Research Article, Res Rep Math Vol: 1 Issue: 1

From Configurations to Branched Configurations and Beyond

Jean-Pierre Magnot*

Department of Forestry and Biodiversity, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Agartala, India

*Corresponding Author : Jean-Pierre Magnot

Department of Mathematics, University of Angers, Lycee Jeanne dArc, 30 avenue de Grande Bretagne, F-63000, Clermont-Ferrand, France

Tel: +33 2 41 96 23 23

E-mail: jean-pierr.magnot@ac-clermont.fr

Received: July 19, 2017 Accepted: October 18, 2017 Published: November 02, 2017

Citation: Magnot JP (2017) From Configurations to Branched Configurations and Beyond. Res Rep Math 1:1

Abstract

We propose here a geometric and topological setting for the study of branching effects arising in various fields of research, e.g. in statistical mechanics and turbulence theory. We describe various aspects that appear key points to us, and finish with a limit of such a construction which stand in the dynamics on probability spaces where it seems that branching effects can be fully studied without any adaptation of the framework.

Keywords: Finite and infinite configuration spaces; Branched dynamics

Introduction

Finite and infinite configuration spaces are rather old topics, see e.g. [1,2] and the references cited therein, that had many applications in various settings in mathematical physics and representation theory. More recently, several papers, including [3-6] showed how these topics could be applied in various disciplines: ecology, financial markets, and so on. This large spectrum of applications principally comes from the simplicity of the model: considering a state space N, finite or infinite configurations are finite or countable sets of values in N: This is why we begin with giving a short description of this setting, and describe a differentiable structure that can fit with easy problems of dynamics. This structure, which can be seen either as a Frölicher structure or as a diffeological one, is carefully described and the links between these two frameworks are summarized in the appendix. We also give a result that seems forgotten in the past literature: the infinite configuration space used in e.g. [7] is an infinite dimensional manifold.

But the main goal of this paper is to include one dimensional turbulence effects (in particular period doubling, see e.g. [8]) in the dynamics described by finite or infinite configuration spaces. For this, we change the metric into the Hausdorff metric. This enables to “glue together” two configurations into another one and to describe shocks. Therefore, the dynamics on this modified configuration space are described by multivalued paths that are particular cases of graphs on N; which explains the terminology: “branched configuration”.

We finish with the description of the configurations used e.g. in optimal transport, the space of probability measures, and shows how they can also furnish configurations for uncompressible fluids. In these settings, branching effects are well-known and sometimes obvious, and we do not need any adaptation of the framework to obtain a full description of them. Therefore, what we call branched configurations appears as an intermediate (an we hope useful) step between dynamics of e.g. a N-body problem and e.g. wave dynamics.

Dirac configuration spaces on a locally compact manifold

Let us describe step by step a way to build infinite configurations, as they are built in the mathematical literature. We explain each step with the configurations already defined in e.g. Albeverio et al. [7] and Fadell et al. [1], the generalization will be discussed later in this paper.

A set of I -configurations is a set of objects that are modelizations of physical quantities. For example, in the settings [1-6], the physical quantity modeled is the position of one particle. The whole world is modeled as a locally compact manifold N, and the set of 1-configurations is itself N, or equivalently the set of all Dirac measures on N.

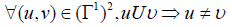

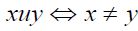

Let I be a set of indexes. I can be countable or uncountable. We define the indexed (or the ordered if I isequipped with its total order) configuration spaces. For this, we need to define a symmetric binary relation relation u on Γ1, that expresses the compatibility of two physical quantities. We assume also that u has the following property:

In the settings Albeverio et al. [7] and Finkelshtein et al. [1], two particles cannot have the same position. Then, for x, y ∈ N [2],

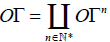

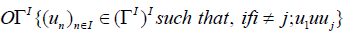

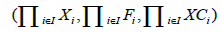

With these restrictions, we can define the indexed or ordered configuration spaces:

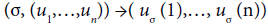

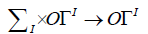

The general configuration spaces are not ordered. Let Σn be the group of bijections on  , and ΣI be the set of bijections on I. We can define two actions:

, and ΣI be the set of bijections on I. We can define two actions:

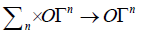

and its infinite analog:

where ΣI is a subgroup of the group of bijections of I: In the sequel, I is countable with discrete topology, which avoids topological problems on ΣI as in more complex examples. Then, we define general configuration spaces:

Configuration spaces on more general settings

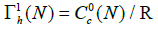

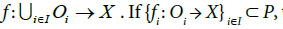

In the machinery of the last section, the properties of the base manifold N are not used in the definition of the space Γ1. This is why the starting point can be Γ1 instead of N, and we can give it the most general differentiable structure. Let us first consider the most general case [9]:

Proposition 1.1: If Γ1 is a diffeological space, then Γn, Γ and ΓI are diffeological spaces

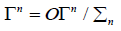

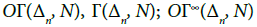

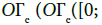

Proof: (Γ1)n (resp. (Γ1)N) is a diffeological space according to Proposition 4.8 (resp. Proposition 4.10), so that, OΓn (resp. OΓI) is a diffeological space as a subset of (Γ1)n (resp. (Γ1)N). Thus, Γn = On/ Σn (resp. Γ1 = On/Σ) has the quotient diffeology by Proposition 4.12, which ends the proof.

Let us now turn to the cases where ΓI has a stronger structure. We already know that Γn is a manifold if Γ1 is a manifold.

Proposition 1.2: If Γ1 is a Frölicher space, then Γn (and hence Γ) is a Frölicher space.

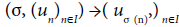

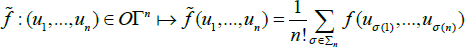

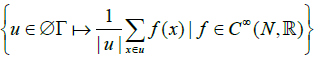

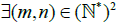

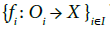

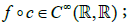

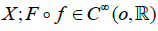

Proof: Adapting the last proof, using Proposition 4.9 instead of Proposition 4.8, we get that OΓn is a Frolicher space if Γ1 is a Frolicher space. Let us now build a generating set of functions for the Frolicher structure on OΓn. Let f:  be a smooth map. We define the symmetrization of f:

be a smooth map. We define the symmetrization of f:

The set of functions  generate the contours on OΓn, and then, passing to the quotient, generate the contours on Γn

generate the contours on OΓn, and then, passing to the quotient, generate the contours on Γn

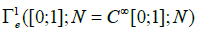

Setting a Frölicher structure on indexed configurations is only a straightforward consequence of Proposition 4.10:

Proposition 1.3: If Γ1 is a Frölicher space, then OΓI is a Frölicher space.

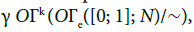

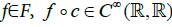

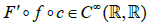

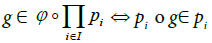

But the problem of a Frölicher structure on ΓI a little bit more complicated; let us explain why and give step by step the construction of the Frölicher structure. We first notice that the contours of the Frölicher push forward naturally by the quotient map  ut, if one wants to describe a generating set of functions, by Proposition 4.9, one has to consider all combinations of a finite number of smooth functions

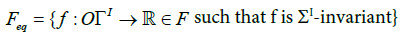

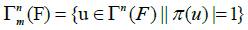

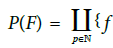

ut, if one wants to describe a generating set of functions, by Proposition 4.9, one has to consider all combinations of a finite number of smooth functions  This generating set does not contain any ΣI -invariant function, except constant functions. This is why the approach used in the proof of the Proposition 1.2 cannot be applied here. For this, one has to consider the set

This generating set does not contain any ΣI -invariant function, except constant functions. This is why the approach used in the proof of the Proposition 1.2 cannot be applied here. For this, one has to consider the set

of equivariant functions on OΓI: This discusssion can become very quickly naïve and we prefer to leave this question to more applied works in order to fit with known examples instead of dealing with too abstract considerations.

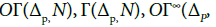

Topological Configuration Spaces

In this section, we present examples of 1-configurations and their associated configuration spaces. Manifolds will replace the Dirac measures used in Albeverio et al. [7]. In the sequel, N is a Riemannian smooth locally compact manifold. The 1-configurations considered keep their topological properties, as in the model of elastodymanics (see e.g. Hughes et al. [10]) or in various quantum field theories. Notice also that we do not give compatibility conditions between two 1-configurations: we would like to give the more appropriate conditions in order to fit with the applied models, this is why we leave this point to more specialized works.

Topological 1-configurations

We follow here, for example, Hughes T et al. [10].

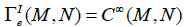

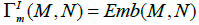

Definition 2.1: Let M be a smooth compact manifold and N an arbitrary manifold. We set

One can also only consider embeddings, and set:

where dimM<dimN, and Emb is the set of embeddings. The things run as in the first case, since  is an open subset of

is an open subset of

Examples of topological configurations

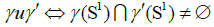

Links. Let  Here, we fix the uncompatibility relation as

Here, we fix the uncompatibility relation as

Then,  is the space of n→links of class Ck, which is a Frechet manifold.

is the space of n→links of class Ck, which is a Frechet manifold.

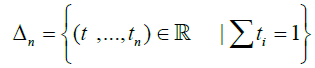

Triangulations: Consider the n-simplex

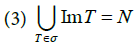

If N is a n-dimensional manifold, a (finite) triangulation σ of N is such that:

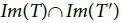

(2) Let  such that T≠ T′ then

such that T≠ T′ then  is a simplex or a collection of simplexes of each border Im(∂T) and Im

is a simplex or a collection of simplexes of each border Im(∂T) and Im  :

:

We get by condition 2 a compatibility condition u; for which we can build  and

and  If N is compact, the set of triagulations of N is a subset of

If N is compact, the set of triagulations of N is a subset of  If N is non compact and locally compact, the set of triangulations of N is a subset of

If N is non compact and locally compact, the set of triangulations of N is a subset of

More generally, for p≤n; one can build

and

and  This example will be discussed in the section 3.

This example will be discussed in the section 3.

Strings and membranes: A string is a smooth surface Σ possibly with boundary, embedded in  A membrane is a manifold M of higher dimension embedded in some

A membrane is a manifold M of higher dimension embedded in some  We recover here some spaces of the type

We recover here some spaces of the type  which will be also discussed in section 3.

which will be also discussed in section 3.

Branched Configuration Spaces

Dirac branched configurations

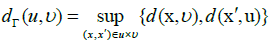

As we can see in section 1.1, finite configurations Γare made of a countable disjoint union. We now fix a metric d on N: The idea of branched configurations is to glue together the components Γn on the generalized diagonal, namely, we define the following distance on Γ:

Definition 3.1: Let

Proposition 3.2: dΓ is a metric on Γ:

Proof: We remark that dΓ is the Hausdorff distance restricted to Γ:

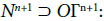

The following proposition traduces the change of topology of Γ into BΓ by cutand paste property:

Proposition 3.3: where the identification is made along the trace on Γn+1 of the dΓ - neighborhoods of

where the identification is made along the trace on Γn+1 of the dΓ - neighborhoods of  in

in

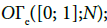

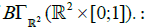

We remark that we can also define a Frolicher structure on BΓ with generating set of functions the set

This structure will be recovered later in this paper.

Examples of topological branched configurations

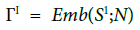

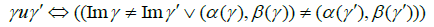

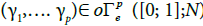

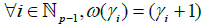

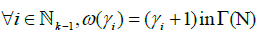

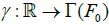

The path space, branched paths and graphs: Let

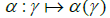

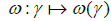

be the space of smooth paths on N: A γ path has a natural orientation, and has a beginning α(γ) and an end ω(γ): We define a compatibility condition

and we remark that the set of piecewise smooth paths on N is a subset of  saying that

saying that is a piecewise smooth path if and only if

is a piecewise smooth path if and only if

This relation, stated from the natural definition of the composition * of the groupoid of paths, is not unique and can be generalized.

Definition 3.4: Let  and let

and let

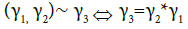

We define the equivalence relation ∼ by

We define the equivalence relation ∼ by

The maps  and

and  extends to \set theorical” maps

extends to \set theorical” maps  and

and  The following is now natural:

The following is now natural:

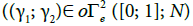

Definition 3.5: A branched path is an element γ of

such that, if

such that, if

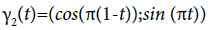

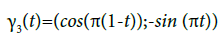

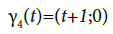

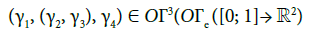

Example: Let us consider the following paths  :

:

Then,

And

This shows that

is a branched path of

Alternate approach to branched paths: branched sections of a fiber bundle.

Let  be a fiber bundle of typical fiber F0:

be a fiber bundle of typical fiber F0:

Here,  Let

Let  be a fiber bundle over M with typical fiber F0: Let

be a fiber bundle over M with typical fiber F0: Let

This is trivially a fiber bundle of basis M with typical fiber

Definition 3.6: A non-section of F is a section of  which cannot be decomposed into n sections of F.

which cannot be decomposed into n sections of F.

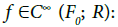

We define also  and also

and also the non sections based of ΓI(F0): We can define the same way BΓM(F) using the branxhed configuration space instead of the configuration space, since the definitions from the set-theoric viewpoint are the same.

the non sections based of ΓI(F0): We can define the same way BΓM(F) using the branxhed configuration space instead of the configuration space, since the definitions from the set-theoric viewpoint are the same.

(Toy) Example: Let us consider the following example:  {up; down}, and

{up; down}, and {{up; {down}; {up; down}}; that models the position of an electron in the 3-dimensional space

{{up; {down}; {up; down}}; that models the position of an electron in the 3-dimensional space  , associated to its spin. When the electron spin cannot be determined (i.e. out of the action of adequate electromagnetic fields), the picture proposed by Schrodinger is to consider that its spin is both up and down (this picture is also called the \Schrodinger cat” when we replace \up” and \down” by \dead” and \alive”).

, associated to its spin. When the electron spin cannot be determined (i.e. out of the action of adequate electromagnetic fields), the picture proposed by Schrodinger is to consider that its spin is both up and down (this picture is also called the \Schrodinger cat” when we replace \up” and \down” by \dead” and \alive”).

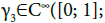

Let us now consider the Frolicher structure described on section 3.1. It is based on the natural diffeology carried by each

and by the set of paths ' P1 that are paths

and by the set of paths ' P1 that are paths  such that

such that

is a smooth path on

is a smooth path on

is a smooth path on

is a smooth path on

Let  Then for any smooth map

Then for any smooth map

where c are the trajectories going to l in 0- equals to the sum of the infinite jet of

where c+ are the trajectories coming from l in 0+:

Remark that the last condition comes from the smoothness required for each map  with

with  This fits with the (fiberwise) frolicher structure of BΓ(F0): Then, a finitely branched section of F is a smooth section of

This fits with the (fiberwise) frolicher structure of BΓ(F0): Then, a finitely branched section of F is a smooth section of  The first examples that come to our mind are the well-known branched processes, and we can wonder some deterministic analogues replacing stochastic processes by dynamical systems. Let us here sketch a toy example extracted from the theory of turbulence:

The first examples that come to our mind are the well-known branched processes, and we can wonder some deterministic analogues replacing stochastic processes by dynamical systems. Let us here sketch a toy example extracted from the theory of turbulence:

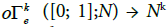

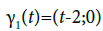

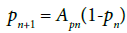

Example: equilibum of mayies population Assuming that Mayies live and die in the same portion of river, the population pn+1 at the year (n+1) is obtained from the population pn at the year n (after normalization procedure) by the formula

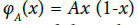

where A ∈ [0; 4] is a constant coming from the environmental data. For A small enough, the fixed point of the so-called “logistic map” is stable, hence the population pn tends to stabilize around this value. But when A is increasing, the fixed point becomes unstable and pn tends to stabilize around 2k multiple values which are the stable fixed points of the map

is stable, hence the population pn tends to stabilize around this value. But when A is increasing, the fixed point becomes unstable and pn tends to stabilize around 2k multiple values which are the stable fixed points of the map  obtained by composition rule.

obtained by composition rule.

Now, assume that we consider a river (or a lake), modelized by an interval (or an open subset of  that we denote by U, where the parameter A is a smooth map U → [0; 4]: The parameter A is a smooth map U → [0; 4] and the cardinality of configuration of equilibrum depends on the value of A:

that we denote by U, where the parameter A is a smooth map U → [0; 4]: The parameter A is a smooth map U → [0; 4] and the cardinality of configuration of equilibrum depends on the value of A:

Non sections in higher dimensions: The example of a lake where mayflies live and die gives us a nice example of branched surface viewed as an element of  The same procedure can be implemented in gluing simplexes, or strings or membranes along their borders to get branched objects, but we prefer to postpone this problem to a work in progress where links with stochastic objects should be performed.

The same procedure can be implemented in gluing simplexes, or strings or membranes along their borders to get branched objects, but we prefer to postpone this problem to a work in progress where links with stochastic objects should be performed.

Measure-Like Configurations: An Example at the Borderline of Branched Configurations and Dynamics on Probability Spaces

Dynamics on probability space is a fast-growing subject and is shown to give rise to branched geodesics [11]. Following the same procedure as for branched topological configurations, we show her how a restricted space fits with particular goals. The goals described he1re are linked with image recognition for the configuration space  above, and to uncompressible fluid dynamics when we equip

above, and to uncompressible fluid dynamics when we equip  with the diffeology P0 of constant volume above. Let C0c be the set of compactly supported

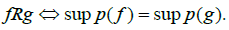

with the diffeology P0 of constant volume above. Let C0c be the set of compactly supported  valued smooth maps on N. We define the relation of equivalence R by:

valued smooth maps on N. We define the relation of equivalence R by:

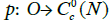

Let us first give the definition of the set of 1-configurations:

Definition 4.1: We set

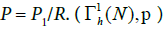

Such a space is not a manifold, but we show that it carries a natural diffeology.  is a topological vector space, and hence carries a natural diffeology P0. We define the following:

is a topological vector space, and hence carries a natural diffeology P0. We define the following:

Definition 4.2: Let  be the set of P0-plots

be the set of P0-plots  such that, for any open subset A with compact closure A of N, for any open subset O′ of O such that

such that, for any open subset A with compact closure A of N, for any open subset O′ of O such that  if

if

the map

is constant on O′, where Vol is the Riemannian volume.

This technical condition ensures that the volume of any connected component of the support of p(x) is constant. P1 is obviously a diffeology on  , and we can state

, and we can state

Proposition 4.3: Let  is a diffeological space.

is a diffeological space.

The proof is a straightforward application of Definition 4.12. It seems difficult to give this space a structure of Frölicher space, or even a natural topology except the topology of vague convergence of measures, which is not the topology induced by the diffeology we have defined. As a consequence, we can only state that the welldefined configuration spaces Γ and ΓI are diffeological spaces. The technical conditions of Definition 4.2 ensures that volume preserving is a consequence of smoothness with respect to P1; and hence is particularily designed for (viscous) uncompressible fluid dynamics. A 1-confiuguration can have many connected components, and therefore branching effects are included in the definition of 1-configurations. One could understand n-configurations as the presence of n (non mixing) fluids.

Appendix: Preliminaries on Differentiable Structures

The objects of the category of -finite or infinite- dimensional smooth manifolds is made of topological spaces M equipped with a collection of charts called maximal atlas that enables one to make differentiable calculus. But there are some examples where a differential calculus is needed whereas no atlas can be defined. To circumvent this problem, several authors have independently developped some ways to define differentiation without defining charts. We use here three of them. The first one is due to Souriau [12], the second one is due to Sikorski, and the third one is a setting closer to the setting of differentiable manifolds is due to Frölicher (see e.g. Cherenack P et al. [13] for an introduction on these two last notions). In this section, we review some basics on these three notions.

Souriau’s Diffeological Spaces, Sikorski’s Differentiable Spaces, Frolicher Spaces

Definition 4.4: Let X be a set.

A plot of dimension p (or p-plot) on X is a map from an open subset  to X.

to X.

A diffeology on X is a set P of plots on X such that, for all pN, - any constant map  is in P;

is in P;

Let I be an arbitrary set; let  be a family of maps that extend to a map

be a family of maps that extend to a map  then

then  (chain rule) Let f∈P, defined on

(chain rule) Let f∈P, defined on  . Let

. Let  an open subset of Rq and g a smooth map (in the usual sense) from O′ to O. Then,

an open subset of Rq and g a smooth map (in the usual sense) from O′ to O. Then,

If P is a diffeology X, (X;P) is called diffeological space. Let (X;P) et (X′;P′) be two diffeological spaces, a map f : X → X′ is differentiable (=smooth) if and only if f(P) ⊂ P’.

Remark: Notice that any diffeological space (X,P) can be endowed with the weaker topology such that all the maps that are in P are continuous. But we prefer to mention this only for memory as well as other questions that are not closely related to our construction, and stay closer to the goals of this paper. Let us now define the Sikorski’s differential spaces. Let X be a Haussdorf topological space.

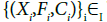

Definition 4.5: A (Sikorski’s) differential space is a pair (X;F) where F is a family of functions  such that

such that

the topology of X is the initial topology with respect to F

- for any n ∈ N, for any smooth function  , for any

, for any

Let (X;F) et (X′;F′) be two differential spaces, a map f: X→ X′ is differentiable (=smooth) if and only if

We now introduce Frölicher spaces.

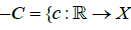

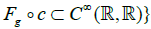

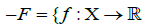

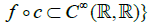

Definition 4.6: A Frölicher space is a triple (X;F; C) such that - C is a set of paths

- A function  is in F if and only if for any

is in F if and only if for any

- A path  is in C (i.e. is a contour) if and only if for any

is in C (i.e. is a contour) if and only if for any  .

.

Let (X;F;C) et (X′;F′;C′) be two Frölicher spaces, a map f : X → X′ is differentiable (=smooth) if and only if

Any family of maps Fg from X to  generate a Frolicher structure (X;F; C), setting [14]:

generate a Frolicher structure (X;F; C), setting [14]:

Such that

Such that

Such that

Such that

One easily see that  This notion will be useful in the sequel to describe in a simple way a Frolicher structure.

This notion will be useful in the sequel to describe in a simple way a Frolicher structure.

A Frölicher space, as a differential space, carries a natural topology, which is the pull-back topology of  via F. In the case of a finite dimensional differentiable manifold, the underlying topology of the Frölicher structure is the same as the manifold topology. In the infinite dimensional case, these two topologies differ very often.

via F. In the case of a finite dimensional differentiable manifold, the underlying topology of the Frölicher structure is the same as the manifold topology. In the infinite dimensional case, these two topologies differ very often.

In the three previous settings, we call X a differentiable space, omitting the structure considered. Notice that, in the three previous settings, the sets of differentiable maps between two differentiable spaces satisfy the chain rule. Let us now compare these three settings: One can see (see e.g. [13]) that we have the following, given at each step by forgetful functors:

smooth manifold ⇒ Frölicher space ⇒ Sikorski differential space

Moreover, one remarks easily from the definitions that, if f is a map from a Frölicher space X to a Frölicher space X′, f is smooth in the sense of Frölicher if and only if it is smooth in the sense of Sikorski.

One can remark, if X is a Frölicher space, we define a natural diffeology on X by Magnot [15]:

p-paramatrization on

p-paramatrization on (in the usual sense) }.

(in the usual sense) }.

With this construction, we get also a natural diffeology when X is a Frölicher space. In this case, one can easily show the following:

Proposition 4.7: Let (X;F;C) and (X′;F′;C′) be two Frölicher spaces. A map f : X → X′ is smooth in the sense of Frölicher if and only if it is smooth for the underlying diffeologies [15].

Thus, we can also state:

smooth manifold ⇒ Frölicher space ⇒ Diffeological space

Cartesian Products

The category of Sikorski differential spaces is not cartesianly closed, see e.g. [13]. This is why we prefer to avoid the questions related to cartesian products on differential spaces in this text, and focus on Frölicher and diffeological spaces, since the cartesian product is a tool essential for the definition of configuration spaces.

In the case of diffeological spaces, we have the following [12,16-19]:

Proposition 4.8: Let (X;P) and (X′;P′) be two diffeological spaces. We call product diffeology on XxX′ the diffeology P x P′ made of plots g: O → XxX′ that decompose as g = f x f ′, where f : O → X ∈ P and f ′: O → X′ ∈ P′.

Then, in the case of a Frölicher space, we derive very easily, compare with e.g. Kriegl A et al. [14]:

Proposition 4.9: Let (X;F;C) and (X′;F′;C′) be two Frölicher spaces, with natural diffeologies P and P′ . There is a natural structure of Frölicher space on XxX′which contours C x C′ are the 1-plots of P x P′.

We can even state the following results in the case of infinite products.

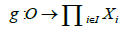

Proposition 4.10: Let I be an infinite set of indexes, that can be uncoutable.

(adapted from [21] ) Let  be a family of diffeological spaces indexed by I. We call product diffeology on

be a family of diffeological spaces indexed by I. We call product diffeology on  the diffeology

the diffeology  made of plots

made of plots that decompose as

that decompose as

where  This is the biggest diffeology for which the natural projections are smooth.

This is the biggest diffeology for which the natural projections are smooth.

Let  be a family of Frolicher spaces indexed by I, with natural diffeologies Pi. There is a natural structure of Frölicher space

be a family of Frolicher spaces indexed by I, with natural diffeologies Pi. There is a natural structure of Frölicher space

which contours  are the 1-plots of

are the 1-plots of A generating set of functions for this Frölicher space is the set of maps of the type:

A generating set of functions for this Frölicher space is the set of maps of the type:

where J is a finite subset of I and φ is a linear map

Proof: By definition, following [12,20],  is the biggest diffeology for which natural projections are smooth. Let g: O→ Xi be a plot.

is the biggest diffeology for which natural projections are smooth. Let g: O→ Xi be a plot.

where pi is the natural projection onto Xi , which gets the result.

With the previous point and Proposition 4.7, we get the family of contours of the product Frölicher space.

Push-Forward, Quotient and Trace

We give here only the results that will be used in the sequel.

Proposition 4.11: Let (X, P) be a diffeological space, and let X′ be a set. Let f : X → X′ be a surjective map. Then, the set [12,21].

f(P) = {u such that u restricts to some maps of the type f o p; p ∈ P} is a diffeology on X′, called the push-forward diffeology on X′ by f .

We have now the tools needed to describe the diffeology on a quotient:

Proposition 4.12: Let (X, P) b a diffeological space and R an equivalence relation on X. Then, there is a natural diffeology on X/R, noted by P/R, defined as the push-forward diffeology on X/R by the quotient projection X → X/R.

Given a subset X0 ⊂ X, where X is a Frolicher space or a diffeological space, we can define on trace structure on X0, induced by X.

If X is equipped with a diffeology P, we can define a diffeology Po on X0 setting

P0 = { p ∈ P such that the image of p is a subset of X0 }.

If (X, F, C) is a Frolicher space, we take as a generating set of maps Fg on X0 the restrictions of the maps f ∈ F. In that case, the contours (resp. the induced diffeology) on X0 are the contours (resp. the plots) on X which image is a subset of X0.

References

- Fadell ER, Husseini SY (2012) Geometry and topology of configuration spaces. Springer Science & Business Media, USA.

- Ismagilov RS (1996) Representations of infinite-dimensional groups. American Mathematical Soc.

- Finkelshtein D, Kondratiev Y, Kutoviy O (2010) Vlasov scaling for stochastic dynamics of continuous systems. J Stat Phys 141: 158-78.

- Finkelshtein D, Kondratiev Y, Kutoviy O (2012) Semigroup approach to birth-and-death stochastic dynamics in continuum. J Funct Anal 262: 1274-1308.

- Finkelshtein D, Kondratiev Y, Kozitsky Y, Kutoviy O (2011) Markov evolution of continuum particle systems with dispersion and competition.

- Finkelshtein D, Kondratiev Y, Kutoviy O (2013) Establishment and fecundity in spatial ecological models: statistical approach and kinetic equations. Infinite Dimensional Analysis, Quantum Probability and Related Topics 16: 1350014.

- Albeverio S, Daletskii A, Lytvynov E (2001) De Rham cohomology of configuration spaces with Poisson measure. J Funct Anal 185: 240-273.

- Hilborn R (2012) Chaos an non linear dynamics, Oxford university Press UK.

- Hagedorn D, Kondratiev Y, Pasurek T, Röckner M (2013) Gibbs states over the cone of discrete measures. J Funct Anal 264: 2550-2583.

- Hughes T, Marsden JE (1983) Mathematical foundations of elasticity Prentice-Hall Civil Engineering and Engineering Mechanics Series. Englewood Clis, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, USA.

- Ohta SI (2014) Examples of spaces with branching geodesics satisfying the curvatureâ€Âdimension condition. Bull Lond Math Soc 46: 19-25.

- Souriau JM (1986) Un algorithme générateur de structures quantiques.

- Cherenack P, Ntumba P (2001) Spaces with differential structure and an application to cosmology. Demonstr Math 34: 161-180.

- Kriegl A, Michor PW (1997) The convenient setting of global analysis. American Mathematical Soc, USA.

- Magnot JP (2008) Difféologie du fibré d’Holonomie en dimension infinite. Math Rep Can Roy Math Soc 28: 121-128.

- Donato P (1984) Revetements de groupes differentiels These de doctorat detat. Universite de Provence, Marseille, UK.

- Frölicher A, Kriegl A (1988) Linear spaces and differentiation theory, John Wiley & Sons Inc, USA.

- Iglesias P (1987) Connexions et diffeologie Aspects dynamiques et topologiques des groupes infinis de transformation de la mecanique Travaux en cours 25: 61-78.

- Leslie J (2003) On a diffeological group realization of certain generalized symmetrizable Kac-Moody Lie algebras. J Lie Theor 13: 427-442.

- Lesne A (1996) Méthodes de renormalisation. Phénomènes critiques, chaos, structures fractales, Eyrolles, Paris, UK.

- Magnot JP (2013) Ambrose–Singer Theorem on Diffeological Bundles and Complete Integrability of the Kp Equation. Int J Geom Methods Mod Phys 10: 1350043.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi