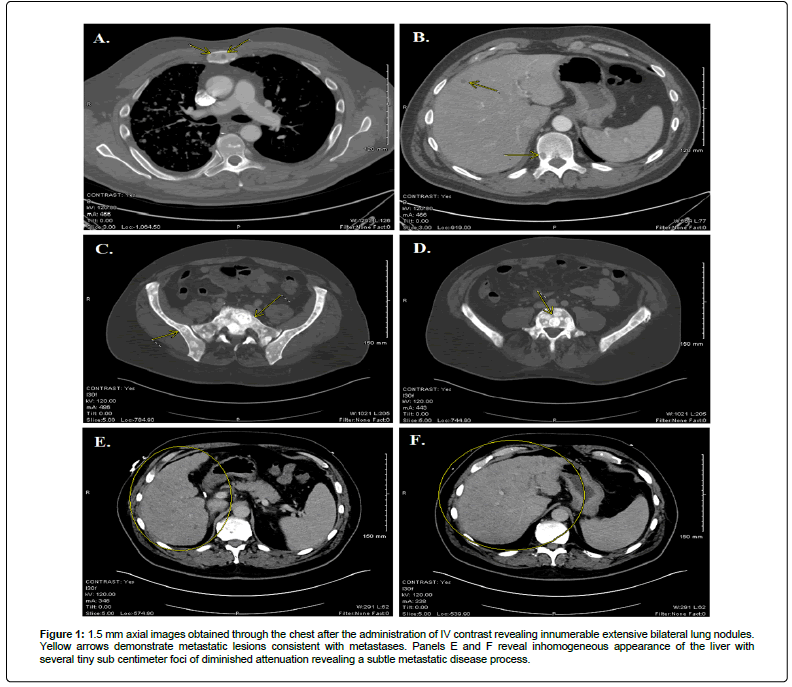

We present the case of a 48-year-old male with a completely unremarkable family, medical, and social history other than a homozygous MTHFR A1298C gene mutation who initially presented with a constellation of symptoms including back pain, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and increased dyspnea on exertion. Computed Tomography (CT) of the chest with Intravenous (IV) contrast revealed some diffusely scattered small subsegmental pulmonary emboli (Figure 1). However, a highly suspicious lesion was also visualized on the sternum as well as the liver which raised concerns for malignancy (Figure 1). Thus, a full body bone scintigraphy was obtained which revealed diffuse areas of increased nuclear activity compatible with metastatic disease in the spine, ribs, sternum, right scapula, and possibly the right shoulder (Figure 2). A thorough physical exam revealed an abnormal area of hardened periareolar tissue. Subsequent excisional breast biopsy revealed the final diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer that was ER/PR-positive, HER-2/neu negative. Additional testing confirmed the cancer to be BRCA1 and BRCA2-negative.

Figure 1: 1.5 mm axial images obtained through the chest after the administration of IV contrast revealing innumerable extensive bilateral lung nodules. Yellow arrows demonstrate metastatic lesions consistent with metastases. Panels E and F reveal inhomogeneous appearance of the liver with several tiny sub centimeter foci of diminished attenuation revealing a subtle metastatic disease process.

Figure 2: Whole body bone scintigraphy scan revealing areas increased activity compatible with metastatic disease in the spine, tip of the 7th rib on the right, sternum, right scapula, and clavicles. Whole body bone scintigraphy scan revealing areas increased activity compatible with metastatic disease in the spine, tip of the 7th rib on the right, sternum, right scapula, and clavicles.

He completed five treatments of palliative radiation to the lumbar spine and right shoulder and was placed on Tamoxifen which was discontinued after one year due to intolerable side effects of thromboemboli. He developed multiple pulmonary emboli, deep vein thrombi, splenic vein thrombus, and hepatic vein thrombus. He was started on daily Enoxaparin injections and switched to a regimen consisting of Denosumab, Leuprorelin, and Anastrozole for the next four years. Serial Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans and down-trending tumor markers confirmed that he was responding well to this regimen. Upon five-year completion of hormone therapy, he was then started on Eribulin and has been on this since. Overall, he had an excellent outcome, and we were able to provide him an increased quantity of life while preserving as much quality as possible.

Unfortunately, over the years he began to develop abdominal distention and ascites. Per previous CT images, patient had a relatively healthy liver. However, by year five post-diagnosis, he began to develop a nodular appearing liver along with grade I/II ascites requiring outpatient paracentesis as needed. Fluid analysis consistently revealed a yellow amber color, thin consistency, clear, with cytology showing rare, atypical single cells most likely being reactive histiocytes. Cell count with differential revealed total nucleated cell count of 54 cells/uL, minimal red blood cell count of <2000 cells/uL, and fluid albumin 0.5 gm/dl. Fluid immunohistochemistry was performed for GATA3, ER, calretinin, and WT-1 with adequate controls. The atypical cells were negative for all the aforementioned tests. Additional testing revealed no evidence of hepatitis A, B, or C. Blood chemistry revealed the following: total protein 4.1 g/dL; albumin 2.4 g/dL; total bilirubin 1.4 mg/dL; Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) 25 IU/L; Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) 18 IU/L; Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), 86 IU/L.The decision was made to drain his ascites as needed and initiate furosemide and spironolactone. Additionally, he was placed on a low sodium diet with fluid restriction of 1.5 L.

Over the years he underwent multiple upper endoscopies that revealed esophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy that gradually worsened with time. We continued symptomatic management as needed. Today, he is eight years post-diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer and four years since onset of his ascites and is still relatively doing well overall, but his ascites has progressed to grade III. His Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score has been typically ranging 18-24 with chronic hypoalbuminemia, chronic mild hyponatremia, portal hypertension with occasional variceal bleed requiring banding, and recurrent ascites requiring aggressive paracentesis biweekly with removal of 5 L-7 L of fluid per session.

Discussion and Conclusion

Because our patient’s metastatic breast cancer was hormone receptor positive, the decision was made to place him on a regimen that consisted of denosumab, leuprorelin, and anastrozole. Systemic chemotherapy is usually the treatment of choice for individuals with metastatic breast cancer, however complications such as pseudocirrhosis of the liver may occur post-treatment [2, 3, 10-12].

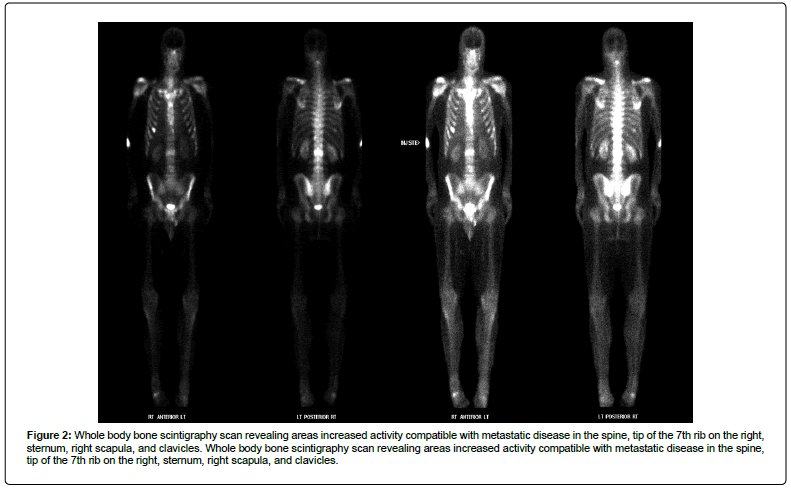

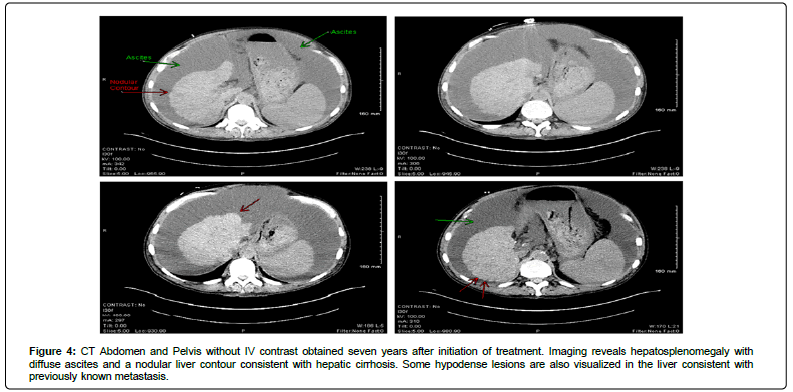

Pseudocirrhosis is a serious complication in patients with metastatic breast cancer undergoing treatment and is associated with increased mortality. While pseudocirrhosis has been described in multiple different malignancies, breast cancer is the most common. Nearly two-thirds of breast cancer patients with metastasis to the liver will eventually develop pseudocirrhosis. In pseudocirrhosis, one or more of the stages of progression to a true cirrhotic state are bypassed (Figure 3). In the case of our patient, he previously only had mild-moderate fatty liver disease at most (Figure 1). However, upon his metastasis, he received radiation therapy followed by five years of hormone therapy followed by three more years of Eribulin while gradually developing pseudocirrhosis (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Typical stages of liver damage and progression towards cirrhosis (black arrows). Blue arrows demonstrate the pathogenesis of pseudocirrhosis.

Figure 4: CT Abdomen and Pelvis without IV contrast obtained seven years after initiation of treatment. Imaging reveals hepatosplenomegaly with diffuse ascites and a nodular liver contour consistent with hepatic cirrhosis. Some hypodense lesions are also visualized in the liver consistent with previously known metastasis.

The pathophysiology is believed to be multifactorial. The leading hypothesis is that it is a combination of drug-induced fibrosis, sinusoidal scarring and obstruction, and microthrombi throughout the vasculature of the liver due to the hypercoagulability of the metastatic state resulting in chronic ischemic nodular hyperplasia. [3, 12] For these reasons, we believe our patient was especially at high risk for developing pseudocirrhosis because of his MTHFR mutation resulting in increased thrombi and hepatic occlusive disease. After all, he did end up suffering from multiple thrombi. His occlusive disease was exacerbated by his malignancy which is why he was indefinitely placed on daily Enoxaparin injections. Additionally, he received five sessions of radiation to his lumbar spine and left shoulder which may have led to an extent of fibrosis and sinusoidal collapse. Over time, the addition of Eribulin likely added insult to liver injury via mechanisms discussed above. There are many chemotherapeutic agents known to cause pseudocirrhosis and other forms of liver injury. However, Eribulin is not one of the typically listed agents. The very first reported case of Eribulin-induced pseudocirrhosis was by Akdeniz et al in 2018 where they reported two cases of pseudocirrhosis in patients taking Eribulin [13]. Oddly enough, our patient’s onset of abdominal distention and ascites was five months after initiation of Eribulin. We cannot rule out Eribulin as a major culprit of his pseudocirrhosis.

Unfortunately, a state of such metastasis precludes such patients from being able to qualify for liver transplants as the immunosuppressants would likely result in relapse and recurrence of malignancy. Thus, conservative symptomatic management remains to be the mainstay approach in patients with pseudocirrhosis. A Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) may be an option for such patients. However, such procedures are very high-risk and recent literature is showing mixed results in success. Although associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality, our patient has been living with pseudocirrhosis for roughly four years now. Our patient was provided the option for TIPS, but it was refused at the time. As of today, our patient has completed over 150 paracenteses since initial onset of his pseudocirrhosis four years ago but continues to perform activities of daily living with minimal difficulty. Additional cases will need to be reported to better understand and manage male breast cancer patients who are prone to similar complications as their female counterparts.

References

- Gucalp A, Tiffany AT, Joel RE, Joel SP, Sara RS, et al. (2019) Male breast cancer: a disease distinct from female breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 173: 37-48. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Gopalakrishnan D, Shajihan A, Purysko AS, Abraham J (2021) Pseudocirrhosis in breast cancer experience from an academic cancer center. Front Oncol 11: 679163. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Lee SL, Eun DC, Sae JN, Jeong SK, Ho JA, et al. (2014) Pseudocirrhosis of breast cancer metastases to the liver treated by chemotherapy. Cancer Res Treat: Official J Korean Cancer Ass 46: 98. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Shijubou N, Toshiyuki S, Yoshiko K, Hideaki S, Yuta N, et al. (2021) Pseudocirrhosis due to liver metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma. Thoracic Cancer 12: 2407-2410. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Oliai C, Michael LD, Caelainn R, Bhutada A, Phillip SG, et al. (2019) Clinical features of pseudocirrhosis in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 177: 409-417. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Jeong WK, Choi SY, Kim J (2013) Pseudocirrhosis as a complication after chemotherapy for hepatic metastasis from breast cancer. Clin Mol Hepatol 19: 190-194. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Adike A, Karlin N, Menias C, Carey EJ (2016) Pseudocirrhosis: A case series and literature review. Case Rep Gastroenterol 10: 381-391. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Mitani S, Kadowaki S, Taniguchi H, Muto H, Muro K (2016) Pseudocirrhosis in gastric cancer with diffuse liver metastases after a dramatic response to chemotherapy. Case Rep Oncol 9: 106-111. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Aoyagi T, Takabe K, Tamanuki T, Matsubara H, Matsuzaki H (2018) Pseudocirrhosis after chemotherapy in breast cancer, case reports. Breast Cancer 25: 614-618. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Engelman D, Moreau M, Lepida A, Zaouak Y, Paesmans M, et al (2020) Metastatic breast cancer and pseudocirrhosis: An unknown clinical entity. ESMO Open 5 : e000695. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Adler M, Tang I, Gach MW, MacFaul G (2019) Recurrent metastatic breast cancer presenting with portal hypertension and pseudocirrhosis. BMJ Case Rep 12: 231044. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sass DA, Clark K, Grzybicki D, Rabinovitz M, Shaw-Stiffel TA (2007) Diffuse desmoplastic metastatic breast cancer simulating cirrhosis with severe portal hypertension: A case of ‘pseudocirrhosis’. Dig Dis Sci 52: 749-752. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Akdeniz N, Ali Kaplan M, Kucukoner M, Urakcı Z, Karhan O, et al. (2018) Pseudocirrhosis in patients with metastatic breast cancer after treatment with eribulin. World J Surg Surg Res 1: 1057. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi