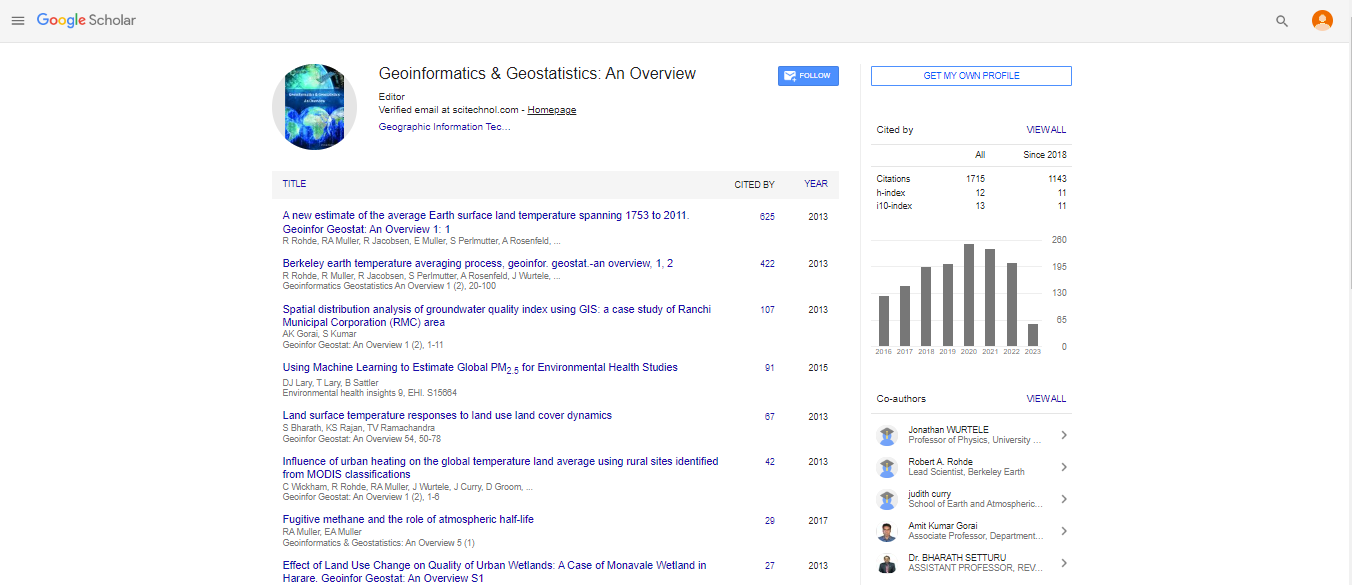

Research Article, Geoinfor Geostat An Overview Vol: 13 Issue: 4

Flood Risk Monitoring around Part of the Niger Delta Basin of Nigeria

Ahmadu AA1*, Dodo JD2, Ojigi ML2

1Department of Geomatics, Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria

2Department of Space Geodesy and Systems Division, Centre for Geodesy and Geodynamics, Toro, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Ahmadu AA

Department of Geomatics, Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria

E-mail: aliahmaduabubakarmsc@gmail.com

Received date: 12 August, 2024, Manuscript No. GIGS-24-145217;

Editor assigned date: 15 August 2024, PreQC No. GIGS-24-145217 (PQ);

Reviewed date: 29 August, 2024, QC No. GIGS-24-145217;

Revised date: 06 August, 2025, Manuscript No. GIGS-24-145217 (R);

Published date: 13 August, 2025, DOI: 10.4172/2327-4581.1000442

Citation: Ahmadu AA, Dodo JD, Ojigi ML (2025) Flood Risk Monitoring around Part of the Niger Delta Basin of Nigeria. Geoinfor Geostat: An Overview 13:4.

Abstract

The influence of environmental geo-hazard events on the society are numerous and are seriously affected by the extent of flood which is exacerbated by climate change variables. This research is tailored towards investigating the dynamics of frequently occurring natural flood disaster. The recently launched Sentinel-1 SAR satellite constellation were adopted for temporal feature extraction and extent assessments over the study area. Methodology adopted involves Binarization (Thresholding) techniques, suitable pixel intensity through Band Maths to calculate and extract water accumulation with-in the Area of Interest (AOI). Result obtained shows that, number of scenes has no influenced on the expected outcome with a gradual increase in flood geo-hazard from September, 2017 (10.49345%) to May, 2018 (12.6057%) and a slight drop in May 2019 (11.47714%). Flood events persist a gradual progressive increase over time with that of October 2022 as high as (12.29319%). It was observed that May, 2018 have the highest percentage of water shade area (12.6057%) with the highest percentage of flood geo-hazard, then October, 2020 (12.29319%), then May, 2019 (11.47714%) and September, 2017 (10.49345%). Rate of water accumulation over the AOI was predicted with an extension to October, 2022. It was evident that flood event is a gradually accumulated and continuous geo-hazard event. Being a continuous phenomenon, over a period of time, it however consumes the solid part of the earth surface made for human activity such as farming and dwelling places. It could be seen that flood rate is not constant because other drivers could also contribute immensely towards increasing flood geo-hazard. The findings suggest a continuous monitoring so as to have a more reliable and current information on geo-hazard phenomenon.

Keywords: Binarization, Band maths, SLC to GRDH, Water mask, Water accuracy, Flood geo-hazard, Rate of water accumulation

Keywords

Binarization; Band maths; SLC to GRDH; Water mask; Water accuracy; Flood geo-hazard; Rate of water accumulation

Introduction

Influence of climate change has been a major thread on associated environment and the society at large leading to all categories of geohazard events in so many ways, approaches and perspectives. Amongst other threads, the intensity of hydrological cycle is leading to more and more extreme drought and precipitation events within and around the environment, society and eventually an increase in the frequency and extent of flood events as a result of water overflowing it banks [1]. As it is the most frequently occurring natural geohazard events, insights into their occurrence and dynamics will be of innermost importance for an effective disaster management as well as for the calibration and validation of flood prediction models, and the optimization of spatial planning [2]. However, it won’t be out of place to appreciate the effort made in providing a systematic, synoptic and timely observation spaceborne remote sensing systems which have become the main source of data for large scale flood events.

As observed, optical sensors are hampered by cloud cover, which is often persistent during flood events [3], which make reliable measurement on the spatial occurrence of historical flood events obviously difficult [4]. Flooding is a global phenomenon, underlined by a range of source mechanisms, and widely considered as the most common natural hazard [5]. Dartmouth Flood Observatory (DFO) made effort to collate and map inundation events as in Figure 1, showing flood occurrence totaling 3,129 since 2000. Given the global nature of flooding, sufficient in situ monitoring is considered geographically impracticable and likely to be expensive, whilst nominally providing point measurements that have questionable use for understanding the dynamics of such an event [6]. Hydrodynamic models were developed for most types of flooding with certain simulations which output flood extent, depth and velocity information [7]. It was made clear that, there are natural and epistemic uncertainties with the development of hydrodynamic models which hamper and reduce confidence in their outputs [8].

Figure 1: Centroid locations and impacted regions of floods event between 2000 and 2018 (n=3129) recorded in DFO database.

The records suggest there were over 390,000 fatalities from flooding during the period, with approximately 350 million people displaced [9]. Urbanization and the replacement of natural land cover with impenetrable surfaces alter the storage and runoff properties by reducing infiltration and increasing surface runoff [10]. Both mechanisms result in water moving faster into the river network, either overland flow or via man-made culverts and sewer systems, which subsequently increases the peak flows whilst reducing the lag time [11]. Flood risk can be categorically made up of three components;

- The probability and characteristics of the flood event,

- The exposure of population and assets to the hazard, and

- The extent on vulnerable community and its ability to cope with the impacts during and after the event [12].

This research is aim at investigating the dynamics of frequently occurring natural flood disaster around part of the Niger Delta basin of Nigeria base on the recently launched Sentinel-1 SAR satellite constellation for temporal feature extraction and extent assessment.

ESA Copernicus programme and the sentinels mission

European Commission (EC) and the European Space Agency (ESA) started the Copernicus programme as a natural successor to the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) programme in 2014 [13]. Earth observation satellites provide efficient and suitable measurement for monitoring a wide variety of environmental variables. Remote sensing imagery has been used towards monitoring surface water extent [14], soil moisture, wetlands and snow cover [15]. Recently launch satellites actually increases the quantity and quality of available data, improving the potential of monitoring geohazard dynamic, environmental variables from space with the European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus programme, including the Sentinel-1 SAR satellite constellation, which provides global imagery every 6-12 days at no cost to the end user [16]. Additionally, satellite data has been used for post-event damage assessments and has helped inform flood risk mitigation and adaptation strategies [17].

Study area

The study area is a part of Nigeria which form boundary to the south with the Atlantic Ocean (coastal water body), East with Cameron Republic, North with Niger Republic and West with Benin Republic. The study area is bounded between the following geographic location (5°E to 8°E) of the Meridian and (4°N to 8.75°N) of the Equator (Figure 2). The study area is located around the mangrove forest and the salt water swamp region of Nigeria. The climate has a luxuriant rainfall all through the year with it dry season not more than one moth of the year (December to January) (geographical alliance of lowa on 14 April 2009).

Figure 2: Map part of Nigeria showing the study area.

Materials and Method

The research encompasses three major components that would aid in the understanding of flood risk monitoring around part of the Niger delta basin of Nigeria. They involve understanding the characteristics features of the study area, the suitable and available dataset and the analysis approach. It is clear that, understanding these three components would guide the research toward archiving the aim of the study. The research approach includes processing of SAR sentinel-1 image scenes for waterlog extraction, temporal feature extraction and extent assessments. Spatial information derived from the processed data were further integrated to assess the extent of water inundation over the study period and area.

Raw data used for this study are sentinel-1 Single Look Complex (SLC), interferometric wide swath (IW) between 2016 and 2019 at an interval of three months (3) each year and GRDH, IW for 2022 as shown in Table 1.

| S/N | Dataset | Source | Purpose | |||||

| 1 | C-Band SLC wide-swath (IW) Sentinal-1A and B | Both descending and ascending satellite passes at https://nisar.jpl.nasa.gov of NASA-ISRO SAR Mission (NISAR) | Used to study the backscattering coefficient of the surface water and phase of the radar sensor over the same scene | |||||

| Satellite | Time of operation and launch | Freq. band | Polarization | Cycle and days | Altitude (km) | Look angle, deg. | Swath width IW (km) | Resolution (m) |

| Sentinel-1A and 1B | 2014 and 2015 | C | Dual | 6-12 | 693 | 20-45 | 400 | 2 |

Table 1: Data set characterastics.

Data acquisition

Data were acquired over the study area and period (2016 to 2019 and 2022) were based on some features such as; size, processing, climate and weather variables. Data were acquired at an interval of three months for each year based on the seosonal behaviour (January, May and September). The acquisition considered the peak of river capture and the lowest level of river capture since most of the water source is rainfall from other part of the country and that of the study area.

Processing approach

The research goal can be determined through the analysis and processing approach using desired data set. There are several approaches and software to be adopted for research of this nature. However, this research adopted the open-source free software known as Sentinel Application Tool Box (SNAP) through the following methodology approach as show in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Flood event approach.

Pre-processing

The first step of flood mapping analysis with SNAP is preprocessing. It starts with slice assembly of sentinel-1 Interferometric Wide (IW) swath mode which is capable of operating up to 25 minutes. Expanding the IW swath into extra wide swath (EW) mode operating up to 60 minutes required the slice assembly of the image scene so as to have a concatenated horizontal exaggeration covering a wider ground area.

Orbit file application: The precise orbit state vector was applied to improve the geocoding of the product so as to have an accurate satellite positioning, timing and velocity. It was automatically applied in the processing software, sentinel application tool box (SNAP).

Sentinel-1 SLC to GRD: Data used for this study are Single Look Complex (SLC) which does not possess the amplitude band but possess the intensity and the complex band. The study is most sensitive to the amplitude band, as such the SLC product is converted to a similar product, Ground Range Detection High Resolution (GRDH) product. The processes involved are;

- Thermal noise removal

- Calibration

- Deburst and merge of TOPS data

- Multilooking

- Speckle Filtering

- Slant Range to Ground Range Conversion (SRGR)

- Scaling to 16 bits

- Updating metadata.

The bursts in all sub-swaths are seamlessly merged to form a single, contiguous, ground range, detected image. The inherent salt and pepper like texture (speckles) of SAR image which degrade it quality and make interpretation of features difficult were taking care of by adopting a suitable model developed by Lee during speckle filtering operation with a window size of 7 by 7 Lee and Pottier.

Terrain correction: Images not directly at the nadir location will experience certain magnitude of distortion. This approach compensates for these distortions so that the geometric representation of the image will be as close as possible to the real-world representation. Figure 4 outline the geometry of topographical distortions. Point B with an elevation h above the ellipsoid is image at position in SAR image, though its real position is Bȼȼ. The offset Dr between Bȼ and Bȼȼ exhibits the effect of topographic distortions.

Figure 4: Doppler terrain effect.

Area of Interest (AOI)

Since the image scene is wide covering far beyond the study area at a very large-scale making feature identification difficult, it calls for a concentration on the Area of Interest (AOI). Sub setting is adopted to clip the image to the region of interest at a certain geodetic coordinate interval (three months each year (Jan; May and Sept)).

Binarization (Thresholding)

Creating water mask region is very crucial to actually delineate the extent of flood event. Water regions have a low back scattered coefficient than non-water regions because they create a smooth surface where the SAR signal is refracted according to Snell’s law which makes it act as a spectral reflectance. Figure 5 with image A (Sigma band 0 scene) and B (Sigma band 0 scene in decibel (db)). The image B gives a sharp distinction between water body pixel and that of other features. The bell curve on the lower left side of the image scene B which have two spikes of the graph showing the intensity values for non-water pixels and the lower spike of the bell curve is for water pixel.

Figure 5: Pixel intesity values of sigma 0 A and B.

Based on this influence of scene A and B, the image is classified as water and non-water area by setting a threshold to create both classes through an approach known as binarization. Binarization is control and also depends on pixel values extracted from the image histogram and statistics. The image scene is converted to a decibel unit which enhance the pixel values thresholding and give a better separability in terms of pixel information with an improved speckle appearance. Polygon layer was used on the image scene to extract the water pixel intensity. Figure 6 shows the position of the polygon layer and the intensity values at the top left side of the figure. The suitable intensity pixel value for water mask is extrapolated from the bell curve at the lower left side of the figure.

Figure 6: Polygon layer intensity values used for water masking.

The lower pixel values correspond to water body whereas the higher values from the bell curve histogram corresponds to other features within the scene. Having obtained a suitable pixel intensity, the study used a Band Maths as another approach to calculate and extract only water bodies within the image scene as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Water mask of the study area.

Figure 8 outlines the extent of water present with-in the study area. The image scene shows that the study area consists of river channels and water shades. It is indicated by the legend table of different colors indicating the extent of water shade. The region appearing in red are mostly built-up areas with the range of value -6.038 m predicting an expectation of flood event. The range of value shows the extent of water shade within the study area and foot print to flooding.

Figure 8 A, B and C displayed and show the water mask accuracy within the study area. The figure to the left shows the values corresponding to accuracy index interms of total number of pixel present, mean value, sigma, coefficient of variation, threshold percentile and maximun error elipse obtain from the procesed result. The bell curve shows an indication for only water pixel intensity whereas the image in red shows the different thresholding values with P75, P80, P85 and P90 values outline in Figure 8C.

Figure 8: Statistical information of the water mask.

Results and Discussion

Monthly flood water monitoring

Figure 9 displayed the contrasting behavioral relationship between the parameters of flood monitoring over the study area and epoch. Figure 9A is a line plot showing a strong positive correlation between the number of active scenes, water accumulation (%) and the Sigma value of the process result. Figure 9B shows the intensity of accumulated water with regards to the number of scenes at monthly intervals for five years including only one month of October in 2022. It shows that, the least active scenes are in January 2016, then September 2019 with the least accumulated water coverage in percentage. The graph shows that percentage of water accumulation increases gradually from January, May and September for every year except for 2019, with the least amount of water in the month of September. It clearly shows that flood geohazard is gradually increasing from September 2017 (10.49345%) to May 2018 (12.6057%) and a slight drop in May 2019 (11.47714%). It shows that such geohazard event is gradually increasing progressively over time with that of October 2022 as high as (12.29319%). The number of scenes does not have any influence on the percentage of accumulated water but the total pixel as seen in Figure 9C with May 2018 having the maximum pixel of (3385141), then October, 2022 (3301221), May, 2019 (3082078) and September, 2017 (2817917).

Figure 9: Result of monthly flood event.

The result of Figure 10 shows the trend relationship between the median, mean, pixel intensity (db), water accumulation and number of scenes using box plot. Figure 10A shows a high positive correlation between the median, mean and pixel intensity (db) as they all appear to be within the upper quartile of the box plot. Figure 10B shows a negative correlation between the number of scenes and the percentage accumulation of water with in the study area which indicated that, the number of scenes does not have any influence on the percentage of accumulated water. Figure 10C and D, show the flood vulnerability in terms of water shade in percentage over the study period at monthly interval.

Figure 10: Monthly correlation flood monitoring event.

It is evident that May, 2018 has the highest percentage of water shade area (12.6057%) with the highest percentage of flood geohazard events. Then October, 2020 (12.29319%), then May, 2019 (11.47714%) and September, 2017 (10.49345%) as shown in Table 2.

| Period | No. of scene | Total pixel | Mean | Sigma | Variation | Max. error | Water accu. (%) | Land area (%) |

| 2016-01 | 5 | 750211 | -100.502 | 10.3357 | -0.5108 | 0.0737 | 2.79366 | 97.20634 |

| 2016-05 | 8 | 1314663 | -153.224 | 17.3145 | -0.9174 | 0.1403 | 4.895584 | 95.10442 |

| 2016-09 | 8 | 1301034 | -161.013 | 16.778 | -0.8373 | 0.121 | 4.844832 | 95.15517 |

| 2017-01 | 8 | 1975400 | -152.282 | 14.0671 | -0.7005 | 0.1595 | 7.356058 | 92.64394 |

| 2017-05 | 9 | 1774661 | -173.246 | 13.7267 | -0.7036 | 0.1372 | 6.608539 | 93.3914 |

| 2017-09 | 9 | 2817917 | -165.362 | 14.6352 | -0.8976 | 0.244 | 10.49345 | 89.5065 |

| 2018-01 | 8 | 2076873 | -160.503 | 15.5076 | -0.7607 | 0.1389 | 7.733926 | 92.26607 |

| 2018-05 | 12 | 3385141 | -220.223 | 19.7895 | -0.9871 | 0.2227 | 12.6057 | 87.3943 |

| 2018-09 | 9 | 1825972 | -187.846 | 14.668 | -0.7023 | 0.14 | 6.799613 | 93.20039 |

| 2019-01 | 14 | 2369905 | -288.675 | 28.15251 | -1.4351 | 0.22906 | 8.825128 | 91.17487 |

| 2019-05 | 11 | 3082078 | -218.101 | 16.8713 | -0.859 | 0.187 | 11.47714 | 88.5229 |

| 2019-09 | 6 | 878982 | -122.814 | 8.8801 | -0.4367 | 0.1168 | 3.273181 | 96.72682 |

| 2022-10 | 12 | 3301221 | -247.33 | 19.8862 | -0.9718 | 0.2741 | 12.29319 | 87.7068 |

Table 2: Percentage level of water accumulation area to land surface area.

Figure 11 predict the rate of water accumulation over the study period of four (4) years with an extension to October, 2022, with the equation and an R2 of less than one (1) as an indication of flood phenomenon. It shows a steady increase of flood geohazard over the study epoch at monthly intervals. It indicated a wide different with no stable increase associated with certain climatic and environmental factors which accelerate the rate of flood event. Below are maps of flood event over the study area at monthly interval.

Figure 11: Rate of water accumulation/flood event.

Annual flood water accumulation

The result of Figure 12 describes the annual flood water accumulation over the study area and period in relation to flood monitoring.

The result of Figure 12A shows the outcome of the processing approach in terms of maximum error, coefficient of variation and active pixel intensity in relation to water accumulation within the study area over the study period. The range of maximum error incurred is less than 0.5 which shows that all signal outliers that would have affected the pixel intensity and variability have been eliminated to the barest minimum leaving only signals relating to the water body. With these, the flood water accumulation is highly quantified in decibel (db) showing regions with more accumulation within the study area over the study epoch. Figure 12B outlines the quantified intensity (db) with the estimated median value. These show a strong correlation with both having the highest values in the same year. Year 2019 has the highest value, then 2018, with least value in 2022. The least value in 2022 is attributed to the fact that it was only one month’s observation that was considered unlike that of other years which has a combination of three months of observation per year. Figure 12C shows the disparity in total pixel over the study period over the same study area. The study area is the same over the study period, but the total pixels differ because of the difference in flood water accumulation as it contributes to flood vulnerability. The range of annual total pixel in mixed descending order are 2018, 2017, 2019, 2016 and finally 2022. The first four years’ values were for three months, and that of the fifth year is for one month, which is why it has the least value, slightly below 2016, 2019, and 2017. Figure 12D was to investigate if there is a high correlation between water accumulation and number of processed scenes. From the box plot, it shows a very weak correlation, meaning that, the number of scenes is not a factor to the concentrated intensity of flood water accumulation over the study area and period. Meaning that, the number of scenes have no influence on the percentage water accumulation. Figure 12E shows the rate of flooded water accumulation of the study area and period. It is clear that, 2018, has the highest water accumulation rate, then 2017, 2019, 2016 and finally one month of 2022. Year 2022, is slightly below the previous years. Meaning that year 2022, would have been the highest if three months were considered or multiply the value of one month by a factor of 2.5 (2.5 × 12.29=30.725%), that is slightly above 2018 by three percent (3%).

Figure 12: Result of annual flood event.

The annual flooded water accumulation rate in percentage is described in Figure 13. The two curves on the chart are for landed area with no flood event and that with flooded water accumulation within the study area over the study epoch. The curve in blue color represents areas with flood event having the least value of flood accumulation in 2016 and the highest in 2022 after being forecasted. The forecast was conducted using the curve slope rate. However, the slope rate is not uniform, therefore the mean value was adopted as (2.76025%) increase over three years between 2019 to 2022. This value was adopted because the flood event displays a steady increase from 2016 to 2018 and slight depreciation in 2019. The prediction is based on the assumption that all contributing factors remain constant with regards to the mathematical variables used for the prediction. However, it is recommended that all contributing factors such as slope, climate and weather parameters, anthropogenic activities be considered for proper flood prediction model and validation.

Figure 13: Rate of flood event to land area linear forecast.

Table 3 shows the percentage relationship of water accumulation to bare land within the study area over the study period in relation to other parameter obtained from the processing carried out with sentinel application toolbox (SNAP) version 8.0 updated (Table 4).

| Year | Water accu. (%) | Slope rate (%) |

| 2016 | 12.53408 | - |

| 2016-2017 | 24.45805 | 11.924 |

| 2017-2018 | 27.13924 | 2.681 |

| 2018-2019 | 23.57545 | -3.564 |

| Mean value | 2.76025 |

Table 3: Linear flood rate forecast.

| Years | No. of scene | pixel intensity | pixel intensity (db) | Total pixel | Mean | Sigma | Median | Variation | Max. error | Water accu. (%) | Land area (%) |

| 2016 | 21 | 0.32993 | -407.34 | 3365908 | -414.74 | 44.4284 | -420.32 | -2.2655 | 0.335 | 12.53408 | 87.46592 |

| 2017 | 26 | 0.35648 | -500.23 | 6567978 | -490.89 | 42.429 | -498.46 | -2.3017 | 0.5407 | 24.45805 | 75.54195 |

| 2018 | 29 | 0.28184 | -566.63 | 7287986 | -568.57 | 49.9651 | -574.47 | -2.4501 | 0.5016 | 27.13924 | 72.86076 |

| 2019 | 31 | 0.31236 | -632.81 | 6330965 | -629.59 | 53.9039 | -632.06 | -2.7308 | 0.53286 | 23.57545 | 76.42455 |

| 2022 | 12 | 0.10319 | -284.08 | 3301221 | -247.33 | 19.8862 | -245.36 | -0.9718 | 0.2741 | 30.725 | 69.275 |

Table 4: Annual percentage level of water accumulation to land surface area.

Map of flood events from 2016 to 2019 were for three months’ interval (January, May and September) for days with data set at a twelve (12) repeat pass of sentinel -1 over the study area and period and part of 2022 for the month of October. They clearly show the concentration of water shade region within the study area, with year 2022 having the least concentration, followed by year 2016, then year 2019, then year 2017 and finally year 2018 having the highest concentration. The higher the concentration, the more prominent and severe to flood geo-hazard over the entire study area. The maps also show rapid rate of increase in flood event if nothing is done as a control measure, especially between year 2017 and year 2018. It proves that once there is an occurrence of flood event in an area with no measure put in place for such occurrence, it will continue to repeat itself covering vital part of the earth surface causing more havoc from year to year (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Annual flood water accumulation monitoring.

Conclusion

The results of the study obviously indicate that flood events are a gradually accumulated and continuous geo-hazard. Being a continuous phenomenon, over a period of time, it however consumes the solid part of the earth surface where most human activity such as farming and dwelling place. It could be seen that the flood rate is not constant, which means that other activities could also play a major role towards increasing flood event. These is as a result of the difference between year 2016-year 2017 and year 2018-year 2019 being a very small magnitude, but that of year 2017-year 2018 being very wide. These could be attributed to the influence of other factors such as rainfall, subsidence, sea level rise and human activities. In conclusion, it calls for a continuous monitoring of the environmental factors so as to have optimum control of such geo-hazard. It will be very paramount to maintain a continuous monitoring so as to give a reliable information of whatever kind of geo-hazard phenomenon is destabilizing the society and inform relevant agencies such as the government (Environmental Protection Agency, National Emergency Management Commission) and other stake holders on measures necessary.

Acknowledgement

The research diligently acknowledges effort of the developers of Sentinel data set obtained from Alaska satellite facilities and Sentinel Application Toolbox (SNAP) software provided by European Space Agency (ESA). The study wishes to acknowledge the center for Geodesy and Geodynamics for the use of their facilities.

References

- Artiola JF, Pepper IL, Brusseau ML (2004) Environmental monitoring and characterization. Academic Press.

- Horton BP, Kopp RE, Garner AJ, Hay CC, Khan NS, et al. (2018) Mapping sea-level change in time, space, and probability. Annu Rev Environ Resour 43: 481-521.

- Bioresita F, Puissant A (2021) Rapid mapping of temporary surface water using Sentinel-1 imagery, case study: Zorn River flooding, Grand-Est, France. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 731, No. 1, p. 012031). IOP Publishing.

- Bovenga F (2020) Special issue “synthetic aperture radar (SAR) techniques and applications”. Sensors 20: 1851.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cazenave A, Cozannet GL (2014) Sea level rise and its coastal impacts. Earth's Future 2: 15-34.

- Clement MA (2020) Flood Extent and Volume Estimation using Multi-Temporal Synthetic Aperture Radar. (Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University).

- Earthdata Search (2019) Greenbelt, MD: Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) Project, Earth Science Projects Division (ESPD), Flight Projects Directorate, Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

- Landuyt L, Van Coillie FM, Vogels B, Dewelde J, Verhoest NE (2021) Towards operational flood monitoring in Flanders using Sentinel-1. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 14: 11004-11018.

- Jong LS, Pottier E (2009) Polarimetric Radar Imaging from Basic to Applications. 1st Edition, Boca Raton, 422.

- Li C, Dash J, Asamoah M, Sheffield J, Dzodzomenyo M, et al. (2022) Increased flooded area and exposure in the White Volta river basin in Western Africa, identified from multi-source remote sensing data. Sci Rep 12: 3701.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinis S, Clandillon S, Plank S, Twele A, Huber C, et al. (2017) ASAPTERRA-Advancing SAR and Optical Methods for Rapid Mapping.

- Matgen P, Martinis S, Wagner W, Freeman V, Zeil P, et al. (2020) Feasibility assessment of an automated, global, satellite-based flood-monitoring product for the Copernicus Emergency Management Service. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Rajakumari S, Muthaiah MAB, Meenambikai M, Sarunjith KJ, Ramesh R (2021) Mapping of water logged areas using SAR images to assess the impact of Tropical Cyclone Gaja in Nagapattinam district, Tamil Nadu using Remote Sensing and GIS. Int J Res Eng Technol 8: 2-12.

- Scheer J, Holm WA (2010) Principles of modern radar. Published by SciTech Publishing, Inc.

- Sadek M, Li X, Mostafa E, Freeshah M, Kamal A, et al. (2020) Lowâ?ÂCost Solutions for Assessment of Flash Flood Impacts Using Sentinelâ?Â1/2 Data Fusion and Hydrologic/Hydraulic Modeling: Wadi Elâ?ÂNatrun Region, Egypt. Adv Civ Eng 2020: 1039309.

- World BG (2016) The Effect of Climate Change on Coastal Erosion in Wset Africa. West African Coastal Areas Management Program.

- Younis M (2015) Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR): Principles and Applications. In 6th ESA Advance Training Course on Land Remote Sensing (No. 82230).

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi