Review Article, J Tourism Res Hospitality Vol: 11 Issue: 9

TOURISTS’ TRAVELLING PATTERNS IN TOURISM MANAGEMENT

Jyotirmaya Satpathy1*, Mohammad Shahidul Islam2, Sebastian Zupok3 and Fariba Azizzadeh4

1Department of Management Studies, University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Tourism Research, Brac University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Department of Management, Islamic Azad University, Piranshahr (Urmia), Iran

4Department of Management, Higher School of Business National Louis University, Nowy Sącz, Poland

*Corresponding Author: Jyotirmaya Satpathy

Department of Management

Studies,

University of Africa,

Nairobi,

Kenya,

Tel: +7260815968;

E-mail: jyotisatpathy@gmail.com

Received date: 22 Jun, 2022, Manuscript No. JTRH-22-67315; Editor assigned date: 24 Jun, 2022, PreQC No. JTRH-22-67315 (PQ); Reviewed date: 08 July, 2022, QC No. JTRH-22-67315; Revised date: 29 August, 2022, Manuscript No. JTRH-22-67315 (R); Published date: 06 September, 2022, DOI: 10.4172/2324-8807.10001003.

Citation: Satpathy J, Islam MS, Zupok S, Azizzadeh F (2022) Tourists Travelling Patterns in Tourism Management. J Tourism Res Hospitality 11:9.

Abstract

By analyzing secondary data publicly accessible, produced and cited on the webs by the British Tourist Authority (BTA) and Tourism Australia (TA), this paper embodies an exploratory empirical study to highlight the role of attractions that influence tourists to visit destinations. Thus, this study qualitatively tests pearce's travel career pattern's juxtaposition with McKercher's tourism product taxonomy by examining tourists' motives from important source markets, such as China, India and France in visiting the United Kingdom and Australia. Findings show that destinations predict themselves differently from source markets based on the tourists' needs and characteristics, even though they are recently moving towards promoting several generic attractions rather than focusing on a few popular attractions.

Keywords: Tourist behavior, Attractions, Motives, Destination attributes, Travel career pattern

Introduction

Over the last couple of decades, tourism scholars and practitioners have shown much interest in the overall system of tourist attractions [1]. For the development of tourist attractions and their management in a destination, many years ago, Leiper asked the stakeholders to contemplate tourist attractions, their components and their operations [2]. Moreover, in recent times, scholars also emphasized the importance of the tourist attractions system in the study of tourism [3]. They showed clear evidence of the use of visitor attractions to develop destinations via engagement with government agencies, academic communities, and engagement with new and existing visitors. Through the ways suggested by scholars, this study has shown interest to explore the tourist attractions system in a couple of destinations and with their four similar source markets.

However, specifically, this exploratory study is designed to understand the theoretical proposition “do attractions attract tourists or simply satisfy needs?” by analyzing qualitative market reports on four source markets (e.g., India, USA, China, and France) from two different destinations (e.g., UK and Australia) to determine if attractions play a different role in ‘attracting tourists’. For this specific purpose, in a qualitative manner, the study has considered first, source market comparison and second, destination comparison by answering two research questions, such as (1) how the UK and Australia are different across India, USA, China, France and (2) how the same destination regards each different source market.

Literature Review

What are tourist attractions? This question has been answered by many as central to the tourism process. However, attractions “are often the reason for visiting a particular destination, providing activities and experiences and a means of collecting the signs of consumption” [4]. Other scholars also considered tourist attractions in adding to diverse perspectives, which are essential in conceptualizing the setting of this study as well; for example, Rojek remarked attractions as “the urge to travel to witness the ‘extraordinary’ or the ‘wonderful’ object seems to be deep in all human cultures” (p.52). Hu and Wall defined tourist attractions as ‘a permanent resource, either natural or human made, which is developed and managed for the primary purpose of attracting visitors’ [5]. The postulation of Pearce and Leiper regarding tourist attractions suggests we consider systematically tourist attractions to develop and revitalize destination management and plan marketing strategy, viz, they viewed that tourism attractions should be discussed systematically, they centralized their works under the umbrella of total tourist attractions system. However, Pearce noted that “A tourist attraction is a named site with a specific human or natural feature which is the focus of visitor and management attention” (p.36), while Leiper mentioned that tourist attractions are “an empirical relationship between a tourist, a sight and a marker-a piece of information about a sight.”

Then again, a recent academic community has made some arguments on the tourist attractions system, which has advanced the features of the tourist attractions system and added to new dynamics. For example, McKercher, McKercher and Koh noticed some challenges in the cause and effect relationship between attractions and visitation since attraction as a term is used by stakeholders to mean different things. They further argued that the term attractions had been applied with a limited vision towards keeping pace with consumer psychograph in the recent digital distribution system and showed loose engineering towards tourists' extrinsic and intrinsic appeal for visiting a destination. Consequently, they raised a logical question, "do attractions attract tourists or simply satisfy needs?" which tends to set tourist attractions system into an effective box for destination management to mediate on and understand tourism products and management, which was not contemplated duly in the past on academic models/frameworks, as such Pearce's travel career pattern model and McKercher's framework of the role of individual attractions in drawing tourists to a destination proposed attraction's hierarchy model.

Nevertheless, challenges noticed by McKercher, McKercher and Koh include, (1) The previous scholars, conceptualization of attractions as single entities with precise spatial or temporal dimensions, which exist in the literature of Leiper, attractions system, (2) Concern with UNWTO’ prescription of attractions, which describes anything can be considered attractions if visitors use them, (3) Attractions as a collective noun “represents agglomerations of single entities into increasingly broad hierarchal categories” that requires the involvement of marketing vision, such as “a six‐tier taxonomy of tourism products” [6,7]. They observed a loophole in the attractions system. Consequently, the above challenges ask McKercher, McKercher, McKercher and Koh to understand how the tourist attractions system toward tourist and their need and appeal evolves. They claimed that destinations might have built attractions to draw visitors. This conventional notion can be primarily true and is based on the push theory of marketing. Still, they argued that people might also travel to have personal needs met rather than to visit specific attractions in a particular destination. The needs of tourism products to an individual can be diverse. McKercher innovated tourism product taxonomy, like all taxonomies. “The tourism product taxonomy begins with the five broad need families of pleasure, personal quest, human endeavour, nature and business. While all touristic consumption occurs at the item level of the taxonomy or in simple terms at specific spatial or temporally based attractions, the taxonomy recognises that the driver of tourism may be found at a higher, more generic level. As such, the importance of an individual attraction may vary depending on the specificity of need”.

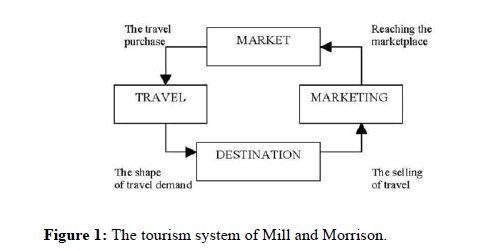

Though scholars in recent years have profoundly contributed to the extant literature on tourist attractions system, the past literature on tourist attractions system has also produced comprehensive insights on tourist attractions system. For example, Mill and Morrison functionally posited tourism attractions in a unique tourism system, evolving into the four key components, market, travel, tourism destination and marketing. Again these components circle together as:

• The travel purchase.

• The shape of travel demand.

• The selling of travel and reaching the marketplace.

Tourism attractions are placed in the tourism destinations quadrant, highlighted as the attractive factors of tourism supply (Figure 1).

However, earlier than Mill and Morrison, literature in the area of attractions pointed out that “tourist attractions as the first power the real energizer of tourism in a region and that without attractions, both inferred and developed, there would be no need for other tourism services.” In Gunn, three zones are traced concerning the spatial layout of an attraction, such as (1) The central nucleus with the core attraction, (2) The ancillary services associated with the attraction and (3) The inviolate belt that separates the core attraction from the commercial aspects of the zone of closure [8]. MacCannell also identified three components that encompass an attraction: a tourist, a sight and a marker. The latter (marker) created the basement of the information, which draw the consumer’s decision to visit the attraction. In terms of past literature, Leiper illustration of the tourist attractions system is prominent. He proposed that the attractions form part of a system and related the product of the attraction more to the motivation of visitors than to the draw of an attraction feature [9]. The paper traced that at least one of the three types of markers, such as generating, contiguous and transit, impacts the tourists to be pushed (an appropriate metaphor) by their motivation towards the places and/ or events where they expect their needs will be satisfied. The motivation depends on information, received from at least one detached marker, matching the individual’s perception of needs and the individual’s felt wants. Traveling towards the nucleus, additional (transit) markers might be noticed and at the nucleus, continuous markers might also play a part in the experience. At least one meaningful marker (if any of those places) is necessary before the three components become connected to form an empirical entity, an attraction system”.

Besides, the findings of McKercher and Lau in the proposition of Leiper are essential, are found that “in destination or contiguous markers are especially important for low order attractions where up to three quarters of visits are influenced by information provided in the destination [10]. Thus, the survival of many lower order attractions depends on knowledge brokers during visits to tourist information centres” [11]. Furthermore, from the extant literature, to understand peoples’ needs or motives or trip decision as drivers of tourism gains the essentials in this study [12]. Understanding the motives of travellers is essential in the analysis of destination competitiveness, which is linked to the capacity of a destination to distribute goods and services, which are to perform superior to other competitors in regards to tourism experience, which are invaluable to tourists [13]. McKercher and Koh pointed out a further challenge lies in defining needs or motives as drivers of tourism, for they too lie along a continuum from the specific to the vague. In some cases, the decision may be driven by a single motive, as is the case of business or visiting friends and relatives travel” [14].

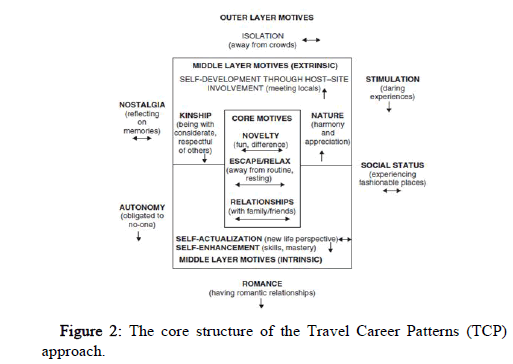

However, McKercher and Koh tend to agree with pearce's most recent travel career pattern model, where pearce showed that travel decisions are influenced by the mix of and relative importance located on core, middle and outer layer motives. Core motives comprise novelty (fun, difference), escape/relax (away from routine, resting), relationships (with family/friends), while middle layer motives include self-actualization (new life perspective), self-enhancement (skills, mastery), last but not least, outer‐layer motives include some exclusive features as social status (experiencing fashionable places), romance (having romantic relationships), nostalgia (reflecting on memories), isolation (away from crowds) and so forth. However, core motives mostly play a distinct role to travel, but the ultimate travel decisions may also tend to come from the travellers middle and outer layer motives (Figure 2) [15].

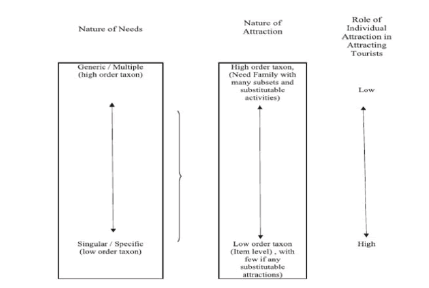

However, McKercher and Koh believe that an attractions/needs relationship framework to understand the role of individual attractions plays the role to draw tourists to a destination. They tested McKercher’s attraction hierarchy model in the boundary of pearce's travel career pattern model as discussed above. It demonstrates the relationship between the number and (relating uniquely) to a particular need and the corresponding number, specificity and alterability or changeability of different attraction sets that can satisfy those needs. The graph also elucidates that if requirements are solely designed and kept specific, then either individual attractions or narrow attraction sets play a vital role in the trip decision (Figure 3).

Case study

To be specific, this study builds on the earlier case of Singapore. A similar method of that case is adopted that is to recapitulate, to explore the proposition “do attractions attract tourists or simply satisfy needs?” along with answering questions mentioned in the introduction. This study utilizes secondary data publicly accessible, produced and cited on the web by the British Tourist Authority (BTA) and Tourism Australia (TA).

Besides, this study also considers secondary data from other sources, e.g., journal articles, online documents. A growing body of scholars believes that employing secondary data is valuable and rigorous to test or examine the influence of a theoretical proposition or framework on a particular discipline [16]. Besides, secondary data are considered for several advantages, such as developing a rich and nuanced understanding of the research area and gathering valuable sources of ideas.

Moreover, existing documentation used by organizations or agencies [17], can also offer comparisons with new research and might uncover unanticipated issues.

It is for these purposes that data and documents used by the BTA, TA, journal articles and concerned websites are assessed in this study to capture the wealth of knowledge and identify the in depth elements of what drive people to visit the UK and Australia; what are the volumes of their demography; what types of activities, attractions they go through, and other issues such as travel pattern, general perceptions they project, how they demonstrate their needs and how destination executives plan to promote their tourism products as best as possible (Table 1).

| • The BTA Report is based on International Passenger Survey by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2016. |

| • The TA Report based on Consumer Demand Project, Tourism Research Australia, and International Visitor Survey 2016, and TripAdvisor, Internal Data, December 2016, and TripAdvisor, Internal Data, December 2016. |

Table 1: Sources of data.

Discussion

India’s market toward the UK and Australia

India market in the UK: India is Britain’s 18th largest source market, with 415,110 visitors in 2016. Among them, 34% came for a holiday and 31% to visit friends and relatives, while 29% visited the UK for business purposes. Over one in four visitors from India are aged 55+, above the all-market average (19%). Indian visitors tend to stay longer than the all-market average visitor, spending 24 nights on average per visit in the UK, compared to just seven across all markets. BTA identifies that Indians who travel to the UK are still very much influenced by visits to friends and relatives. This can explain why over half of the nights spent by Indian visitors in the UK in 2016 were spent for free as a guest at friends or relatives places.

Among Indian visitors, dining in restaurants is the most popular activity (69%), followed by shopping and visiting parks or gardens. Sightseeing famous monuments/buildings too are popular among Indian visitors. Food is an essential element of a trip for an Indian visitor. Indian diets can be different from European diets. They are likely to choose a destination where they know they can find foods that suit their diet, based on their religious beliefs.

Indians perceive Britain as the best place to revisit places of nostalgic importance. BTA identified that the most important reason for choosing Britain as a holiday destination is the wide variety of places to visit, the natural beauty, cultural attractions and the advantages of visiting friends or relatives.

India in the UK is historically linked because the British ruled India for approximately 200 years. Mostly UK curry industry is dominated by South Asians led by Indians. The numbers of British-Indian are pretty high; about 1.4 million include people born in the UK who are of Indian descent and Indian born people who migrated to the UK [18]. This backdrop, as well as the insight of the BTA represent predominant travel motives of Indian travellers such as relationship building with family and friends (pearce’s core motive), nostalgia, experiencing fashionable places as the epitome of social status (pearce’s outer layer motives).

India market in Australia: India was Australia’s ninth largest inbound market for 259,900 visitors’ arrivals in 2016 and stood fifth for visitors’ length of stay, which was an average of 61 nights. 42% of visitors were on a holiday, while 24% and 13% came for visiting friends and relatives and business, respectively. One-third of Indian visitors travelled to Australia as a couple.

The TA showed that most Indian visitors regarded Australia as a destination offering beautiful beaches, family friendly attractions, modern cities with nightlife and a multicultural society with friendly citizens. TA identified the critical thematic appeals and experiences of Indian travellers towards natural beauty aquatic and coastal, and food and wine experiences.

The primary section of visitors planned their trip based on their friends and relatives events or festivals in Australia. Preferred styles of travel include resort and beach holidays. Indian travellers in Australia demonstrated their strong inclination toward nature (pearce’s middle layer motives), escape that allows people to spend quality time with their friends and family and self-actualization (pearce’s intrinsic middle layer motives).

USA market towards the UK and Australia

USA market in the UK: The USA is the UK's second largest visitor source, contributing 4.46 million visitors in 2016. Almost 45% of them (1.6 million) came for a holiday and 25% to visit friends and relatives. USA is unique in several ways, such as 85% of visits from American residents to the UK were made by American nationals, almost 6 out of 10 American holiday visitors are making a repeat visit to Britain, and business visitors are more than two times as likely to be men than women, about 56,000 visits per annum feature time watching football, 66% visitors came with a spouse. Popular activities of Americans included dining in restaurants (74%), shopping (57%) and going to a pub (55%). Moreover, museums and galleries, and castle or historic houses visits were made by almost 60% of leisure visitors. Most Americans are influenced by websites providing, travellers' reviews and word of mouth to travel the UK.

The BTA revealed that cultural attractions and the ease of getting around are solid drivers for American visitors to visit Britain. According to the Travel Career Patterns (TCP) approach of Pearce, visits of Americans capture the different motives comprised of the core, middle and outer layer motives, such as Americans demonstrating their visit for escaping from stress and pressure of daily routine as well as recharging their batteries, reviving social status, engaging in self-actualization.

USA market in Australia: The USA is s fourth-largest source market of Australia, generating 711,400 arrivals in 2016. A majority (43%) came for holidays, 25% for visiting friends and relatives, and 20% for business. Point to note; the leisure travellers are almost averagely 60+ years old, 140,400 (25%). Primarily 61% of repeat visitors account for VFR.

The TA identified quality food and beverage management, unique aquatic and coastal experiences and the opportunity to be into world class nature are vital drivers for Americans to visit Australia. Their travel style shows that leisure activities mainly shadow the purpose of visiting Australia and visiting friends and family.

However, Americans perceive Australia as a destination offering aspirational, iconic landmarks from coastal to outback terrain, modern cities, laidback people and world class beaches. Research indicates that 'the great barrier reef' is an appealing Australian attraction to Americans.

The TA indicates Americans, in general, travel for both escape and relaxation and a sense of achievement. However, bonding with family members and relatives and escapism seem to dominate travel decisions for Australia. The study reveals Australia's wide range of attractions and activities provide Americans with a platform for these needs to be met [19].

China’s market toward the UK and Australia

China market in the UK: The BTA evaluated China as the most valuable market for international tourism expenditure with US $261.1bn spent abroad attracting just 260.432 Chinese travellers in 2016. Some 46% came for a holiday and 22% to visit friends and relatives and 18% for business. The same source of the report noted that Hong Kong and Macao are usually the most visited Chinese travellers. Still, with more of them now venturing further away, the USA, France, Germany, and Australia were the most popular destinations outside of Asia for Chinese visitors in 2016. On the other hand, interestingly, Chinese travellers for education are also increasing; for example, Chinese students make up 42% of the nights in the UK visits and are identified as a critical market for the study of tourism. However, in general, trips of 15+ nights are also quite popular, especially for VFR [20].

The average Chinese visitor is comparatively younger than all other source markets; this accounts for almost 51% during 2014-2016. Remarkably, in the same duration, Chinese visitors comprised almost male 50% and female 50%. In the UK, shopping is the number one activity most Chinese visits feature, followed by visiting parks, gardens, museums and art galleries. They showed much interest in British cultural heritage and contemporary culture, especially in museums, films and symbolic elements such as the Royal Family, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, Harry Potter and Downton Abbey.

The BTA further reported that Hong Kong and Macao welcomed a third of Chinese outbound visits in 2016; Northeast and Southeast Asia accounted for 77%. However, the Chinese middle and upper classes now explore destinations further away than ever before and this trend is set to grow. Chinese travellers of this section perceived the UK as 'fascinating', 'romantic', 'relaxing', and 'spiritual.' However, their travel motives align closely to pearce's middle and outer layer motives. This observation is exceptionally accurate for tourists from the Chinese middle and upper classes with whom overseas travel carries a significant indication of experiencing fashionable places, having romantic relationships, a new life perspective and social and status value.

China market in Australia: Australia has recently introduced ten year multiple entry visas for Chinese nationals, facilitating return visitation from this vital market (TA, 2016h), which was concurrently Australia's second largest inbound market for visitor arrivals of almost 1.20 million and the most significant market for total spend and visitor nights in 2016. Australia saw 55% of Chinese visit the country for a holiday, 19% for VFR, 7% for business and remarkably 118,600 (13%) for education. Of which about 57% are repeat visitors, the significant share of visitors for education is 76%.

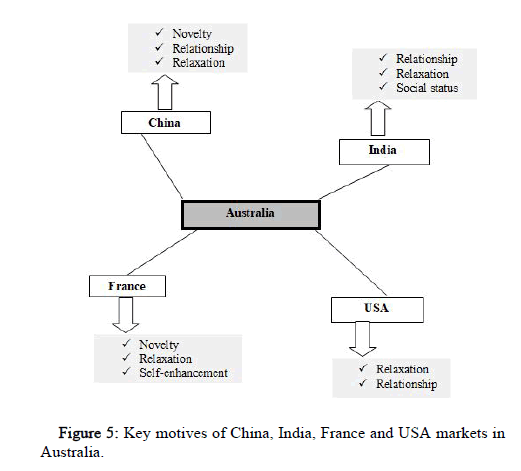

Chinese traveler’s popular iconic activities include enjoying the virgin natural beauty, aquatic and coastal experiences and spectacular coastal scenery, fresh air, vibrant cities and self-drive experiences. 40% of Chinese travelled as a couple. Pearce's core motives, such as novelty, relaxation and bonding relationships with loved ones, to the point, desire to go beyond the surface by creating a story around them were the critical drivers for Chinese in Australia.

France’s market toward the UK and Australia

France market in the UK: France is the UK’s top source market, with 4.06 million visitors in 2016. 42% of all visits to the UK from France were made for holiday purposes, followed by 30% of visits made to visit friends and relatives and 21% for business in 2016. Short trips of 1-3 nights and 4-7 nights are the most popular duration of stay amongst French visitors.41% of French visits were made via the channel tunnel (which links Britain and France) by rail or car, followed by 39% by plane and 21% by ferry.

The most popular activities undertaken by French travellers in Britain include shopping, going to the pub, visiting parks and gardens, visiting museums and art galleries and castles and historic houses and religious buildings. French visitors are framed into relaxed sightseers, curious explorers and active buzz seekers dominated by urban middle class, higher income families, and empty and young independent travellers. More than half of holiday visitors are making a repeat visit to Britain. French showed much interest in contemporary culture, vibrant cities, and sport; they welcomed scenic natural beauty slightly. About 35,000 visitors came to the UK for watching football in 2016.

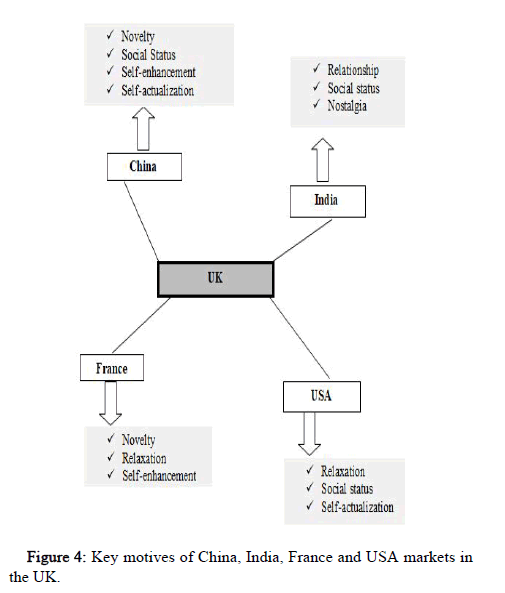

However, precisely French visited the UK to see ‘famous sites’ and immerse themselves in ‘lots of history’ and watch sporting events. Thus, the travel motives of the French can be captured in the feeling of achievement when going to aspirational places and showed a preference for independent travel and short trips by desiring a chaos free and direct experience, in some cases, they want to escape that allows people to spend time for enhancing skills reflected in cultural newness and historical discovery (Figure 4).

France market in Australia: In 2016, France was Australia's 15th largest inbound market for visitor arrivals, a total visitor spends and 12th for visitor nights. French travellers preferred Australia because it preserves travellers' safety and has unique pieces of world class nature, history and heritage. Most French visitors (52%) were young, especially those who came for a holiday. Less than one third of trips are tour groups, with most trips involving semi-independent or fullyindependent travel. Research revealed that 21% of visitors visit Australia from the recommendations of friends and relatives that have been living or had been living there for some spell of duration (Figure 5).

Last not but least, according to the BTA market profile comprehension, specific attractions play a crucial role in drawing visitors from China, France and the UK. In some cases, Indian and USA travellers seem attracted by extrinsic appeal as needs satisfiers. In the case of Australia, markets like the USA, China and France are attracted by mostly intrinsic appeal while accompaniment of extrinsic appeal as needs satisfiers is also identified. Indians appeals seem extrinsic but coated with intrinsic. However, excluding India, travelling abroad seems routine work for travellers from China, the USA and France, or they can be termed trained travellers. Their activities show that popular iconic attractions attract them. Indian travellers tourism activities abroad may imply as to kill two birds with a single stone. Still, the per capita income of India is below 1,800 US $. For Indians, visiting the UK and Australia is quite expensive in the sense of per capita income. The author intuits as attached to South Asian background. Visiting developed countries seems still an ambition for Indians and mostly their travelling fund are backed by their family members/relatives and friends living abroad. Consequently, they seem less attracted by particular attractions, valuably noted, their travel motives are extrinsically influenced. On the other hand, China, the USA and France travel for specific product consumption in the UK and Australia from an intrinsic point of view, which is not ultimately far away from the extrinsic pattern of travelling, especially those who travel for social status and selfenhancement.

Conclusion

The findings of this study have provided a comprehensive indication that people do not travel only for specific attractions, or a destination cannot be posited to draw tourists based on only built attractions. In contrast, tourists motives account multi tiers of needs. In this context, pearce's travel career pattern is applicable to suggest that a relationship exists between or among outer, middle, and core motives. However, this study can be seen through the lens of McKercher's product taxonomy model and pearce's, the most recent travel career model. The products are explicitly available in product taxonomy, such as how the needs of a personal quest, pleasure, human endeavour, and nature captured the source markets. For example, the pleasure need family captures much of French, the USA and Chinese travellers to the level of intensity. At the same time, the Personal Quest Need Family accounts mainly for Indian travellers. However, the Human Endeavour and Nature Need Families attract each source market. In case of considering pearce's most recent travel career model, this study found the travel motives of four source markets, just adding the motive level as evident in the BTA and TA reports, for India: relationship, nostalgia, social status in the UK, relaxation, relationship, social status in Australia, for Chinese: novelty, social status, self-enhancement, self-actualization in the UK and mostly a novelty, relationship, relaxation in Australia, for France: novelty, relaxation, self-enhancement in both the UK and Australia, for the USA: relaxation, self-actualization, social status in the UK and relaxation, relationship in Australia.

However, "do attractions attract tourists or simply satisfy needs?" should not be answered from assumption. The specific answer of this academic proposition enquires justifiable shreds of evidence. This study undergoes different types of tourists with different cultural backgrounds, their attitudes and activities over a destination are also different. Consequently, their needs are not similar in most cases as well. Hence the study findings reveal that tourists travel for both attractions and their needs satisfaction, but interestingly and increasingly, they are closely related and evolve together. The author having a South Asian cultural background understands that his people, in general, do not remain certain about what they would like to choose or what they are going to do in a particular destination; they are curious about what is easy and cheap; is there any other opportunity? (e.g., to live or work or study in the destination).

This attitude shows that they are inquisitive about needs satisfaction. The author contemplates; that instead of "attractions", "appeals" in the quality of "extrinsic" and "intrinsic" can be more suitable action word to understand tourists’ motives of travel, this notion is not different from McKercher's product taxonomy model, Pearce's the core structure of the Travel Career Patterns (TCP) approach, and McKercher's model on the role of individual attractions in drawing tourists to a destination.

To conclude, the study findings endorse that attractions do not exclusively attract tourists, or even exclusively their needs make them driven. There could be some exceptions (attractions could attract some), but the data sources could not support this evidence. However, this study finds a relationship between attractions and needs complementary and harmonized.

References

- Azizzadeh F (2019) Pathology of Tourist Attraction Problems in St. Mary Church of Urmia. J Environ Manag Tour 10:1956-1962.

- Leiper N (1990) Tourist Attraction Systems. Ann Tour Res 17:367-384.

- Mckercher B (2017) Do Attractions Attract Tourists? A Framework to Assess the Importance of Attractions in Driving Demand. Int J Tour Res 19:120-125.

- Richards G (2002) Tourism Attraction Systems: Exploring Cultural Behavior. Ann Tour Res 29:1048-1064.

- Hu W, Wall G (2005) Environmental Management, Environmental Image and the Competitive Tourist Attraction. J Sustain Tour 13:617-635.

- Pearce PL (1991) Analysing Tourist Attractions. J Tour Stud 2:46-55.

- Lew AA (1987) A Framework of Tourist Attraction Research. Ann Tour Res 14:553-575.

- Mckercher B (2016) Towards a Taxonomy of Tourism Products. Tour Manage 54:196-208.

- Leask A (2010) Progress in Visitor Attraction Research: Towards More Effective Management. Tour Manage 31:155-166.

- Garrod B, Fyall A, Leask A, Reid E (2012) Engaging Residents as Stakeholders of the Visitor Attraction. Tour Manage 33:1159-1173.

- Mckercher B, Lau G (2007) Understanding the Movements of Tourists in A Destination: Testing the Importance of Markers in the Tourist Attraction System. Asian J Tour Hosp Res 1:39–53.

- Wong CU, Mckercher B (2011) Tourist Information Center Staff as Knowledge Brokers: The Case of Macau. Ann Tour Res 38:481-498.

- Azizzadeh F, Shirvani A, Sarihi Sfestani R (2014) Ranking The Motivational Factors Of Teachers In Urmia Using SAW Method (2011). Int J Inf Bus Manage 6:198-206.

- Enright MJ, Newton J (2004) Tourism Destination Competitiveness: A Quantitative Approach. Tour Manage 25:777-788.

- Pearce PL, Lee UI (2005). Developing the Travel Career Approach to Tourist Motivation. J Travel Res 43:226-237.

- Johnston MP (2017) Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come. Qual Quan Meth libr 3:619-626.

- Zupok S (2018) Value for the Customer and the Goals of the Organization. Econ Organ Enterp 53:77-88.

- King R, Sondhi G (2018) International Student Migration: A Comparison of UK and Indian Students’ Motivations for Studying Abroad. Glob Soc Educ 16:176-191.

- Chomać-Pierzecka E, Kokiel A, Rogozińska-Mitrut J, Sobczak A, Soboń D, et al. (2022) Analysis and Evaluation of the Photovoltaic Market in Poland and the Baltic States. Energies 15:669.

- Reitsamer BF, Brunner-Sperdin A (2017) Tourist Destination Perception and Well-Being: What Makes A Destination Attractive?. J Vacat Mark 23:55-72.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi